China – taking stock

The cycle is weak, and yet the market was surprised the PBC cut rates yesterday. Central bank rhetoric had been suggesting rates had bottomed. But low inflation and signs of rising real rates make it more likely that rates fall rather than rise.

Searching for yesterday's data releases sent me into a mild panic. Not because of the data themselves – though they were bad – but instead because the structure of the National Bureau of Statistics homepage had changed. My first fear was this would necessitate a rebuilding of my data-collection infrastructure. Fortunately, that wasn't the case. The change was to put a section of “Political news” at the top of the page, with the titles of its four lead stories today leading with “Xi Jinping...”. This probably shouldn't be described as a cosmetic change, and it is certainly a sign of the times.

The first sentence in the NBS's statement summarising the economy also featured Xi, saying that under the leadership of him and the central authorities "supply had continued to recover, unemployment and prices are stable, there's been good growth momentum in external trade, people's social protection has been strong and forceful, and that the economy has continued its recovery trend". The comments on prices and exports seem reasonable. The others offer quite the optimistic interpretation, though the NBS in other remarks did highlight disruptions caused by Covid-19 issues and hot weather.

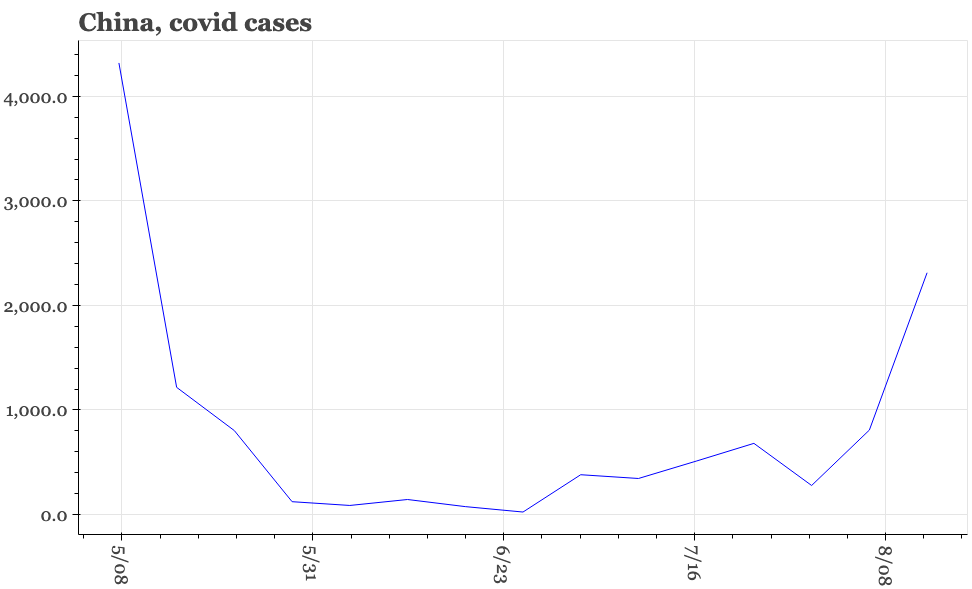

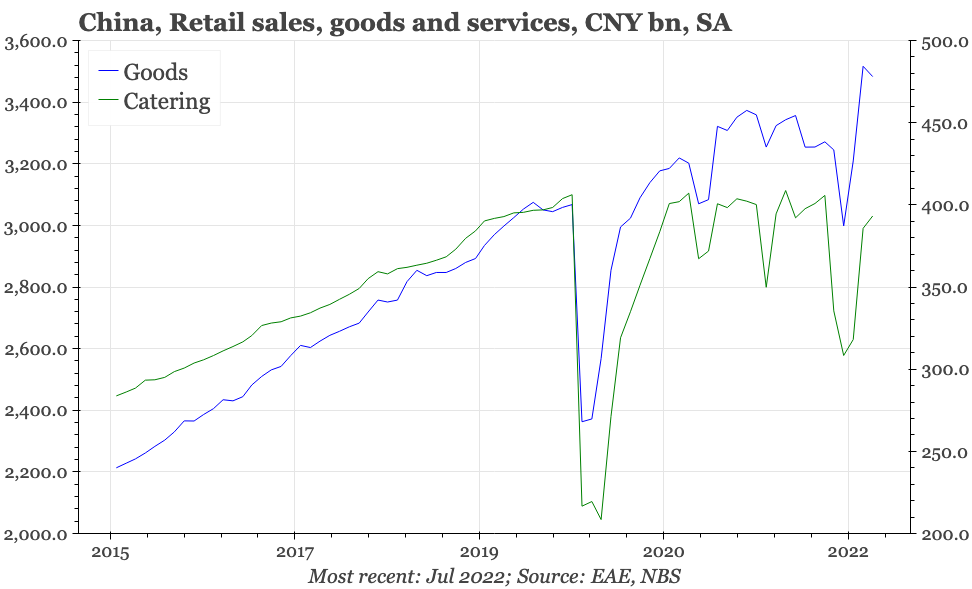

The weather has been particularly hot in different parts of the country. As for covid, that undoubtedly caused some pain in July, but yesterday's data showed consumption in general, and spending in restaurants in particular, rising from June. In this respect, the economic damage from covid is looking likely to be bigger in August. Yesterday's case count of more than 2,500 is higher than at any time since early May. One of the outbreaks is in the tourist hotspot of Hainan. The resultant lockdown and reports of tourists being unable to leave is unlikely to boost domestic travel in the coming months.

In addition to covid and climate, the other challenge for the economy is construction. The NBS spokesman expressed hope that local level loosening was lessening the downturn in property, and that this would continue in the next few months. The YoY change in sales has improved a bit. But in absolute terms, property transactions in July were lower than any time since 2015. That doesn't offer any springboard for a recovery in construction.

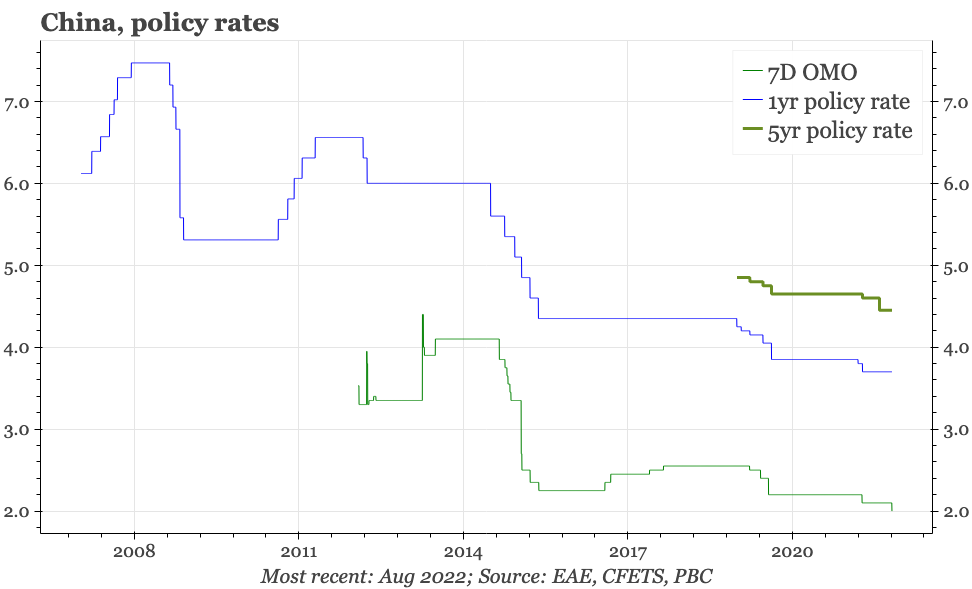

If not relative to the thinking of the NBS, then at least when set again the consensus of the market, the data released yesterday were poor. Indeed, all the major headlines came in below the average of economist estimates. Given this weakness, it would be usual to think economists would be expecting more policy loosening. But the market was surprised when the PBC yesterday announced 10bp cuts in both the one-year MLF and seven-day reverse repo rates.

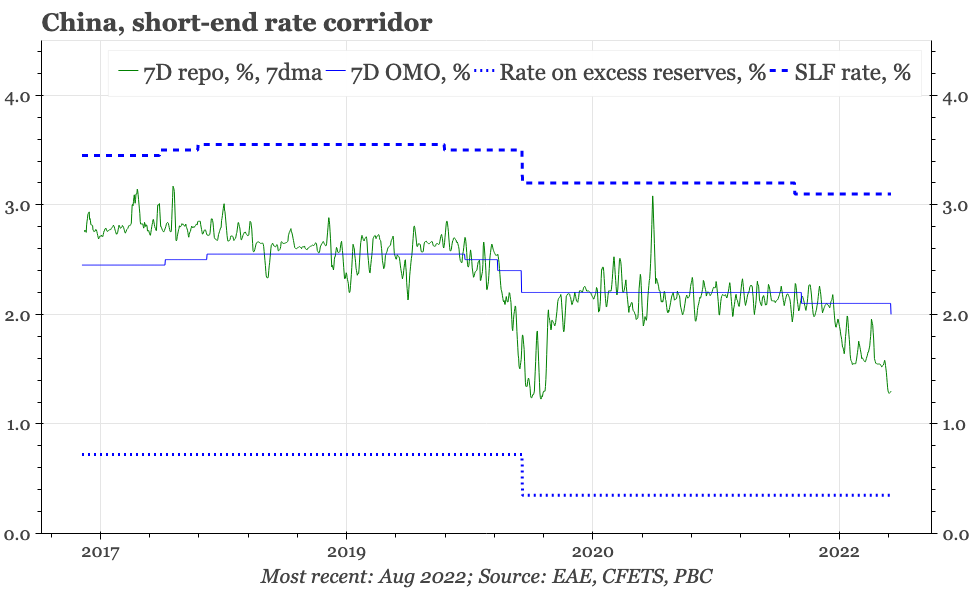

To be fair, the PBC hadn't set up the market to expect these changes. In the summary of last week's Q2 monetary policy report, the central bank added a sentence on the need to "closely monitor the changes in the inflation situation at home and overseas", and also included a box highlighting “the need to guard against structural inflationary pressure”, forecasting that in the rest of the year CPI inflation might temporarily exceed 3%. The central bank's report also stated that the stability since Q2 (until yesterday) of policy rates was helpful for balancing domestic and external sectors when the rest of the world is tightening. In addition, the PBC has also been saying liquidity is already ample, and seems to be getting concerned that the very low level of market rates has been resulting in a resurgence of leverage within the financial sector.

It doesn't feel like this is the first time in the last couple of years that the market has been surprised in this way. Indeed, while I haven't dug out the data yet to look at this in detail, it does seem the PBC has developed a knack at changing rates just when the market least expects a shift. That's quite the contrast with the way central banks in the developed world go about policy, with great efforts being made to push the markets in the direction the Fed and others want to go.

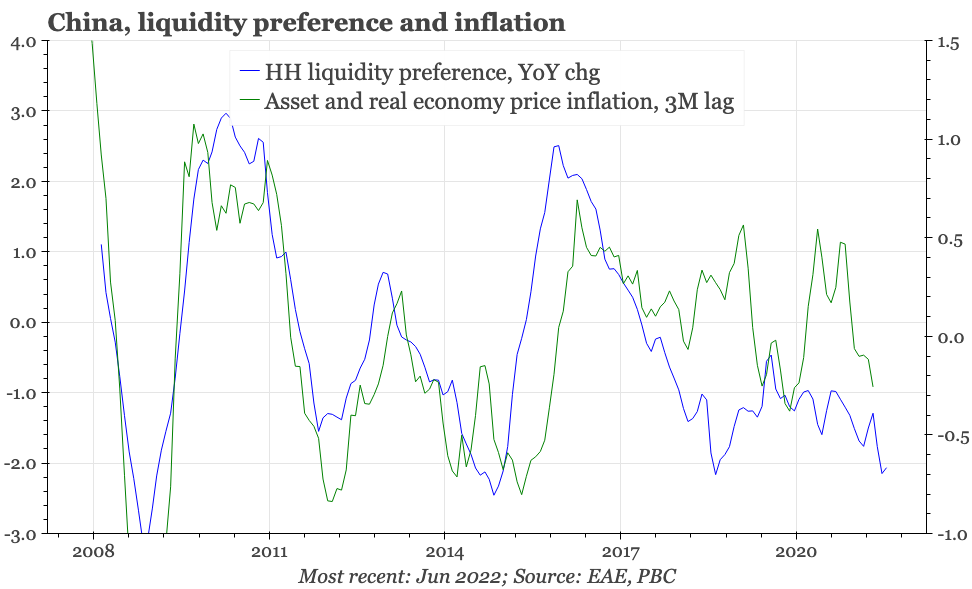

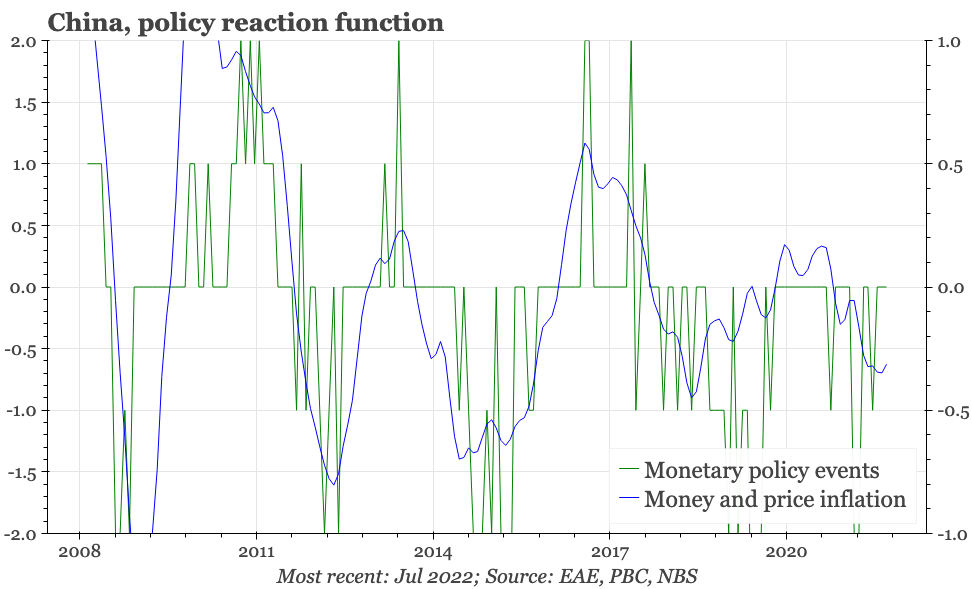

Ignoring PBC rhetoric and focusing just on economic reality, then yesterday's interest rate cuts weren't surprising, and further reductions look likely. That is the conclusion of a simple reaction function model for the central bank, which includes real economy and asset prices, and credit growth. Just focusing on PPI and CPI isn't enough, given ample evidence the authorities also care about asset price inflation, in property in particular. Changes in monetary growth also tend to drive policy changes from the PBC because they give the central bank - which needless to say isn't independent - the justification for arguing with the rest of the bureaucracy that policy change is necessary.

Using this framework, then to think that rate cuts aren't likely is to argue either that generalised inflation is indeed about to rebound strongly, or that the reaction function has changed. Personally, I think deflation is more likely than inflation. The grounds for arguing that there's been a change in reaction function seem stronger, though still not overwhelming.

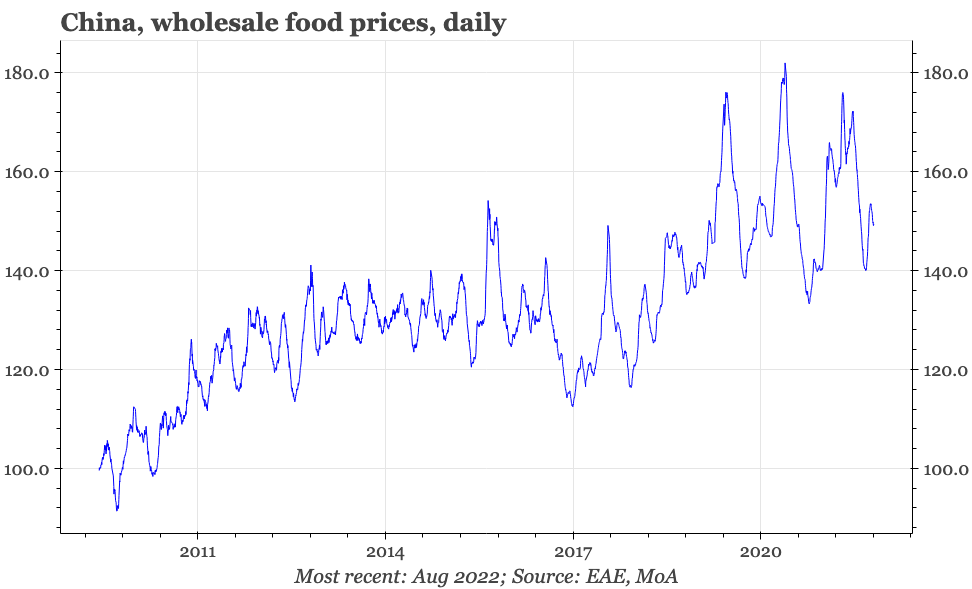

The PBC wouldn't be a central bank if it wasn't thinking about inflation, especially when growth of CPI in the rest of the world is currently so strong. The monetary policy report highlighted three specific factors that would push up what it termed "structural" inflation: consumption recovery post-covid; an expected rise in the price of food, especially the pork price cycle; and the increase in the global price of energy.

If there is a recovery after covid, then demand-driven inflation in the services sector will become a concern. More generally, if the overall economic cycle starts to gain upwards momentum, then inflation can be expected to rise. But right now, Covid-19 continues to slow consumption, and outside a crisis, overall economic activity in China feels like the weakest it has been since at least 2015. All the indicators for PPI inflation point to a continued slowdown, with likely YoY price declines by the end of the year. Core CPI also looks likely to remain contained at less than 1% YoY. Food price inflation might well continue to rebound, but the rise will have to be strong indeed to single-handedly create an inflation problem in China.

As for the authorities' reaction function, it does feel that macro policy in recent months has lacked the decisiveness that has been evident in economic downturns in the past. As argued here previously, one factor is likely the contradiction between the official desire to support investment rather than consumption, at the same time as wanting to avoid a further rise in the leverage that has been one of the consequences of this policy preference in the recent past.

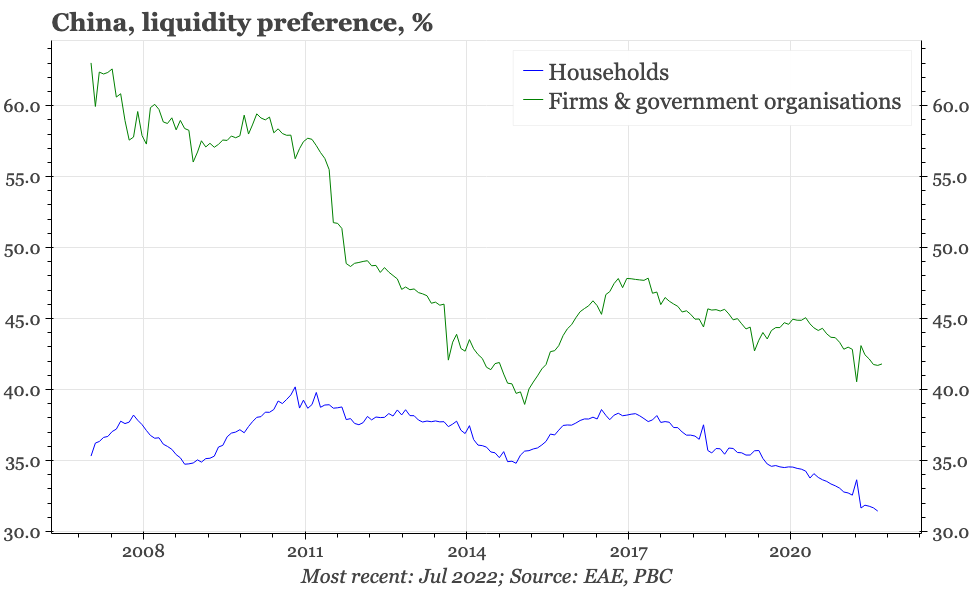

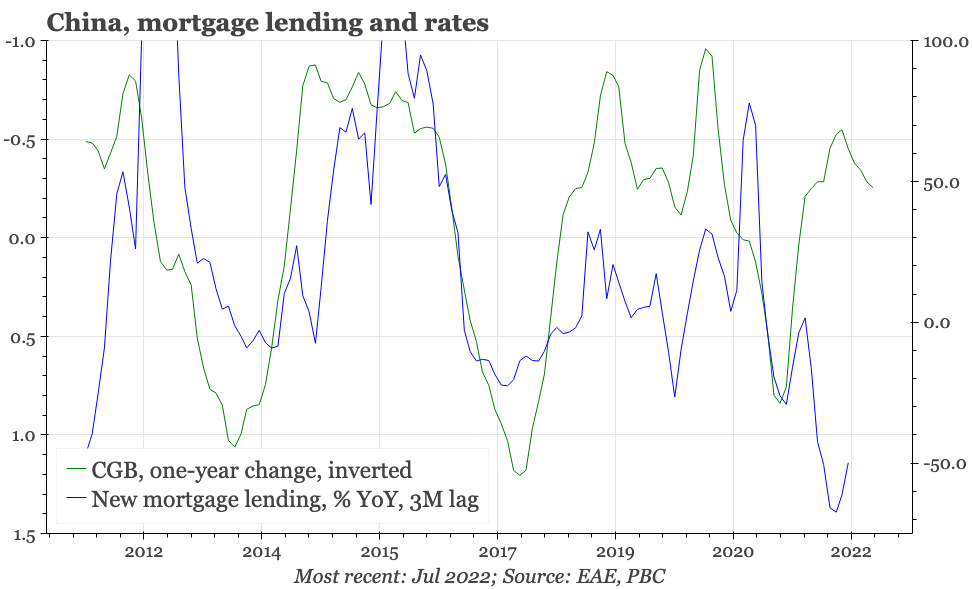

It is also becoming popular to argue that interest rate cuts won't be effective in resolving China's current economies woes. Again, that isn't completely without justification. Interest rates aren't boosting property market demand in the way they have previously. That said, savings behaviour does hint that perceptions of real rates in China are rising, with both households and corporates continuing to move money into time deposits. That isn't a helpful development for the current economic cycle. If inflation isn't going to rise, then it is probably useful to have lower nominal rates instead.