China – taking stock

China's cycle remains weak. Perhaps money data and excavator sales for July will reinforce the message of the construction PMI that stimulus is feeding through. Otherwise, the risk remains of a growth accident that, via a weaker CNY, gets transmitted to the rest of the world.

Last week, this newsletter discussed the rising possibility of a real growth accident in China during the next few months. A reader (thank you) asked for clarity on what that meant. The idea would be “something” that wakes the rest of the world up to the cyclical downturn in China. This seems like a relevant issue to highlight, given the weakening of Chinese domestic demand is already significant, and yet financial markets elsewhere haven't seem so fussed.

There has, of course, been a lot of going in advanced economy markets, but still, a big slowdown in the world's second-largest economy should have implications beyond China's own borders. Assuming that is true, then it raises a second question: what the “something” might be.

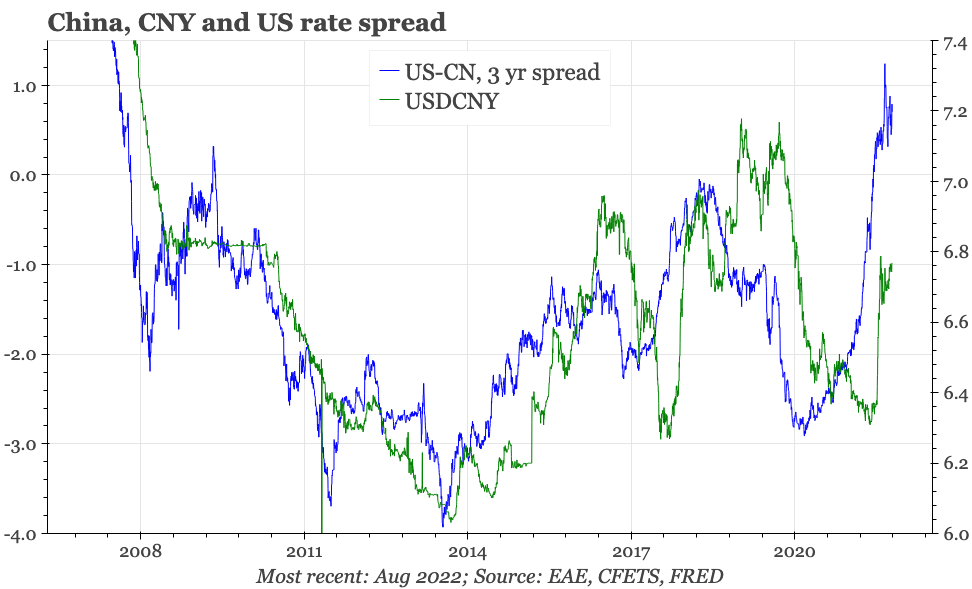

Given there's already been a significant sell-off in equities, Chinese stocks don't seem likely to be the source of a shock for the rest of the world. The same can't be said about the CNY, which remains near all-time highs on a basket basis, and against the USD has continued to lag the move in global rates.

It is often assumed that policymakers in Beijing have lots of tools to control the exchange rate. That isn't an unreasonable way of thinking, but then again, economic policymakers haven't been playing a particularly good hand over the last few months. If the cycle does continue to weaken, the CNY seems vulnerable.

Covid-19 is undoubtedly contributing to China's cyclical problems. That's not just via the lockdowns of 2022. Consumption has been weak ever since the virus first appeared, even though in the last couple of years China has achieved periods of zero covid. The disease, and the government's approach to managing it, appear to be contributing to a structural slowdown of consumption.

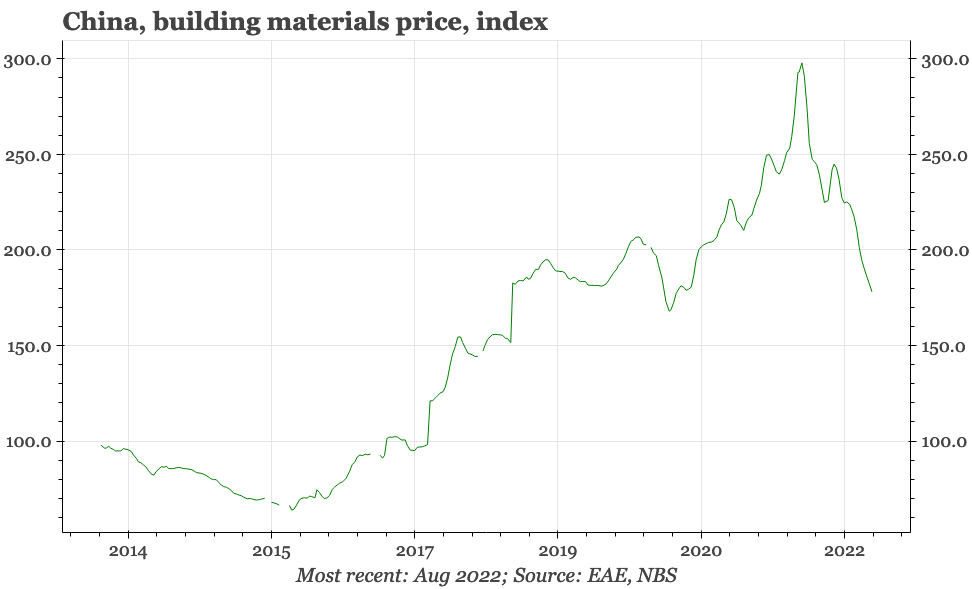

The bigger cause of the cyclical weakness though is that one of biggest and most inflated sectors in the economy, real estate, has been pushed into recession by the “three red lines” policy. The government, having previously struggled for so long to rein in the homebuilders, is now reluctant to throw them a lifeline. Policymakers do seem somewhat concerned, with calls over the last few months for “stability” in property, and continued incremental easing. But this cautious shift hasn't yet been effective at ending the sell-off in debt and equities of the listed homebuilders. As time goes on, there are signs of contagion, with the pain in the property sector starting to be felt by the upstream and downstream, banks, and by local governments.

The pain is likely to worsen further. Input prices in the July PMI fell. The trice-monthly industrial price data from the government show that prices were still falling through the end of the month, getting August off to a weak start. This trend points to PPI inflation returning to zero in the next few months; the decline in construction activity warns that the downside for producer prices is even bigger. Weaker producer prices will dampen corporate profitability, and via slower nominal GDP growth, push up the macro leverage ratio that has become a critical indicator for policymakers.

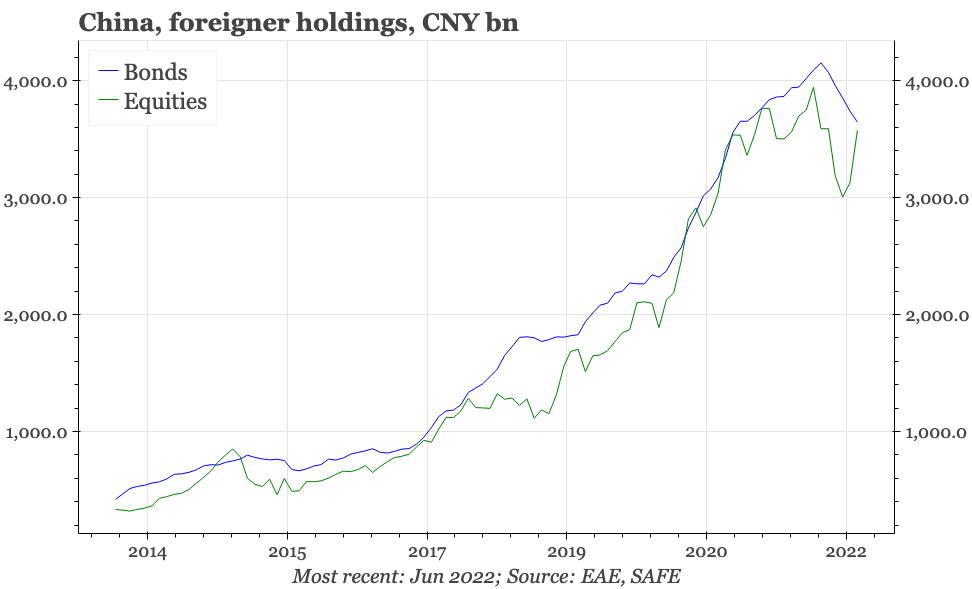

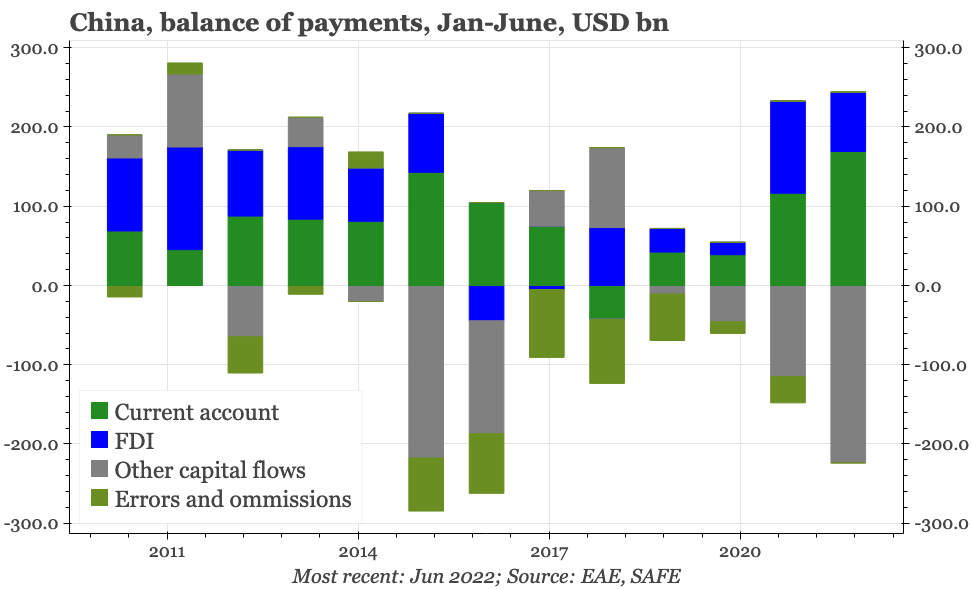

At the same time, external dynamics are turning against China. Leading indicators for the regional export cycle continue to deteriorate, with the ISM and IFO both down in July. Foreigner holdings of domestic bonds have fallen, and more broadly, last week's provisional Q2 Balance of Payments data point to an acceleration of net capital outflows.

These are all important developments, and increase the risk around China. That said, there are three factors that for the moment stand between all this negativity developing into a broader crisis.

First, the turn in external demand conditions is gradual, not sharp, with last week's export data surprising again to the upside. Exports most likely aren't as important to the domestic economy as real estate, but they still do matter, and the fact that they are for now still growing at least prevents the economy facing a double whammy of shrinking domestic and external demand. In addition, the strength of goods exports (and moderation in imports induced by the slowing of domestic demand) is supporting the current account surplus, providing a cushion against the capital outflows.

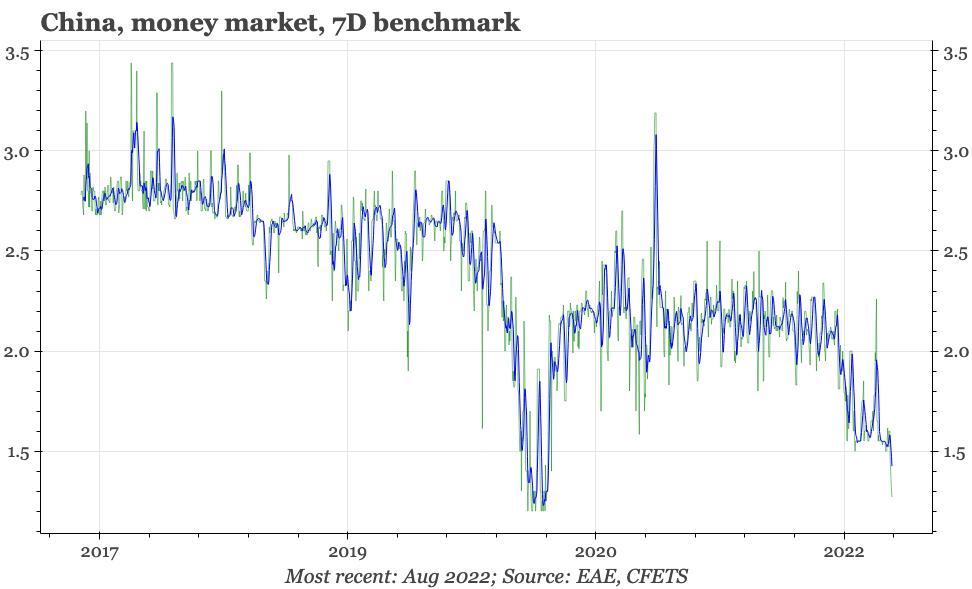

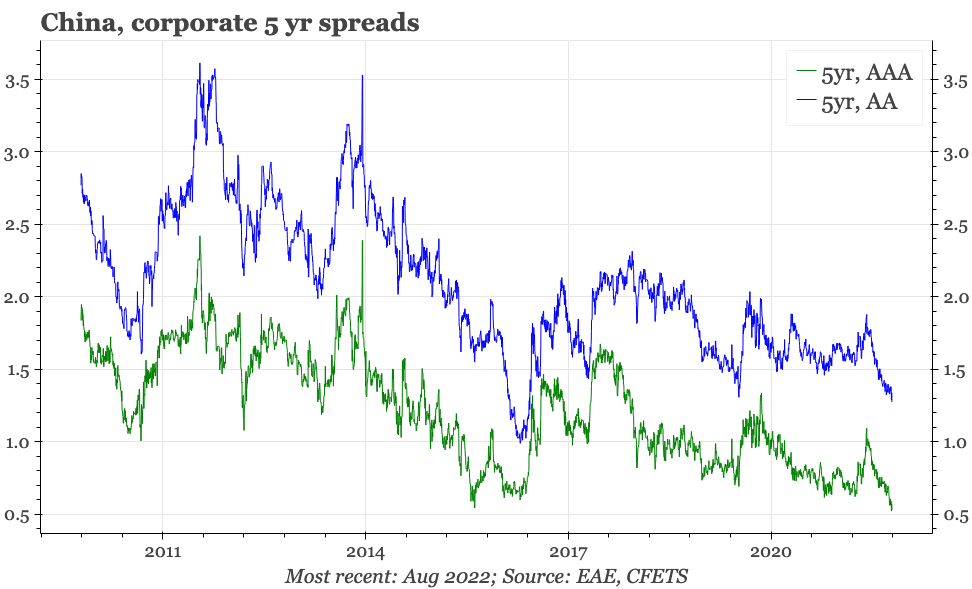

Second, while offshore listed real estate assets point to financial crisis, overall onshore financial conditions look relatively calm. To be clear, a financial conditions index has tightened somewhat in recent weeks, and that isn't helpful for the growth outlook. But short-end rates have taken a new step down, and credit spreads continue to tighten.

Third, though this is as yet more speculative, the government is supposed to be stepping up infrastructure spending. If that materialises, it can offset some of the pain for construction stemming from the contraction in property. This is worth highlighting because of the bounce in the July construction sector PMI. As just one indicator, that it itself if not enough to think that government infrastructure talk is transitioning into effective stimulus spending. But it does at least keep the subject on the table, and would look more significant if there is strength in this week's data for excavator sales and credit growth in July.

That said, with real estate and consumption already weak, and exports likely past the best, it would have to be a big rise in infrastructure spending indeed to single-handedly raise the economy. Perhaps that isn't entirely implausible, given the government's broadening of the concept of infrastructure to include all manner of tech-related projects. But it still seems highly unlikely that the overall economy can look stable when property is contracting, consumption weak, and exports slowing.

Some onshore economists have started to criticise the three red lines as a policy mistake. There also continue to be informed voices calling for direct help for consumers. So, there is a bit of room for optimism that the current policy trajectory will shift, and with it, the short-term prospects for the economy. Signs of a floor appearing under the property sector would in particular be an important step in starting to feel more constructive about the outlook.

Otherwise, though, China's economy will likely remain in cyclical trouble, with the downside risks growing given the likely slowdown in exports. Perhaps the weakening of global commodity prices in itself is showing that the world is starting to wake up to the economic weakness in China. The other asset price which has yet to move much is the CNY, and the currency therefore seems a likely candidate to reflect a growth shock in China in a way that affects the rest of the world.