The China Diviner

China didn't ease like the US in 2020, tightened in 2021, and yet leverage is still rising. In the short term, there's unlikely to be a change without more policy support for households. With Beijing against welfarism, that seems unlikely, which suggests a structural outlook of lower interest rates.

Less easing, more deleveraging, but debt still rising

China has made a big deal of sensibleness, that it is an oasis of sanity in a US-led world where economic policy since the onset of the pandemic has gone crazy. That attitude is epitomized by Guo Shuqing, head of the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission, in remarks made in 2020:

...we are all aware that this is not the Last Supper, so room must be left for the future. Many countries have rolled out fiscal and financial incentives of unprecedented scale and intensity.....As we know, quite a few countries and regions are considering additional incentives. It is recommended that everyone think twice before action and reserve some policy space for the future. China values very much the normal monetary and fiscal policies we are practicing now. We will not flood the economy with liquidity, still less employ deficit monetization or negative interest rates.

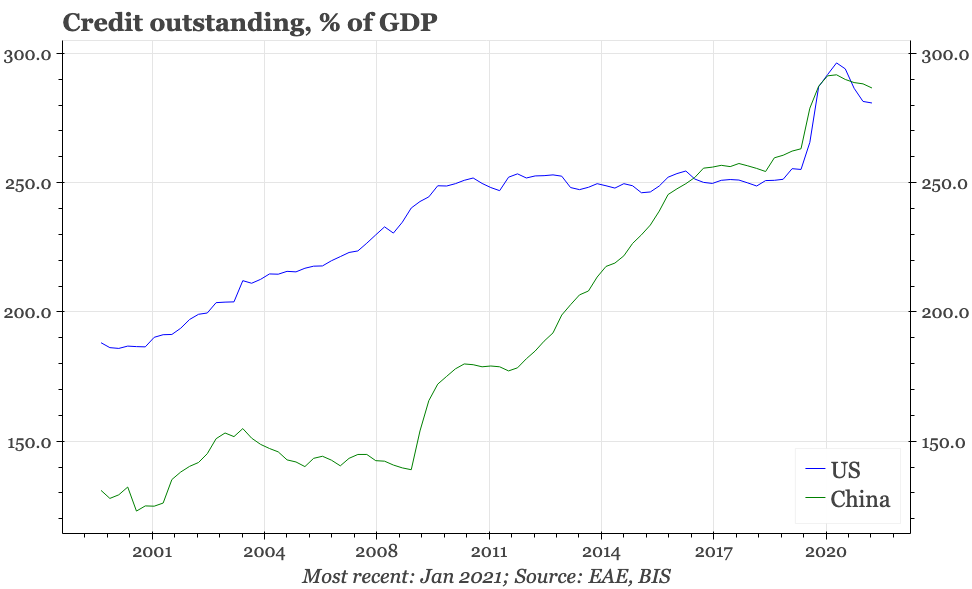

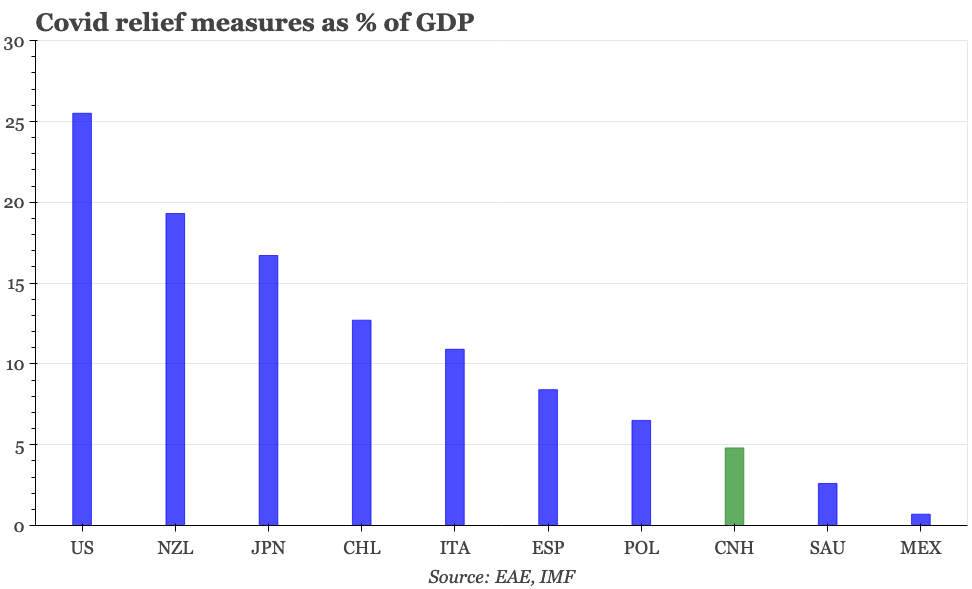

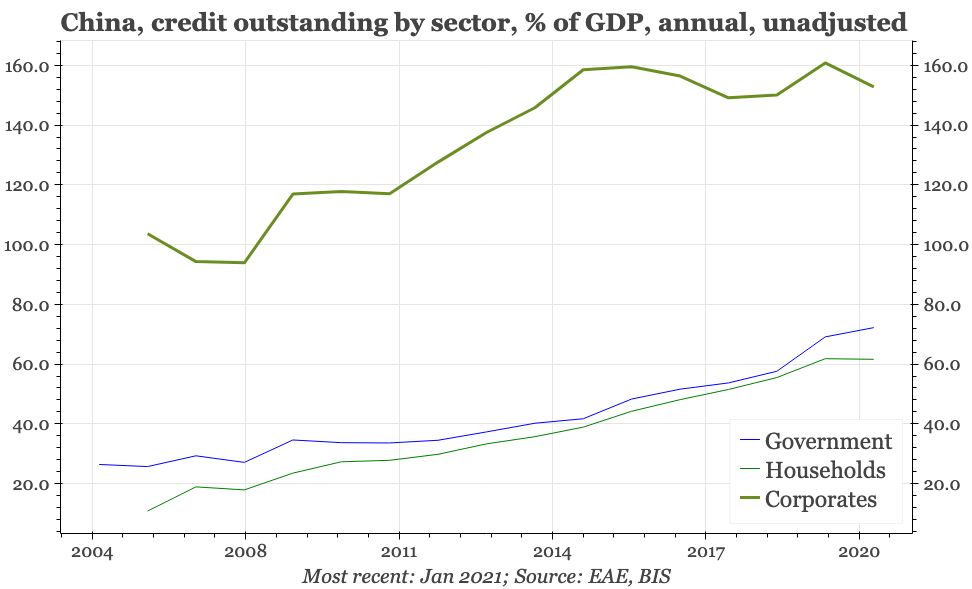

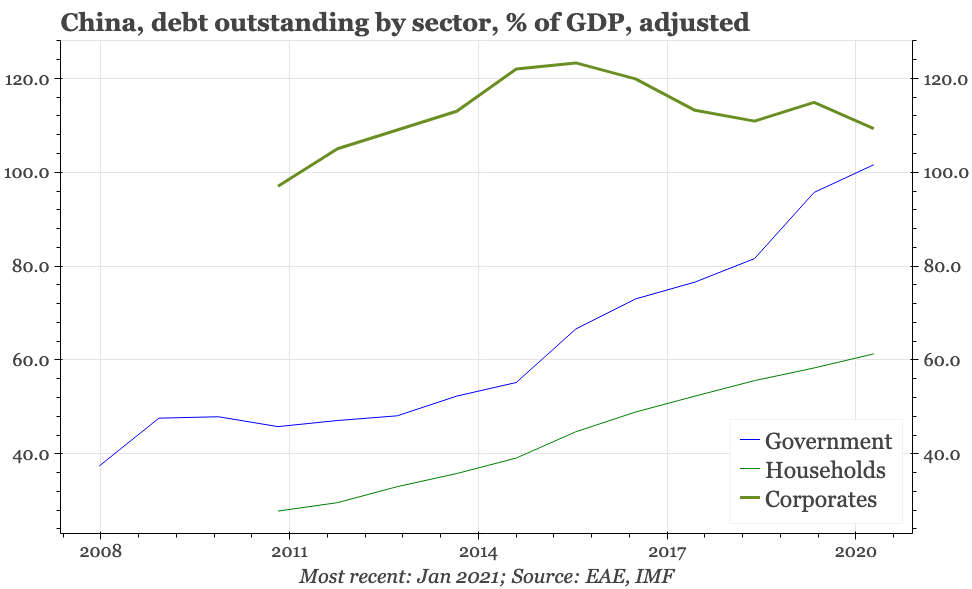

China, of course, did ease policy during 2020, but even then, it didn't look generous from a global perspective, and in 2021 Beijing's watchword for economic policy became deleveraging. And yet, according to the benchmark series from the Bank for International Settlements, if there was deleveraging in 2021, it was in the US, not China. The US's debt to GDP ratio fell more quickly than China's in 2021. Even before the new lockdown shock that was inflicted on the economy in 2022, leverage in China was once again higher than in the US.

Monetary tightness and NGDP

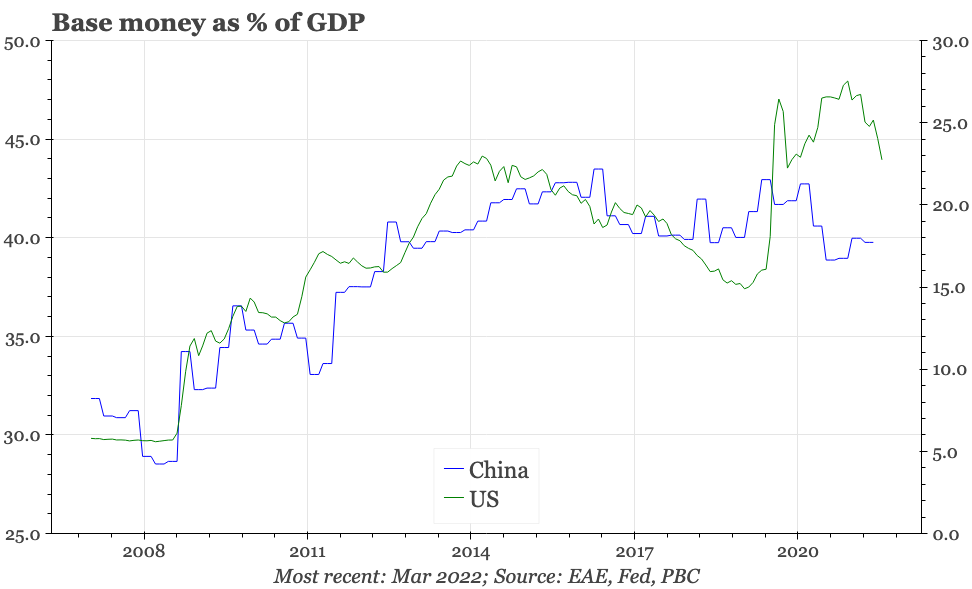

Of course, in monetary policy, China really didn't do any of the things that Guo Shuqing promised they wouldn't. It can be debated whether monetary policy overall was ever very tight – actual interest rates never rose in 2021, and are now 100bp lower than they were at the peak in 2018 – but China clearly didn't engage in the central bank balance sheet expansion that was seen in the advanced economies.

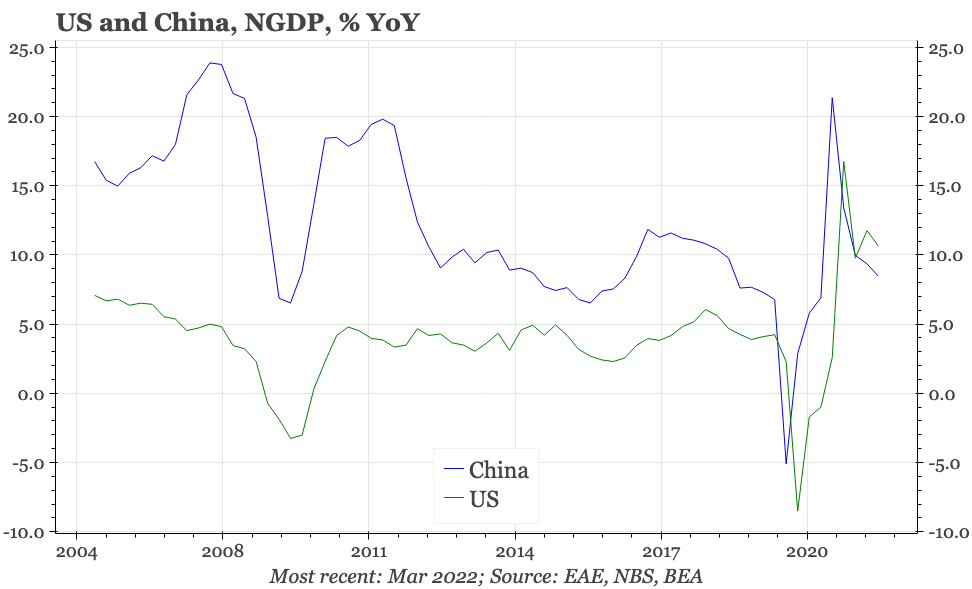

It shouldn't be a surprise that this is one of the explanations for China's difficulties in actually achieving deleveraging. There's certainly other drivers too, but the Fed's aggressive monetary expansion helped push up inflation in the US and so boost the nominal growth that is the denominator in debt to GDP calculation. US NGDP has been growing more quickly than China's for the last six months, the first time that has happened in many years.

It terms of the unfortunate trend of politicians in both China and the US to judge relative success as being in part the ability to outgrow the other, it would be easy to think this would be a pyrrhic victory. No doubt, Guo Shuqing and others would be arguing that high inflation isn't desirable because it will trigger a monetary policy tightening that will ultimately depress nominal growth. On the US side, that does seem likely – but after this year's unilateral lockdowns, NGDP growth in China is hardly going to be stellar either.

Lower taxes, not more spending

Anyway, while China might well think 10% inflation isn't a great solution for leverage, the experience of the last year or so should be a reminder that deleveraging campaigns that trigger low nominal growth aren't a foolproof answer either. The focus of “tightening” in 2021 was the real estate industry, with a hard drawing of the so-called “three red lines” on leverage in the industry. That did result in a sharp drop in reported lending growth to real estate developers, from over 20% YoY in 2018 to zero by 2022. But that still left the outstanding stock of debt in the industry very high, which was made more difficult to repay by the 30% collapse in property sales that was the flip side of the deleveraging push.

In any case, in terms of deleveraging, the real estate industry was the exception last year. Total credit in CNY terms in China rose by a bit over 11% in 2021. That is slow relative to the record post-2008, but was actually faster than in both 2018 and 2019. Debt growth did rise by 13% in 2020, which was a bit faster than recent years, but actually below the average 15.7% in the 2010s. Looked at from this perspective, and while China's deleveraging of 2021 isn't particularly obvious, nor is the policy easing of 2020. In the US, meanwhile, credit rose 5% in 2022, which was about average compared with the 2010s, but much slower than the 13.5% increase in 2020.

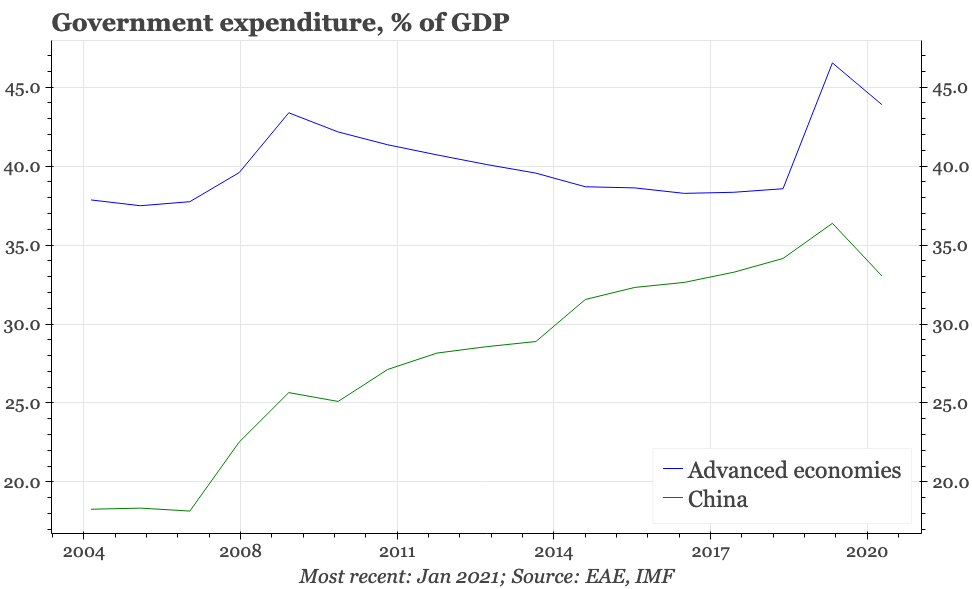

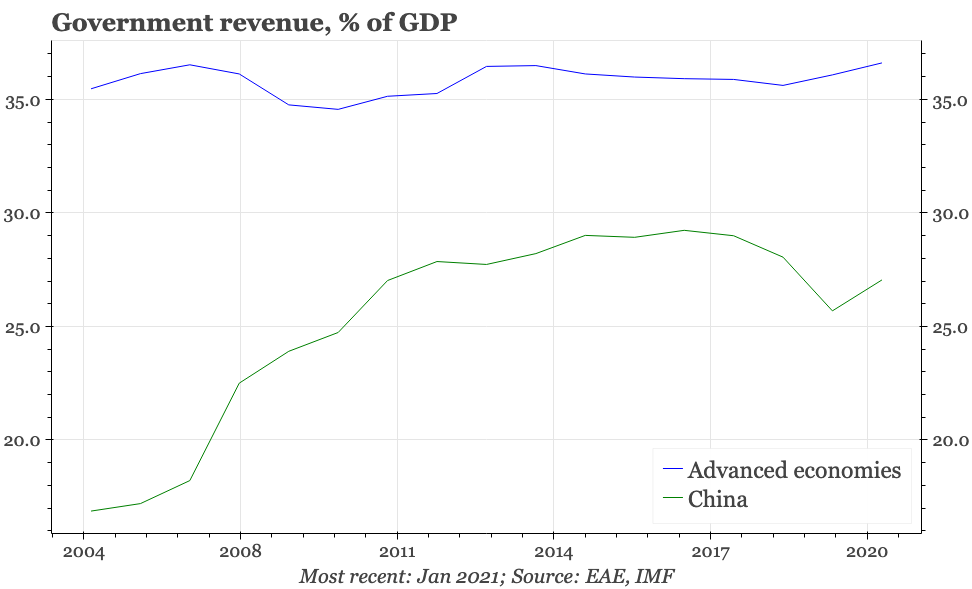

As in the US, most of the rise in debt in China in 2020 was due to borrowing by the government. But the policy direction financed by that official borrowing was quite different in China from the advanced economies. Elsewhere, the funds were used to finance spending: on average, government spending in richer countries surged by almost 8ppts relative to GDP in 2020. China's government did increase spending too, but modestly, choosing instead to focus on tax cuts. Spending did increase a bit in 2020, but then fell back. But in the first year of the pandemic, government revenue fell 3.4% relative to GDP, and remained low in 2021.

Companies benefit from direct government support

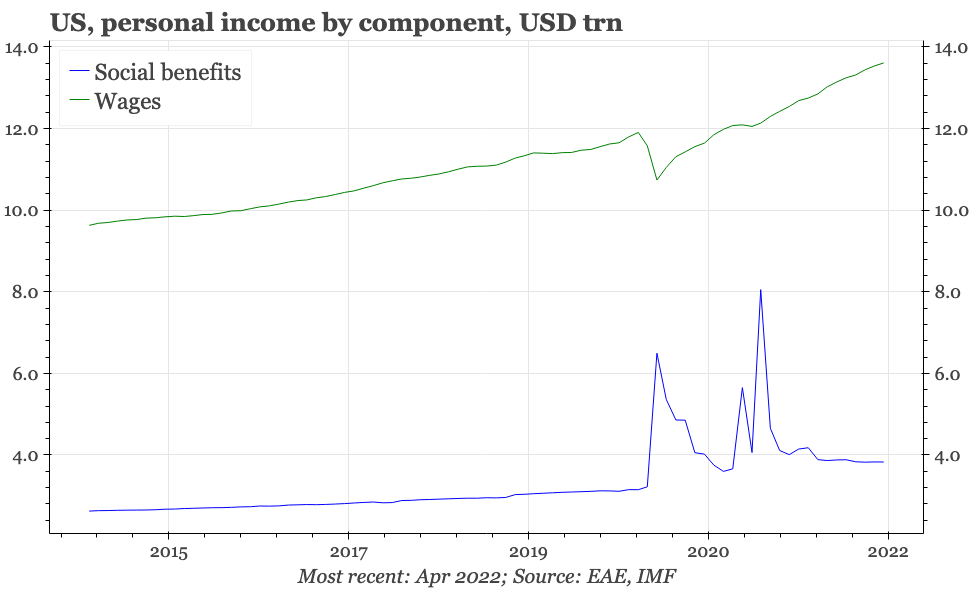

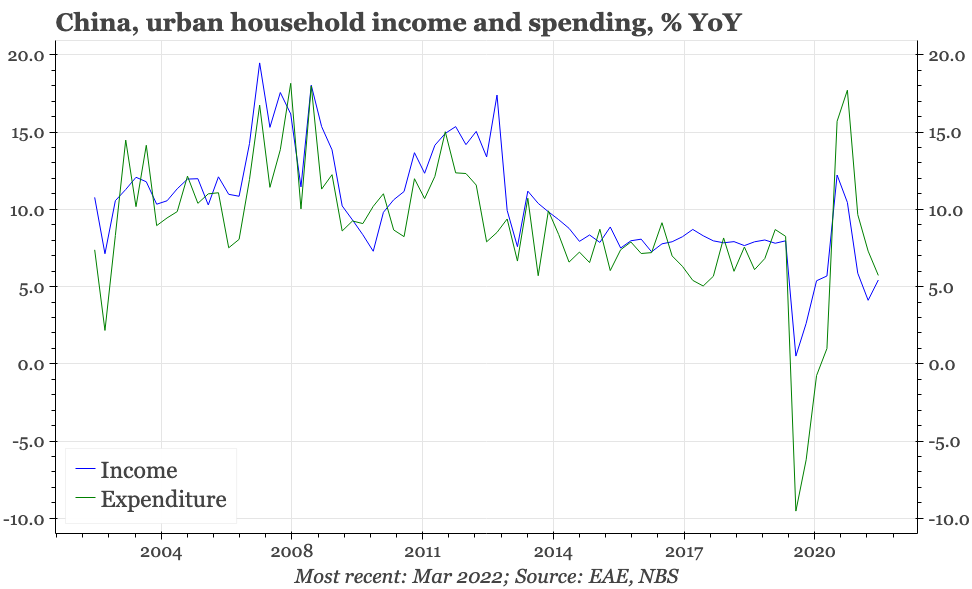

In the US the spending was used largely to finance income support for households, resulting in a surge in household incomes. In the first instance, that massively boosted the savings ratio, but has since fed into spending, boosting demand and so adding to the boost to nominal GDP provided by the monetary policy.

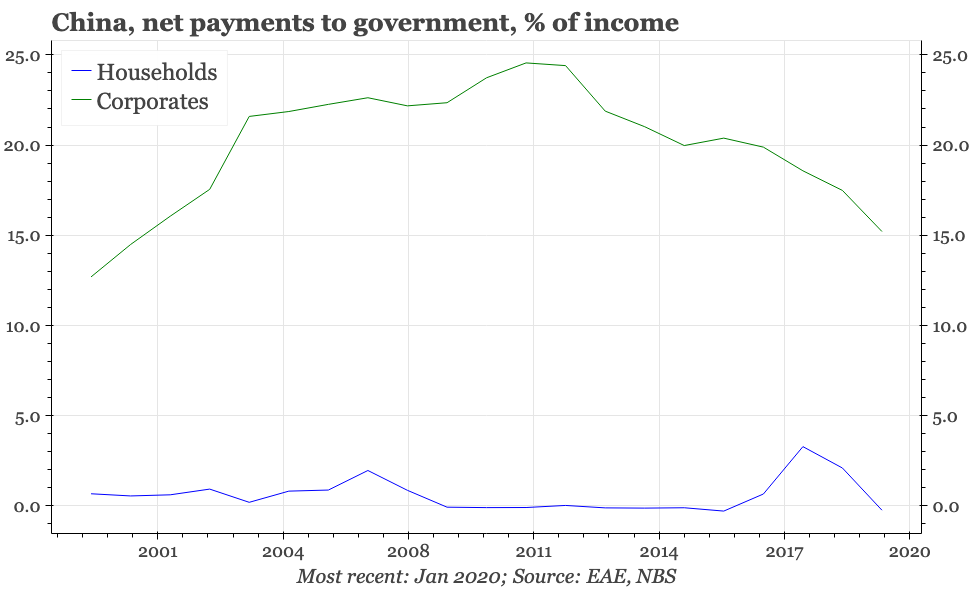

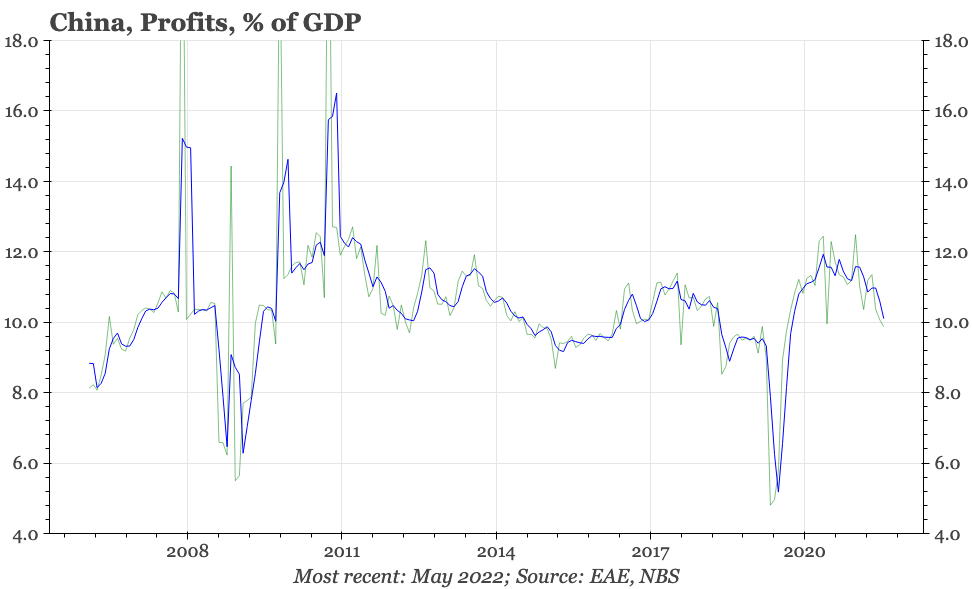

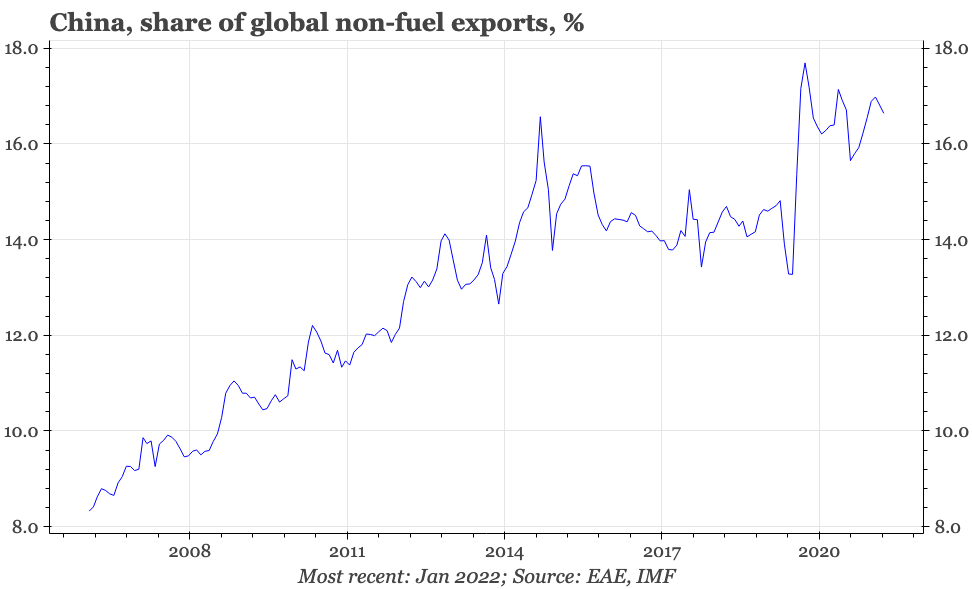

By contrast, in China, it was corporates were the targets of the government's 2020 largesse. Unlike household incomes, corporate profits rebounded very strongly after the Wuhan lockdown. To be clear, that wasn't only because of government tax policy: lower interest rates have helped, as did the sharp rise in commodity prices and exports as global demand recovered from the pandemic-induced recessions. But China's annual flow of funds accounts do also show a pronounced fall in the net payments the corporate sector is making to the government.

This same dataset makes clear that the easing of the tax burden on companies, like the seemingly secular fall in interest rates of recent years, is a policy that began well before covid first appeared. Given that the institutional bias of economic policymaking in Beijing to favour investment and companies over consumption and households has an even longer history, it is somewhat surprising that the corporate sector's burden has needed lessening at all. But that it has now been cut represents the immediate policy preferences of the premier, Li Keqiang. Even before covid he was pledging to:

avoid adopting strong stimulus policies, such as quantitative easing and excessive money supply. Instead, we will keep to the central task of supply-side structural reform and create conditions for steady economic performance by further advancing reform and introducing measures in accordance with market principles and the rule of law.

In that same speech, Li went on to say that within this over-arching policy programme, the first item was to “to energize market entities and improve the business environment”. A key element of that push has been to reduce taxes and fees for companies, as well as reforming the VAT system. That this was the direction of travel was clear before 2020, although the policy response to covid pushed the process much further along.

In and of themselves, these are welcome policies, and suggest strongly that it is misleading to generalise the government approach to the corporate sector from the tech crackdown of the last couple of years. It is reasonable to think that corporates which are less burdened by financial pressures and that are operating in a more conducive business environment will be able to perform more strongly.

To this point, as much as China's overall debt ratio has been rising in recent years, in the corporate sector it has stabilised. That's clear in the BIS data, but even more apparent in IMF estimates. The IMF estimates a much higher level of government borrowing than indicated by the BIS data, with the difference partly explained by a reclassification of borrowing by local government investment vehicles as sovereign rather than corporate. Using those, and China's corporate debt to GDP ratio now stands at around 110% of GDP, which is in line with Japan and Korea. With interest rates falling too, companies have benefited from lower tax payments, and moderating debt repayments too.

Households reliant on trickle down

However, a healthy corporate sector on its own is not sufficient to ensure a strong economy. The government knows that; or at least Li's remarks show that he sees boosting the corporate sector, at least in part, as a means to an end. The idea is that stronger corporates will in turn lift other sectors, by increasing investment, hiring more workers, and paying better wages, with the overall economy thus benefiting from higher productivity and stronger growth. As Li said just last week when visiting the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, to stabilise the labour market, the role of “market entities” – in other words businesses – is critical.

Unfortunately, there aren't strong signs that this is working, in data for either companies or households. Certainly, there are some signs of dynamism in the corporate sector, with the number of business registrations steadily rising. Some government data also suggest that corporate manufacturing capex spending has been increasing more quickly. However, even if that is true, it isn't the whole story. Flow of funds data show that for the corporate sector overall, income has been on the up, but capex has been flat-lining. The discrepancy, obviously, shows that companies overall have been paying back debt, which in turn helps explain the fall in the debt-to-GDP ratio. But it has also prompted some worries that instead of getting an economic boost from supply side reform, China is instead on the verge of a balance sheet recession.

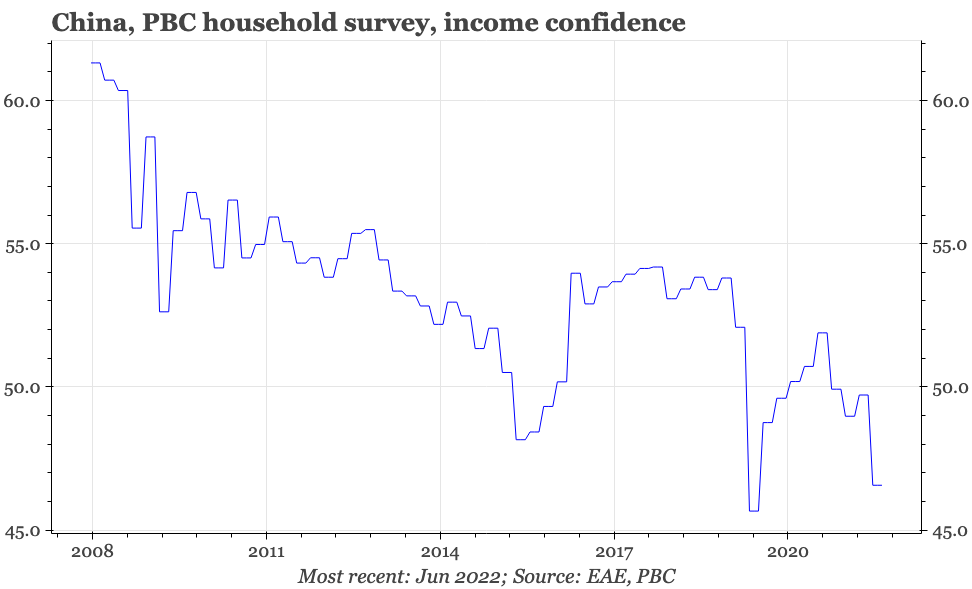

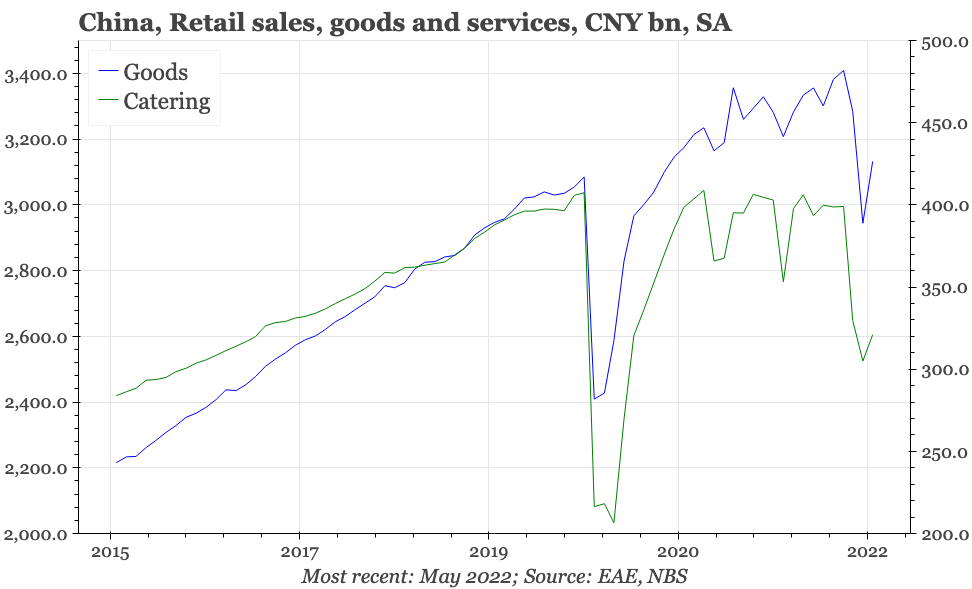

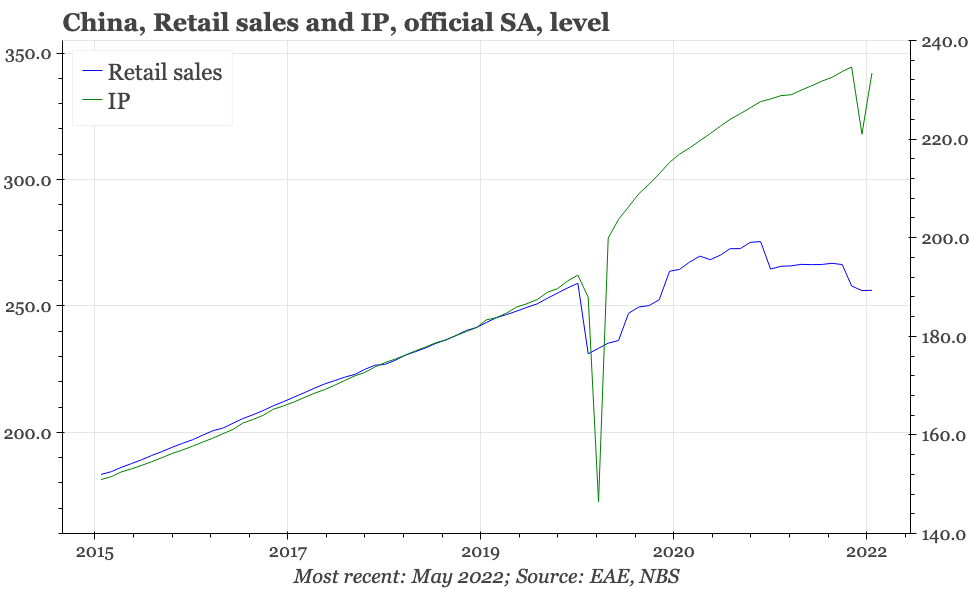

The picture is even bleaker in the household sector. While industrial production, corporate profits and company sentiment all improved rapidly after covid first appeared in 2020, household confidence, as well as growth in incomes and spending, all continued to look weak. Given that history, and the fact there's been no change in the policy response, it seems likely that the latest covid lockdowns would have contributed to a new step-down in economic indicators for the household sector. At the same time, and unlike the corporate sector, household debt growth for most of the last few years has continued to rise, and while interest rates on business loans have been cut, mortgage rates have remained stable. As a result, the interest burden on households has been rising.

Again, while his methods might be a bit different, in favouring the corporate sector, Li Keqiang has been very much going with the grain of usual policymaking in China. The flip side to that is a bias against providing direct policy support to households. That this preference exists has ironically become even clearer with the debate about common prosperity over the last few months. While there's been few specifics about exactly what methods will be used to achieve the broad aim, officials and government economists have made it is clear that households shouldn't be getting excited about big government handouts. Indeed, the article from Xi Jinping himself introducing common prosperity reads:

Even in the future when we have reached a higher level of development and are equipped with more substantial financial resources, we still must not aim too high or go overboard with social security, and stear clear of the idleness-breeding trap of welfarism

Outlook and implications

So, the government is making a big bet on the corporate sector. Perhaps, given enough time, this will work out, bearing fruit for the whole economy. After all, it isn't like the misbalanced nature of China's economy is a new phenomenon. The need for stronger household income growth has been discussed and debated for years, and yet GDP has continued to grow. If the doubling down on corporate support does work out, then it would likely mean an improvement in productivity, and be reflected in a rise in real interest rates.

Still, as much as going overboard on social security probably isn't the best answer to the weakness of confidence in the household sector, the for the whole economy going overboard with corporate help doesn't feel like an ideal way foward either. That will probably become more obvious in the next few months, because unlike in 2020, the corporate sector this time around won't be pulled out of China's lockdown-induced slowdowns by a big rise in external demand. With nominal growth likely to be low again this year, and the government having once again to loosen fiscal policy, the leverage ratio will rise again.

Given this, it would seem sensible to be doing something actively to lift the gloom that is currently prevailing in the household sector, and provide the economy with an alternative source of demand to investment and exports. But for the moment, this doesn't seem likely. Talk about a balance sheet recession is premature, but without some help for the household sector, China does look like it will have some elements of Japan's economic decline after the 1990s, with low nominal growth and rising debt. That being the case, it seems likely that in the medium-term bonds remain attrative in China, and particularly if US interest rates continue to fall, the CNY will be structurally strong.