China – where we're at

The Covid-19 situation has improved, but not by enough to declare the all-clear. Policy has eased, but not by enough to ensure recovery when lockdowns do end. There's more debate about giving help to households, but further loosening still seems likely to focus on companies and investment.

In terms of economic re-opening, the good news is the case numbers outside of Beijing and Shanghai remain low – 141 as of yesterday – and falling. The bad news is that in two of the biggest, richest cities in China, the situation remains rather tense. In Shanghai, restrictions are being eased. But while overall case numbers in the city have fallen, and on most days there is zero transmission outside of people already in quarantine, that isn't yet true on all days. Meanwhile, Beijing recorded 83 new cases yesterday, which isn't a large number relative to outbreaks elsewhere, but is the highest ever recorded in the capital.

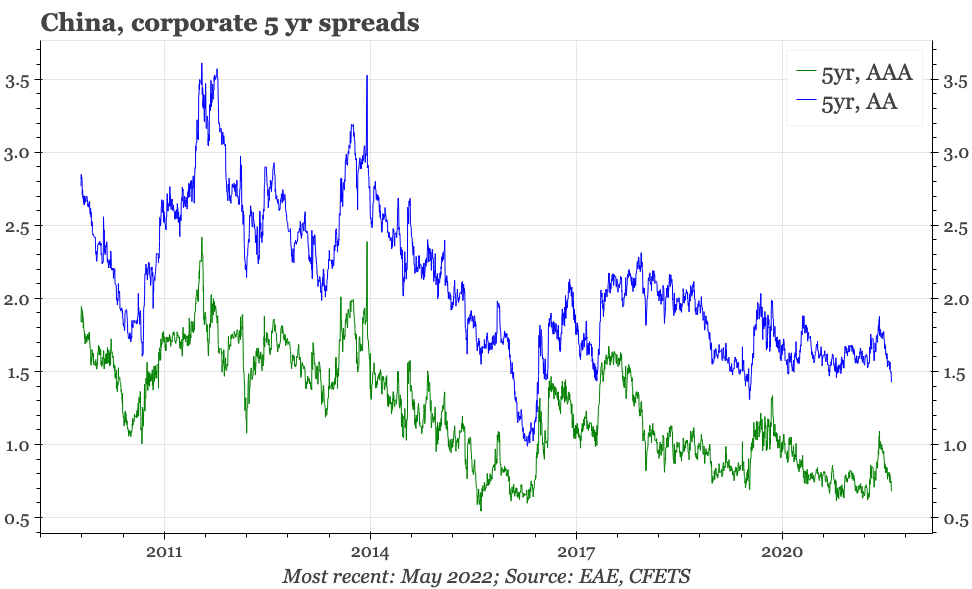

As long as Beijing – or any other significant economic region – is teetering on the edge of a lockdown, the message from any economic leading indicators is moot. But if the Covid-19 situation in Beijing controlled, then it will be somewhat helpful for activity that the fall in short-end rates is persisting, spreads have tightened once again, and after the recent depreciation, the CNY on a basket basis is a bit weaker.

Some of this is similar to the situation that existed around the end of Q120, when China started to exit the economic hole dug by the first Covid lockdown. Compared with two years ago there also continues to be similarity in the policy language once again circulating in Beijing, particularly the stress on “resumption of work and production”. Overall, the government's intention does seem to be to re-use the play book used to orchestrate recovery in 2020. That being the case, we can expect continued targetted monetary easing, greater government funding for and spending on infrastructure, and in the context of these supportive-but-not-loose macro conditions, the use of administrative measures to guide companies back to work.

This might be enough to once again normalise China's economy, but it feels like this time around, policy will need more oomph. Two years ago and exports were just about to take a big step-up, while this time there's growing evidence that external shipments are at least slowing, and perhaps sharply. Chinese exports might manage to outperform a slowdown in global trade if anything comes of the recent talk of reductions in the tariffs imposed on China by the Trump administration. But it is still uncertain that there will be a tariff reprieve, and in any case, if global demand is slowing, Chinese exports won't escape unscathed.

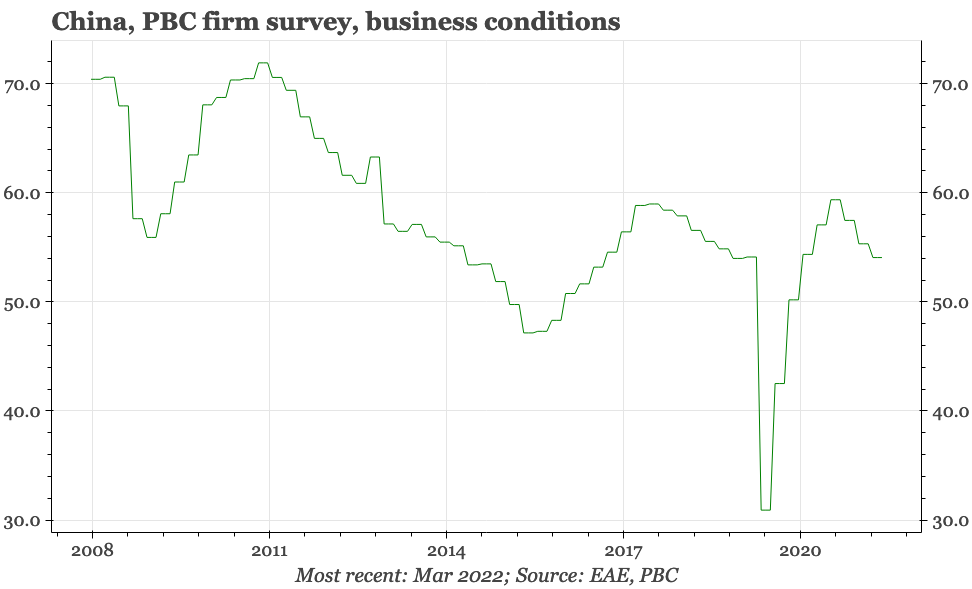

At the same time, the domestic economy is also much weaker. That's partly because of the problems in property, with the government for much of 2021 seemingly intent on engineering a structural downturn in real estate. By Q421 the government seemed to be regretting squeezing the sector quite so hard, and so started to engineer some relaxation. But the resultant rebound in real estate hadn't progressed very far before the latest Covid-19 outbreak triggered the closing down of one of China's most important commercial regions. At the end of 2019 national property sales were rising around +10% YoY; in March this year they were contracting more than -20% YoY.

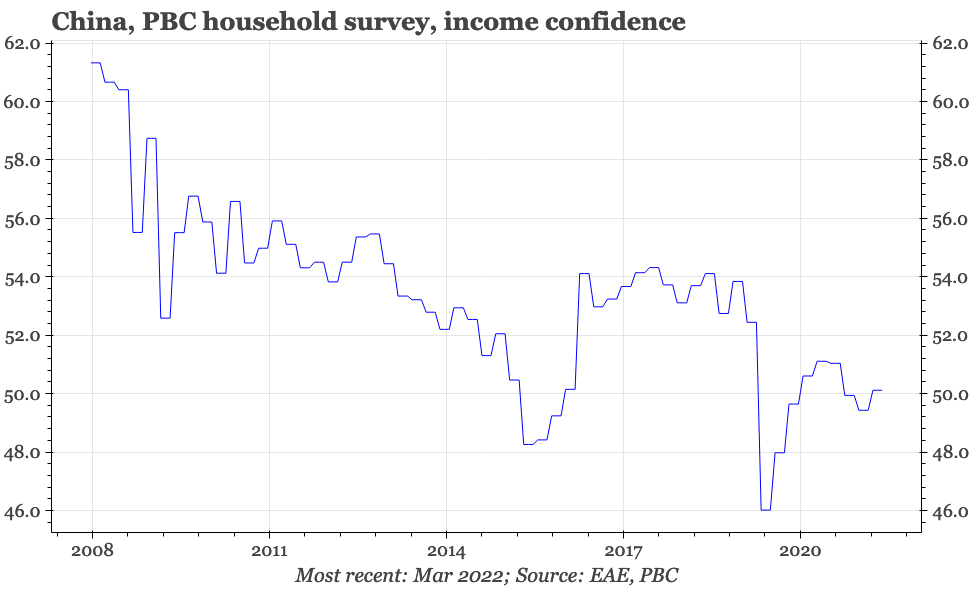

In addition, household income growth slowed during Covid-19, and unlike in many other economies, hasn't bounced since. This step-change down in household income growth reflects government policy, particularly the decision not to offer direct financial aid to families in the way that happened in many of the advanced economies. In a speech give in late April, Li Keqiang offered some insights as to why China hadn't used this approach. The premier argued that such a policy might “look fair and effective, but China is a still a developing country, so it would be difficult to do, wouldn't be possible to sustain, and because levels of regional development and consumption aren't equal, it would lead to unfairness”.

There is evidence that the need to provide greater help to the household sector is being debated. But based on the talk so far, if there is to be any give, it looks likely to be minimal. Prominent local economist and former chief economist of the World Bank, Justin Lin, has called for cash handouts for households, but his proposal is very limited in scope, involving only CNY1,000, and just to families in areas affected by lockdowns. Ex-PBC official Sheng Songcheng, another well-followed and mainstream commentator, continues to advise against any handouts. His view is that some money would end up being saved not spent, and that in any case, it is too tough to overcome the difficulties around the mechanics of distribution.

Frankly, that seems like a smokescreen: if the government wanted to give out money, it is difficulty to think it doesn’t have the bureaucratic capacity to be able to come up with a feasible plan. Instead, the reluctance to go down this path seems to reflect deep-seated, institutionalised views on how China's economy works. Some of these preconceptions come up openly in official discussions, with a common line being that if policy keeps companies in business, then employees will retain their jobs, and households will thus ultimately benefit. Other beliefs are more implicit, with the sense that they exist at all only coming from reading between the lines. As an example, it isn’t hard to think that in China’s one-party system of government, the political pull towards funnelling money towards state-owned enterprises is stronger than giving the same money to individuals.

According to Premier Li, this reluctance to centre policy on helping households doesn’t necessarily mean China needs to go back to its usual policy approach of only favouring investment. In fact, as well as arguing against handouts to households, in his speech he also argued against “just” relying on capex spending, saying that investment evaluations and approvals take time, the desired impact is slow, and it leads to an unscientific and unequal allocation of capital. His preferred third way looks like a version – albeit one with very Chinese characteristics – of “small government”. It was a defence of this vision that was the focus of his recent speech, with highlights being the real corporate tax and fee cuts of recent years, as well as improvements made in the functioning of the government.

In terms of longer-term economic development, these are important, constructive changes. They also seem to have had some impact, particularly in the greater access to credit that smaller firms seem to be enjoying. But on their own, they don’t seem to offer an adequate response to the immediate challenges China faces. Again, activity has slowed sharply recently; property is particularly weak; and income data at least suggests households have yet to see any trickle-down benefit from the tax and fee cuts of the last few years.

Assuming that the government still cares about growth – and I at least think that remains the case – then this all has two implications. First, loosening will likely continue to be mainly in the form of efforts to boost investment via fiscal and monetary easing. (Sheng Songcheng argues that given Fed tightening, monetary loosening is more likely to come first via quantity rather than price). And second, that the policy loosening seen so far isn't yet sufficient to ensure recovery of the economy post the current Covid-19 lockdowns.