China – the CNY and deflationary equilibrium

Deflation looks like 1990s Japan. But China's exchange rate doesn't. Real CNY depreciation helps exports substitute for the weakness of domestic demand in a way that didn't happen in Japan. It also postpones the sort of stimulus that would ease deflation and provide more direction for markets.

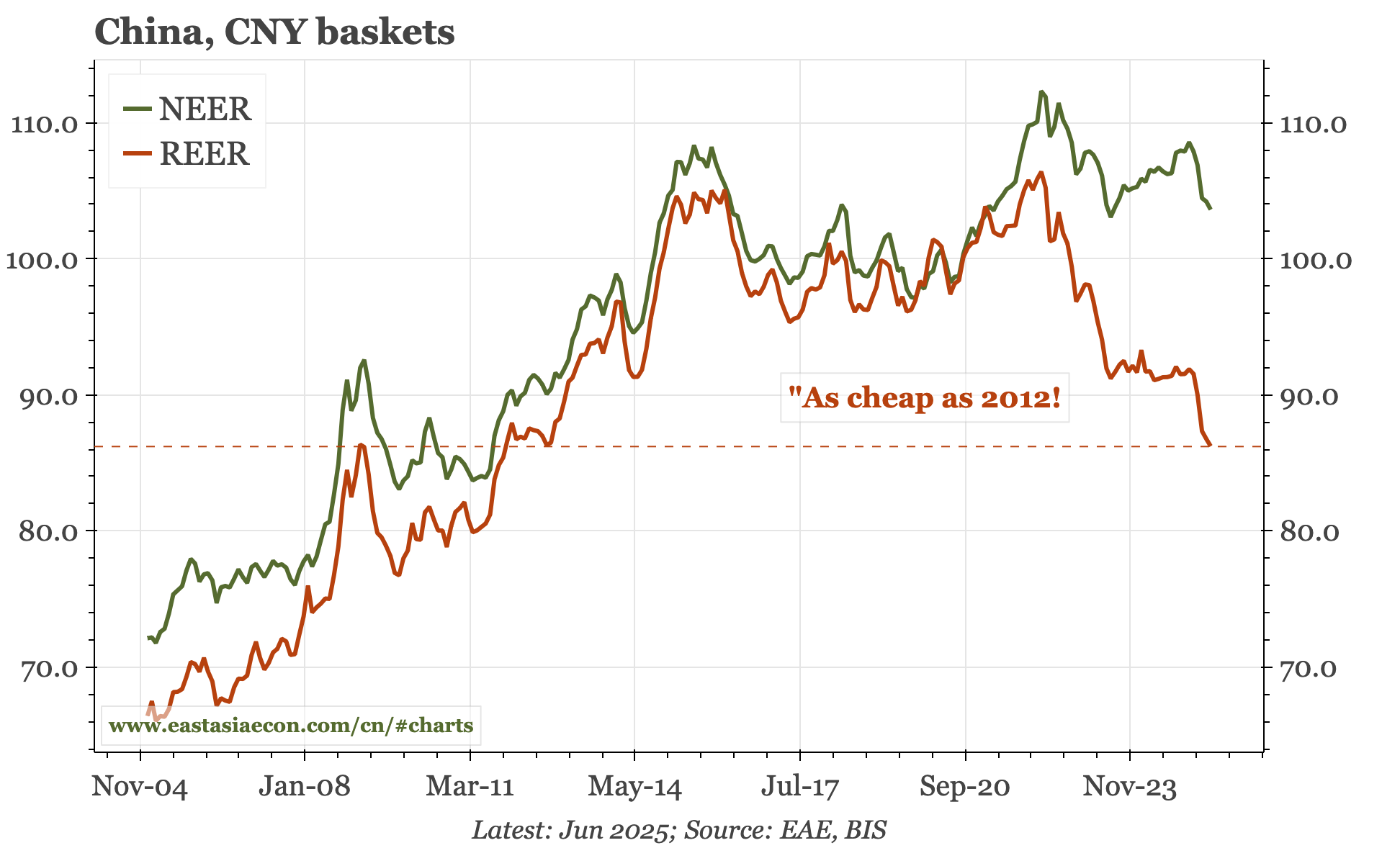

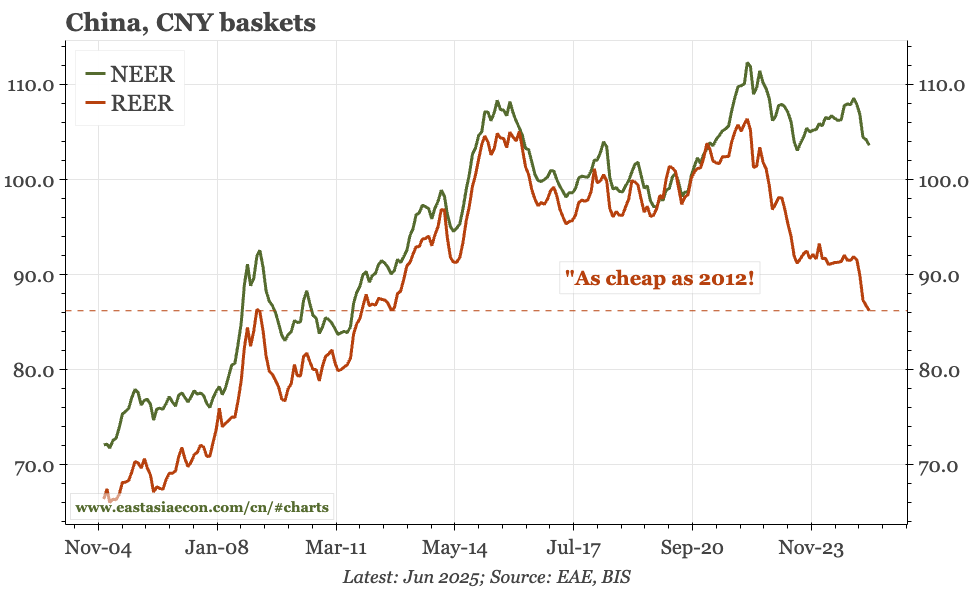

Last week's monthly exchange rate data from the BIS show another decline in the CNY REER in June. It is now down almost 20% from the peak in 2022, and as cheap as any time since 2012. There are other factors at play, but this depreciation of the exchange rate alone has been an important tailwind behind the huge rise in China's global competitiveness. As a reminder, China's global market share has been increasing as quickly in the last 18M as it was in the years after WTO entry in 2001.

This change in the REER clearly hasn't been driven by a weakening of the CNY against the USD. That rate has largely been range bound. As a result, at least until April of this year, the CNY NEER hadn't dropped much, being propped up by the strength of the USD. So, the reason for the weakness of the real CNY is the difference in inflation between China and major trading partners.

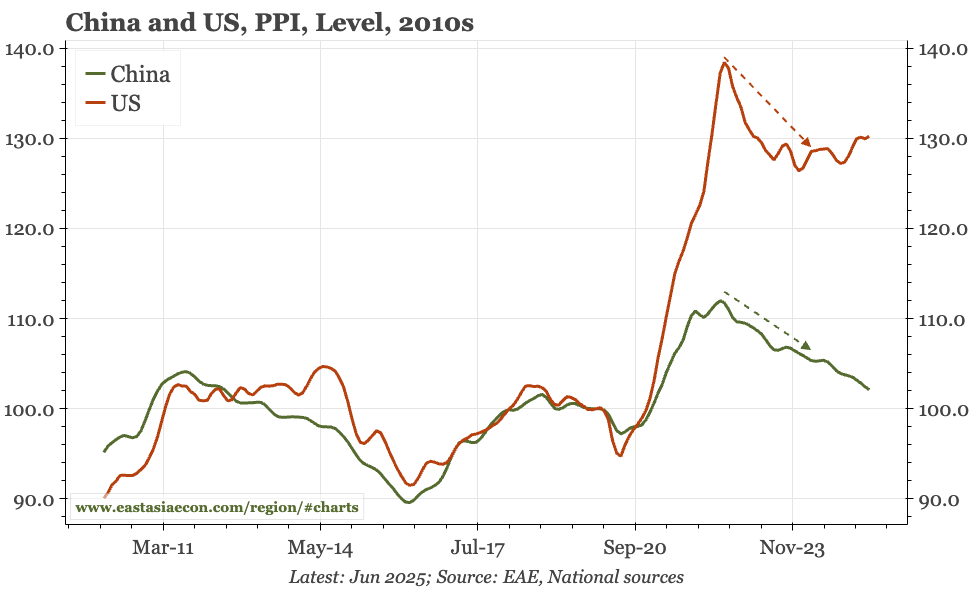

Country-specific rates of inflation are often influenced by global price trends. Usually, that is true for China too, and remained so until recently. Without the aggressive domestic stimulus policies used elsewhere during covid, the ups and downs of the inflation cycle in China during and after the pandemic were more muted than elsewhere, but the directions were similar. In level terms, PPI in both the US and China started to rise from the end of 2020, peaked around the middle of 2022, and then began to fall.

The similarities held until early 2024. From that time, PPI in the US started to stabilise. In China, by contrast, it continued to fall. PPI in the US is now the same level as in early 2023. In China, it is 7% lower.

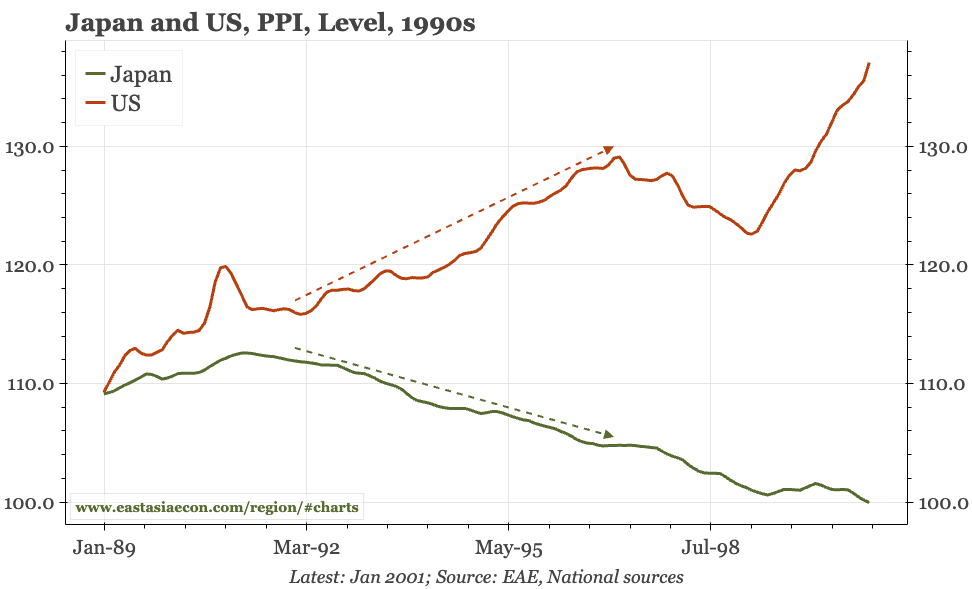

With that break appearing, China in terms of prices is starting to look more similar to Japan in the 1990s. The gap that then appeared between PPI in the US which was rising while falling in Japan was a harbinger of the country-specific deflation that Japan would go on to experience for much of the next years 30 years; in that first episode of deflation alone, PPI in Japan fell YoY for all but seven months until 2004.

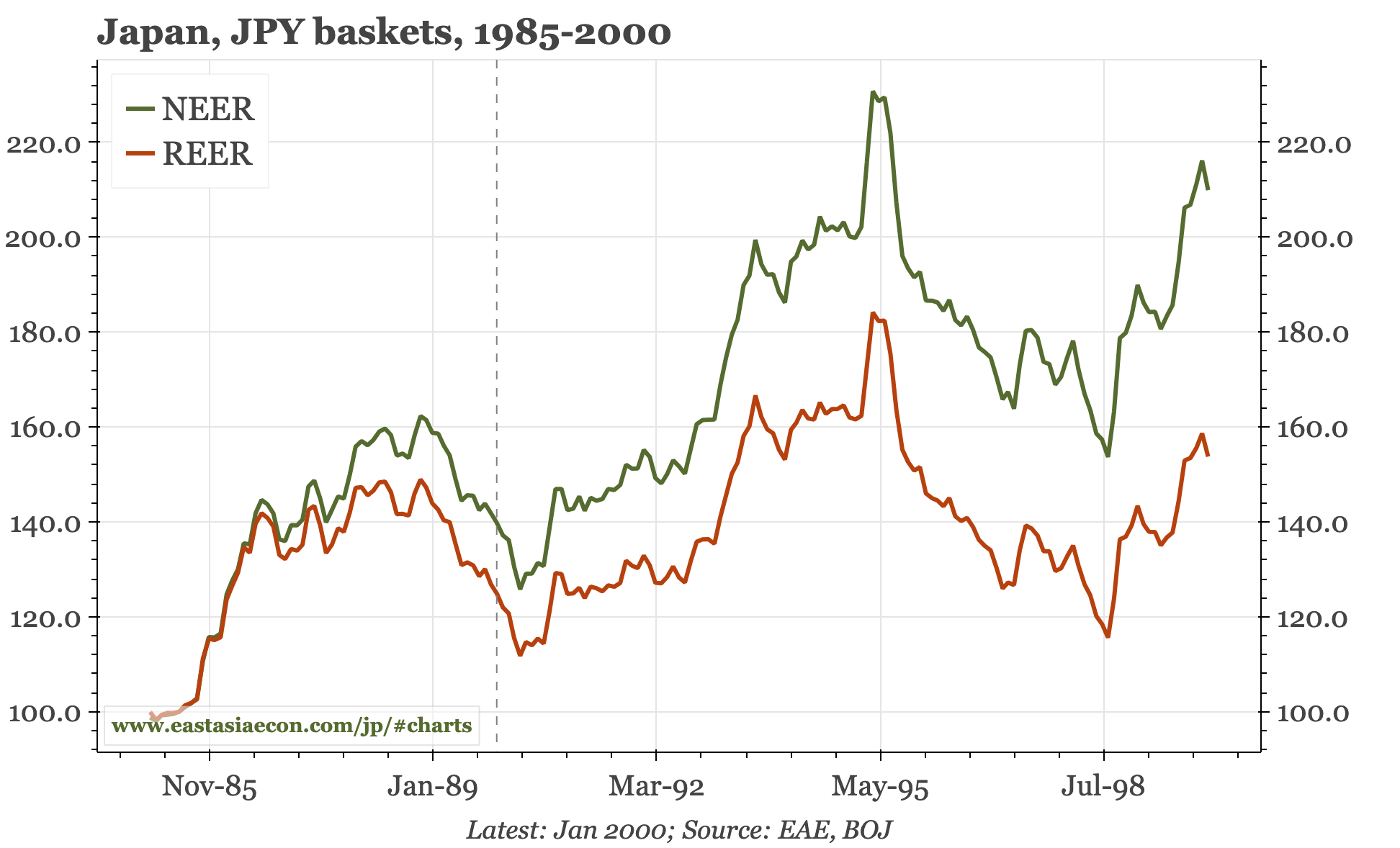

However, while there are similarities in price trends, the exchange rate experience couldn't be more different between Japan then and China now. After the big appreciation of the 1990s, the nominal JPY kept rising in the 1990s. That rise offset the boost to Japan's competitiveness that otherwise would have been the result of the emergence of deflation – the 65% rise in the JPY NEER more than cancelled out the impact of Japan's falling price level, with the JPY REER also rising by almost 50%. By further tightening monetary conditions, it also reinforced the deflation that Japan was beginning to suffer.

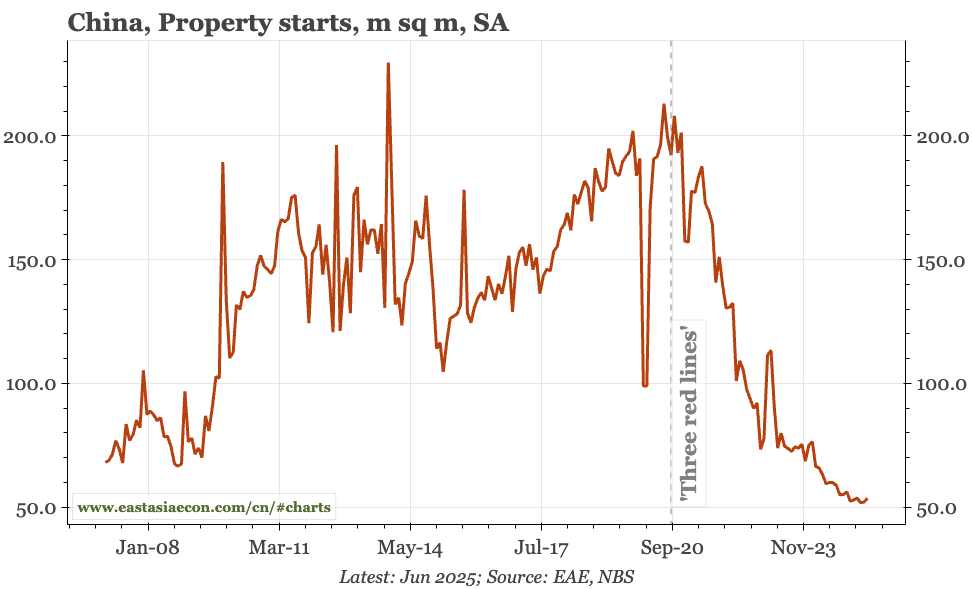

Back to today, and policymakers in China have recently started to focus on deflation, stepping up criticism of "corporate involution", excessive competition and price cuts. These supply-side dynamics are undoubtedly part of China's deflation story. But so is weak domestic demand, as shown most obviously by the weakness in property market activity, the decline in construction, and the fall in building materials prices.

The latest upstream price data released today for the last 10 days of July show some respite in that trend at the end of last month, but no real rebound. Building material prices – cement and glass – are now 20% lower than the last peak in late 2024, and a full 60% below the covid peak of 2021. That is important given cement in particular was a big target of the supply-side reform of 2015-16, the last big initiative aimed at controlling corporate over-capacity.

So, the weakness of aggregate demand is a real issue. But it is important that, unlike Japan in the 1990s, that weakness isn't being exacerbated by currency appreciation. While the JPY rose by double-digits in the five years after the bubble burst in 1989, since China's government declared the "three red lines" for the property market in 2021, the CNY has been stable in nominal terms, and weak after accounting for inflation.

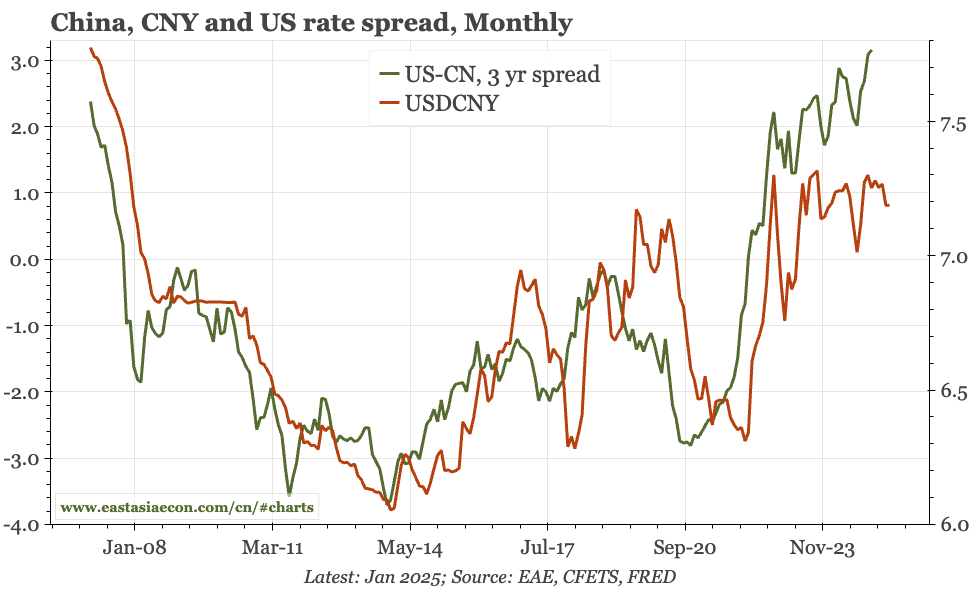

Probably, it would be beneficial for China's domestic economy if the currency was weaker still. At least until the USD began to soften from April, there was a lot of evidence that the PBC was leaning against depreciation. That was most likely partly out of fear of exacerbating capital outflows, and also perhaps the desire in Beijing to establish the CNY as a source of stability as US economic policy became increasingly uncertain. Even now, interest rate differentials suggest a $CNY exchange rate of around 7.5. Without nominal depreciation, the exchange rate doesn't provide a lift to inflation via import prices.

That said, it isn't clear that the most natural direction for $CNY is upwards. China's very evident export competitiveness – reflected in its global market share and rising trade surplus – is one factor that, if anything, supports CNY strength. With inflation falling so much, real interest rate differentials would probably also suggest that the CNY should be strengthening.

The rise in real rates was, I think, part of the explanation for the strength of the JPY in the first half of the 1990s. But Japan also lacks China's capital controls – and, 30 years ago, any sense of urgency to counter the rise in the JPY, with little realisation of the true extent of the economic correction that Japan was facing. So, the authorities in Tokyo then had neither the will nor the tools to stop the JPY from appreciating.

China obviously now has Japan's experience of the 1990s to learn from. With the ongoing problems in the property market, it is easy to argue that China's learning has been insufficient. Still, at least in terms of the exchange rate, China isn't repeating the mistakes of Japan. That the exchange rate is not strengthening allows the decline in domestic prices to feed into CNY depreciation in real terms, which in turn boosts export competitiveness and so external demand.

In this way, the exchange rate continues to act as a stabiliser for the macro economy. As such, it helps explain why policymakers haven't been more active in offering policy stimulus. However, it also leaves the economy in a something like a deflationary equilibrium, which in turn is why onshore risk appetite has struggled to lift.

I doubt supply-side policies aimed at tackling corporate involution will alone change this situation. By cutting off external demand and so forcing domestic stimulus, tariffs might. But an exchange rate that in real terms is as cheap as 13 years ago buys the authorities some time, and last week's Politburo statement gave little indication that Beijing sees much more urgency to boost aggregate demand.