China – Beijing blinks

Policymakers have blinked, announcing a raft of measures to support property. On their own, these aren't sufficient to have conviction that the economy will turn. But with improvement in the construction PMI, they do suggest that for the first time in a while, not all the cyclical risks are down.

Taking stock

Property

The period before China's early October week-long holiday has almost felt like a return to the good old days: late Friday evening announcements of interest rate cuts, joint agency statements announcing easing measures, talk of banks being told to ratchet up lending before the end of the year. Moreover, all these measures have been aimed at the property market, which used to be the main beneficiary of government policy largesse, but in the last couple of years has been neglected, with an official line that it shouldn't be used as a tool for short-term economic management.

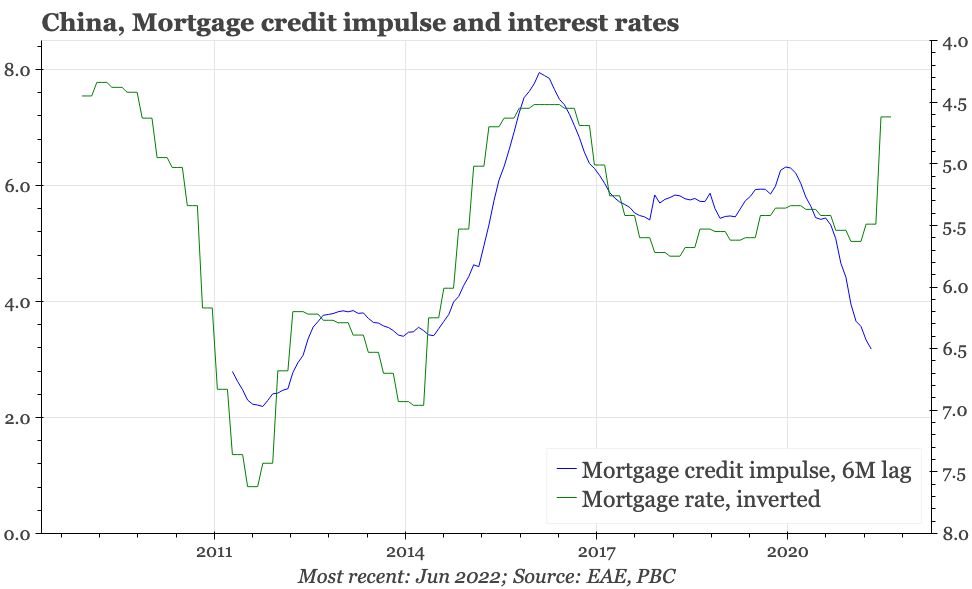

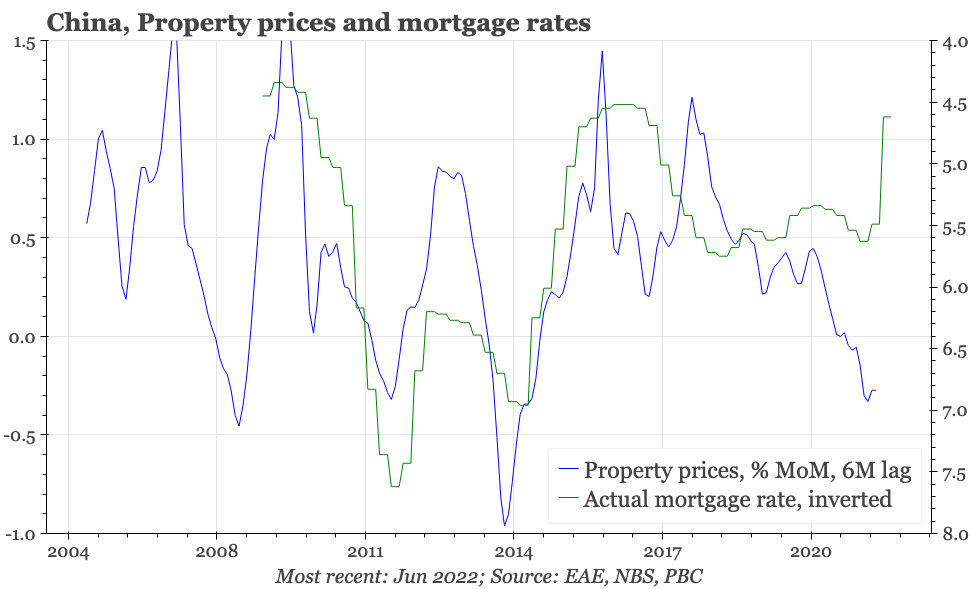

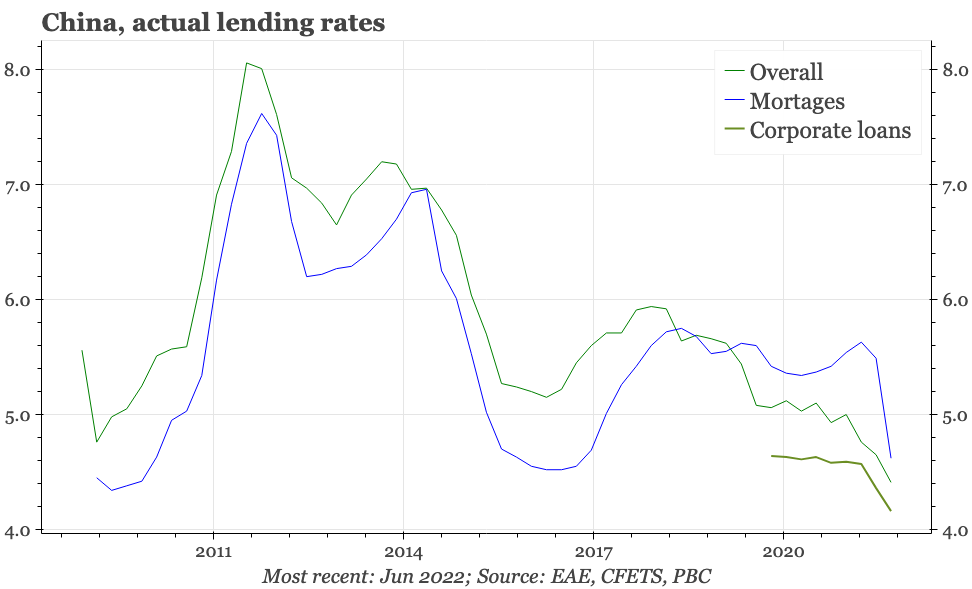

Significantly, that phrase hasn't been made an appearance in government statements in recent days (though policy is, apparently, sometimes still being made on the basis that “property is for living, not speculation”). And the policies announced in late September don't entirely break with what has been going on for most of 2022. Of the measures announced, two were aimed at reducing mortgage costs – cuts in rates charged by the Housing Provident Fund, and a temporary (and region-specific) removal of the floor on mortgage rates for first properties. But that comes after a period when mortgage rates had already fallen more quickly than at any time on record.

Still, the policy announcements of the last few days do stand out. With the latest cuts, the nominal cost of borrowing for a home will likely reach record lows. There appears to be a concerted attempt to get the property market going, with three official property policy announcements in just a couple of days (in addition to the rate cuts, the MOF announced tax rebates on property sales). The mortgage floor and the tax rebates will only apply until the end of the year, seemingly being structured that way to address the concern that the previous steady trickle of measures had intensified a wait-and-see attitude, encouraging potential buyers to hold on for yet better policies to emerge.

The extent of the overall shift can be sensed from the statement from the latest quarterly meeting of the PBC's monetary policy committee. These meetings aren't of nearly the same importance as MPC meetings elsewhere. In China, the MPC doesn't decide on policy, and there's not much effort to publicise its proceedings: the Q3 session was held on September 23rd, but the statement was only released on September 29th. However, that was when all the other real estate policies were being announced, and comparison with previous statements does provide some context on how far policy has moved.

So, in its statement back in June the MPC had just this to say on real estate:

The PBC will protect the legitimate rights and interests of housing consumers, better meet the reasonable demands of homebuyers, and foster a virtuous cycle of the real estate market for its sound development.

But this time around, the message is much more fulsome, with the PBC pledging to

adopt city-specific measures and use the policy toolkit fully and effectively to meet the rigid demand for housing and the needs to improve living conditions. The special lending facilitating real estate delivery will be put into use at a faster pace, even with appropriately higher intensity if needed. To protect the legitimate rights and interests of home buyers and boost the sound development of the real estate market, the PBC will guide commercial banks to provide supplementary financial support.

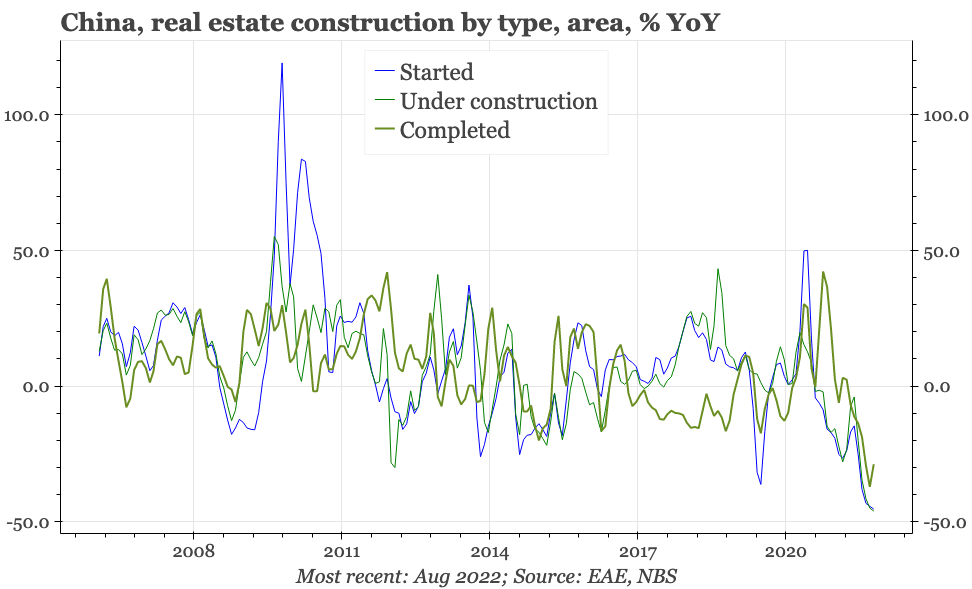

For the last few months, it has been property buyers that have been the main target of policy easing. While there haven't been specific announcements of supply-side help this time, this statement from the MPC does suggest that more help is being offered to developers, including a mechanism to ensure stalled developments are completed, and perhaps including additional loans to developers too. That mechanism to clear the backlog of unfinished projects has been poorly disclosed, but much-discussed, and a bump in completions was the one bright spot in construction data for August. As for increased lending, media have reported that banks have been urged to increase real estate loans by CNY600bn before the end of the year.

That said, at least by close of business on Friday, all this policy activism had yet to have a discernible impact on developers, with listed debt actually closing lower than it had seven days earlier. That weakness is the very reason so much policy has been announced. As long as developers remain in so much trouble, it is difficult to imagine stabilisation in the economy, let alone any upturn. Indeed, there remains an appreciable risk of some kind of financial accident that drags the economy down further.

Currency

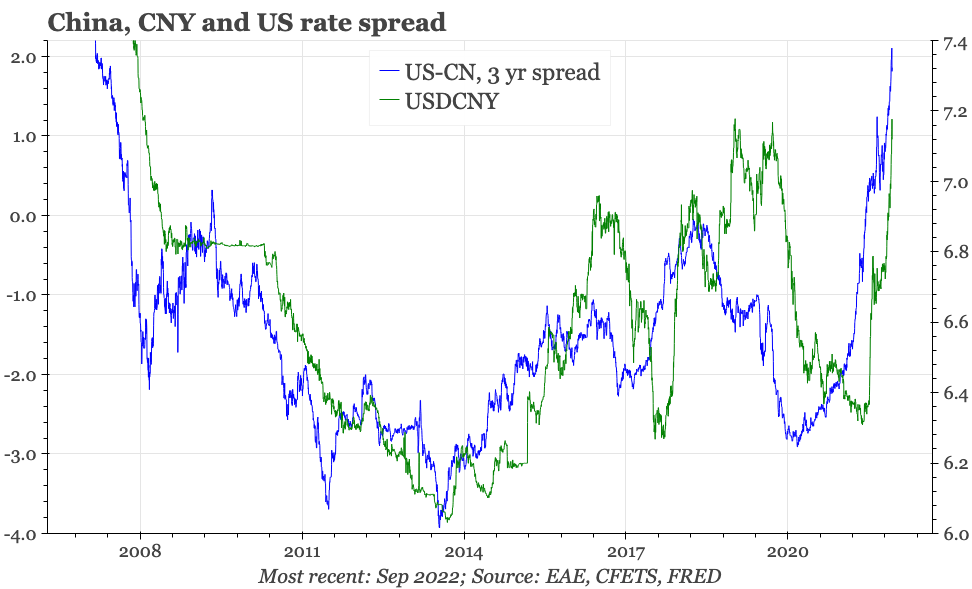

As a reminder of those financial risks, last week was also a particularly lively one for the currency. $CNH spiked up to above 7.25 on Wednesday, the weakest since 2008. Before then, the PBC had already used its formal tools to try to slow down the depreciation, raising the reserve requirement for forwards to 20% at the beginning of the week. On Tuesday, it resorted to window guidance. In the evening, the PBC issued a statement saying that the previous day there had been a virtual meeting of the “Foreign Exchange Market Self-Regulatory Framework”. By Thursday, the $CNH was back to 7.14.

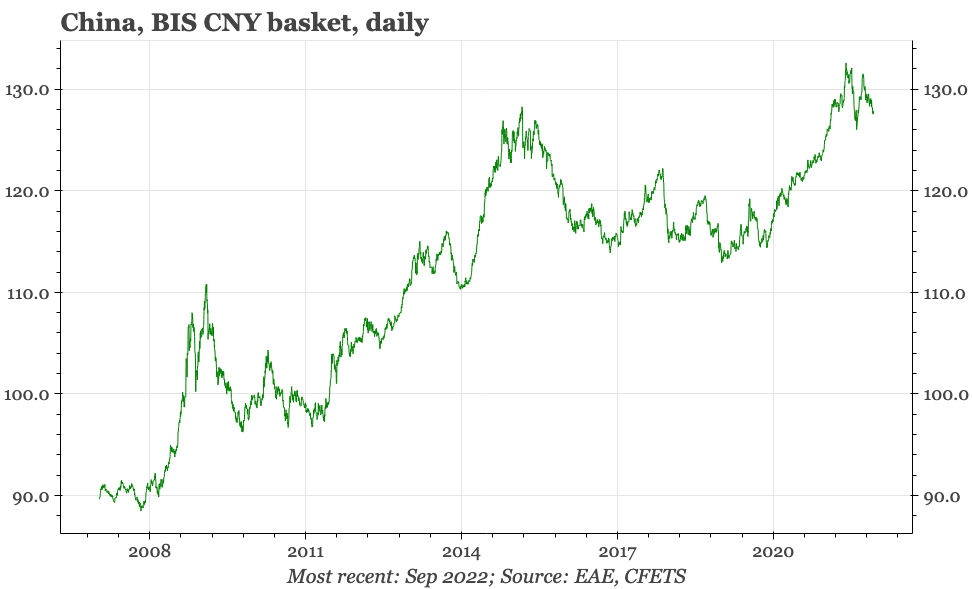

Clearly, the pressure on the exchange rate is far from being all about China. And the moves in the CNY to date have been pedestrian compared with those in many other currencies. Even now, the CNY on a basket basis is close to record highs, and that strength is consistent with China's structural external surplus. Still, from a cyclical perspective, the currency still feels strong, with China being the only major economy that is cutting rates while the Fed tightens. The longer China's cycle remains weak, the longer rates will be depressed, and the more potential there is for a self-reinforcing cycle of currency weakness and capital outflows.

Outlook

Which brings us back to the property measures, and whether they will be successful in turning the cycle around. Overall, it remains reasonable to assume that they won't be. As the fall in mortgage rates shows, at least for buyers, property policy has been on a loosening trend for a while, and yet the real estate sector remains weak. There is some probability that policy is now too little too late; that the structural, multi-decade belief that property prices could only ever rise has been broken; and so the nominal rate cuts aren't having the same cyclical impact on property because falling price expectations mean real rates are actually rising.

I think though that events of the last few days have started to shift some of the risks around the economy. That's not just because of the property measures, but also because of the rise in the last couple of months in the official construction PMI, which suggests – perhaps – that the government's infrastructure push is starting to bear some fruit.

Neither development is convincing enough on its own to start believing in a turn. That's particularly when zero covid continues to weigh on the economy, and exports can no longer be relied on to produce growth. For any real turn, the government likely needs to provide more direct financial support to property developers, and income support for households. However, while for the last few months all the risks have seemed to be to the downside, the hints of a turn in construction, and new support for property development, are starting to even out the risks.