China – another dawn

Does anti-involution produce macro turnaround when the September combination of stock market and local government bail-out failed? The markets are hopeful. I am more cautious, given China's macro problems are weak demand as well as strong supply. I'd be wrong if household savings behaviour shifts.

The blitz of policy announcements that began in September last year triggered some market excitement that China's cycle was about to turn. Now there is another wave of expectation, as the government steps up criticism of supply-side excesses.

I was sceptical of macro turnaround in September, and I am doubtful this time too. That's not because the idea of over-investment and a resultant lack of pricing power being drivers of weak inflation and profits is misplaced. Rather, it is because of all the evidence showing that weak aggregate demand resulting from the collapse in property market activity – a trend that has yet to reverse – has also played a role.

There aren't signs recently that more policy effort is being made to boost demand. In fact, it could well be the opposite: if corporate investment is now curtailed, it will dampen one of the few areas of spending that has increased since 2021 and so helped fill in the hole in demand left by the drop in real estate.

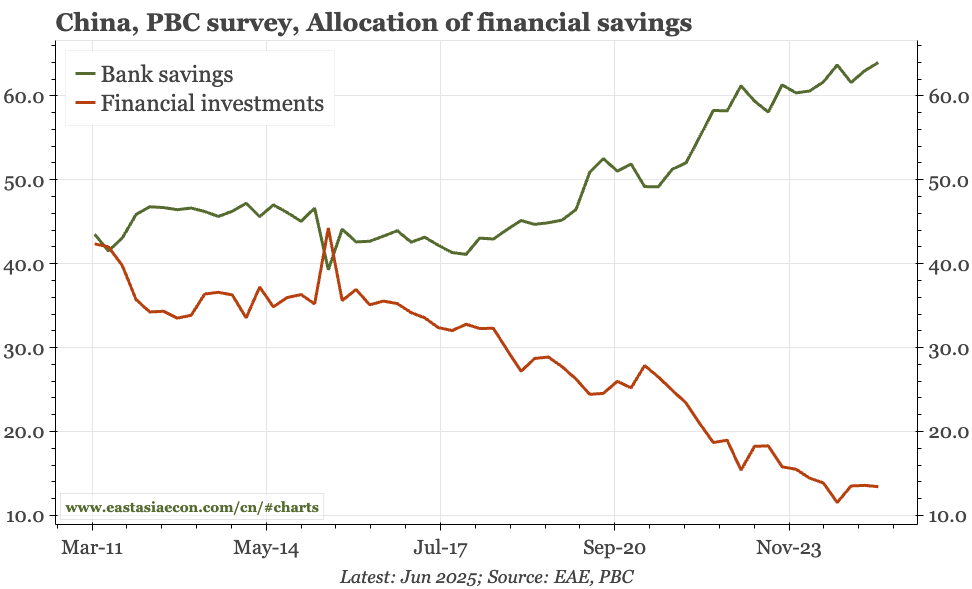

In September, I could see one path by which policy would have fed into a bigger macro turnaround: that government attempts to boost equity prices would pull money out of time deposits, boosting M1 and thus inflation. That didn't happen. However, it is the upside risk this time too. While in itself not a great macro story, the anti-involution effort should be good for equities. With the weakness of the USD boosting Hong Kong asset prices, onshore equities this time also have the tailwind of a widening A-H discount.

So, I'd continue to watch household deposit trends. But a turn wouldn't be my base case, with the PBC's quarterly sentiment surveys at the weekend continuing to show the household sector remaining very cautious. My base case would be this time, like September, is a false dawn for macro.

Does anti-involution work when the September combination of stock market and local government bail-out failed? The markets are hopeful that it does.

While the level of official angst about excessive competition and price-cutting has been rising for a while, it became much more important for investors when particularly direct comments from Xi Jinping were carried on the front page of the People's Daily:

When it comes to projects, there are a few things – AI, computing power and new energy vehicles. Do all provinces in the country have to develop industries in these directions?

Encouraged by these comments, onshore equities have rallied to the highest levels since early October. CGB yields have also risen. After resisting pressure for the CNY to depreciate, it now looks like the PBC is trying to stop the exchange rate from strengthening.

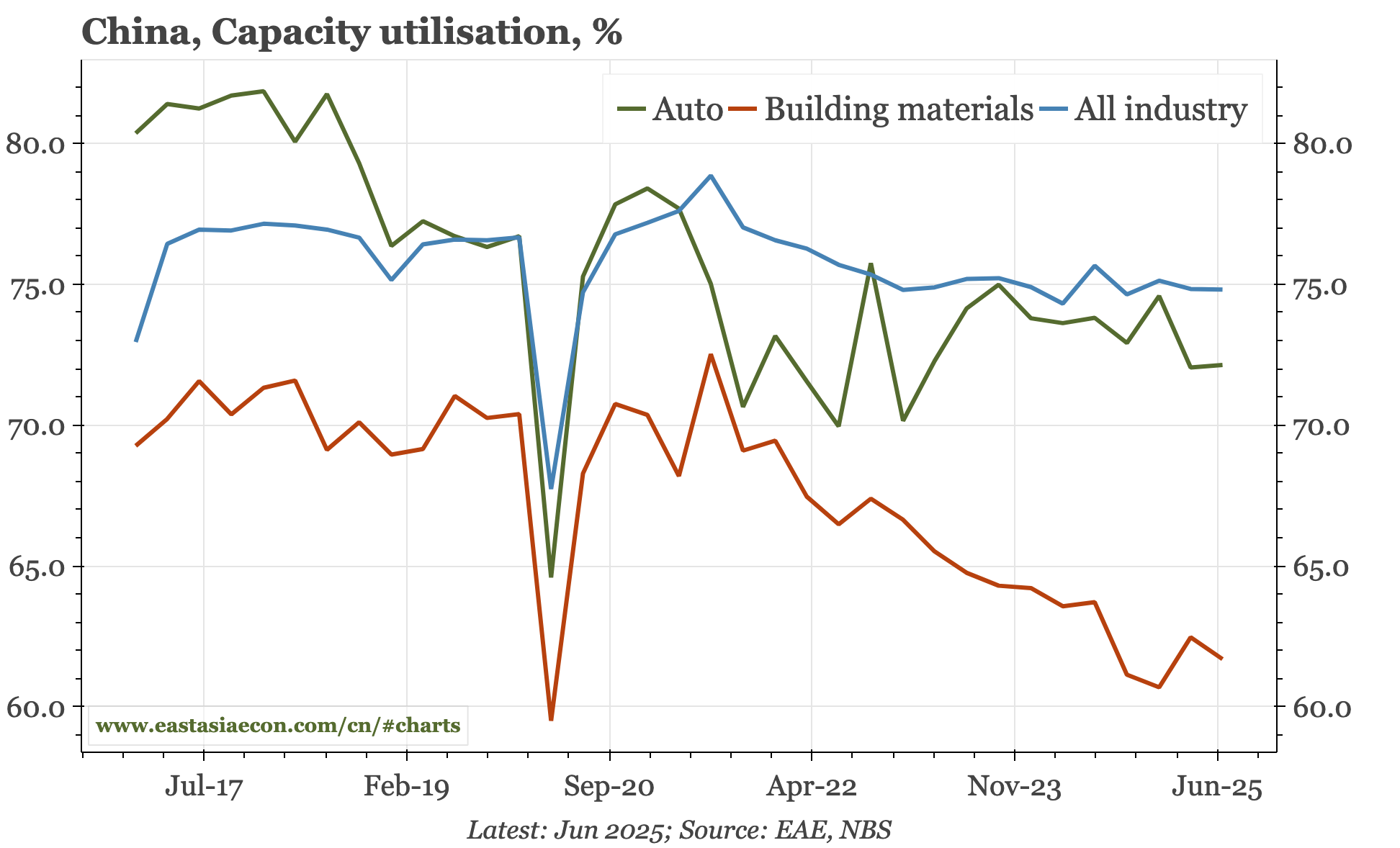

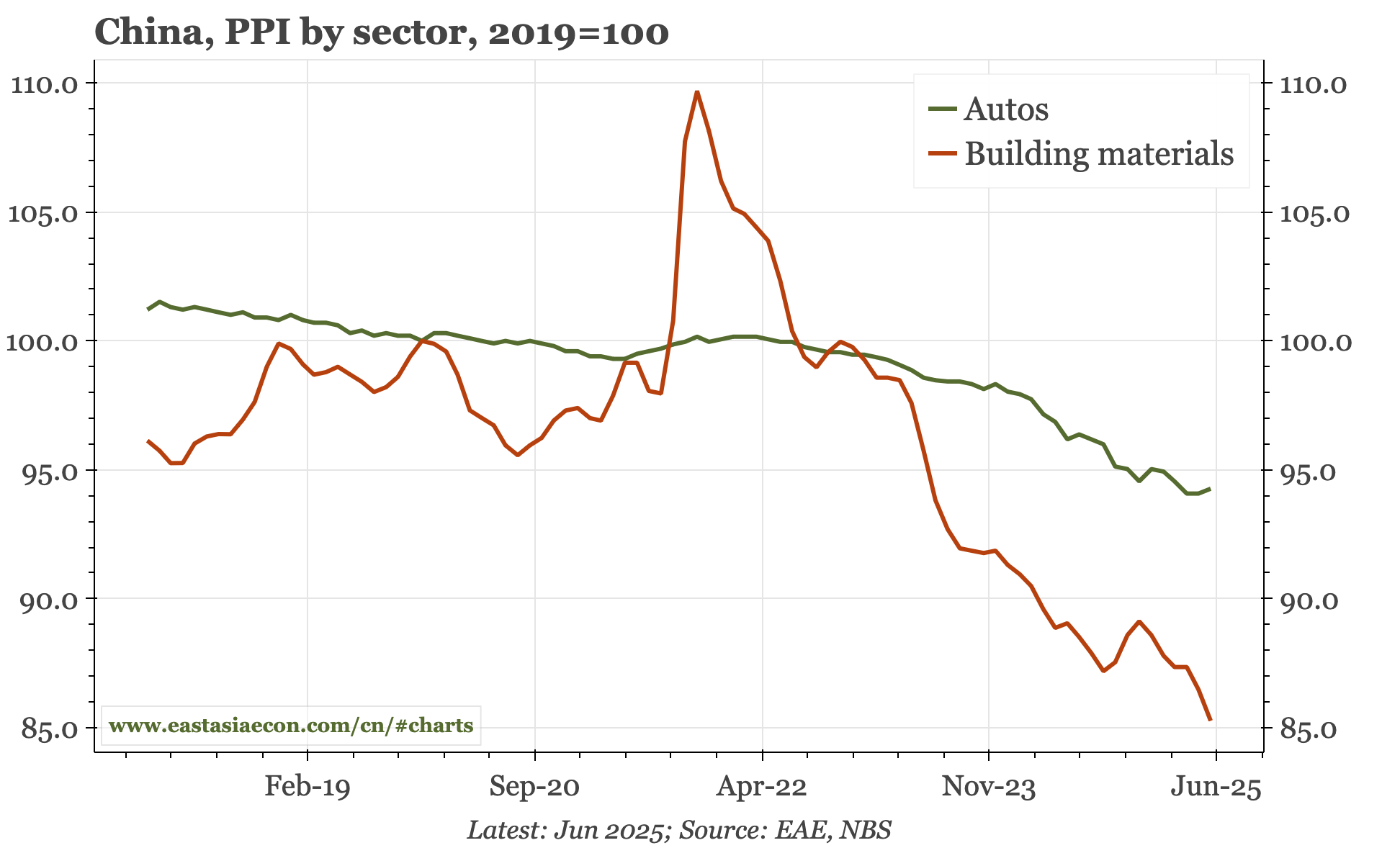

That some optimism exists is understandable. Excessive investment and falling prices in manufacturing have been clear problems. In the auto industry, to use a prominent example, capacity utilisation is lower than any time in the last 10 years (excluding the covid crises), and factory-gate price since 2020 have fallen particularly sharply. If there is action to reduce capacity, it will certainly be important for companies in these sectors.

By extension, then, this could well be a big deal for the equity market. That's particularly true for onshore indices, given they have failed to keep pace with the big rally in Hong Kong of recent weeks– meaning the A-H discount has blown out.

But I am not convinced it matters as much for the overall economy and so the level of rates. Rather than being purely a micro phenomenon, deflation is also in large part being driven by a deficiency of aggregate demand, a drop that's happened on the back of the collapse in property market activity.

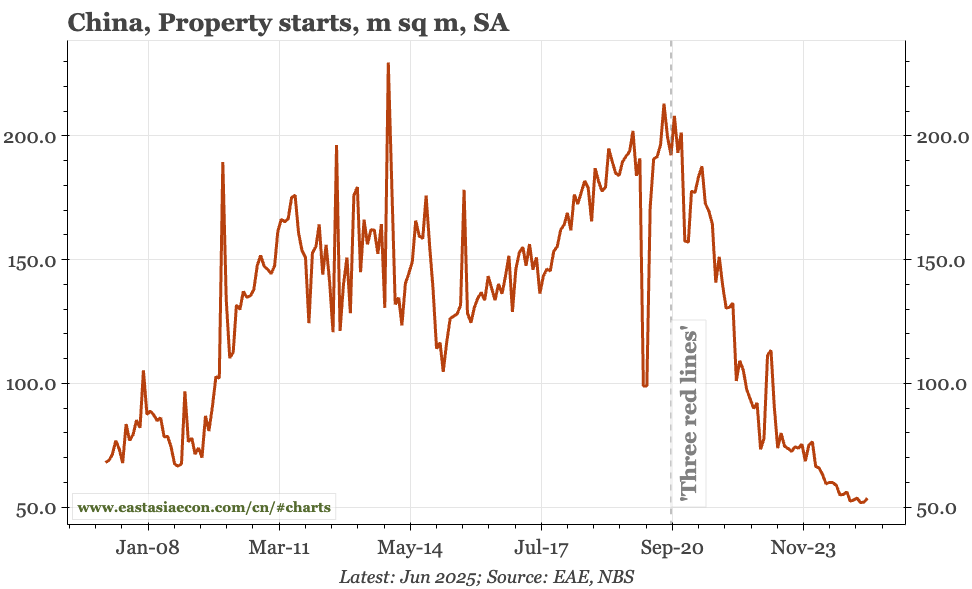

The continuing weakness in real estate can be seen across a whole range of indicators – housing starts at the lowest level in 20 years, mortgage lending similarly depressed, and in the latest GDP release, a renewed contraction in overall construction.

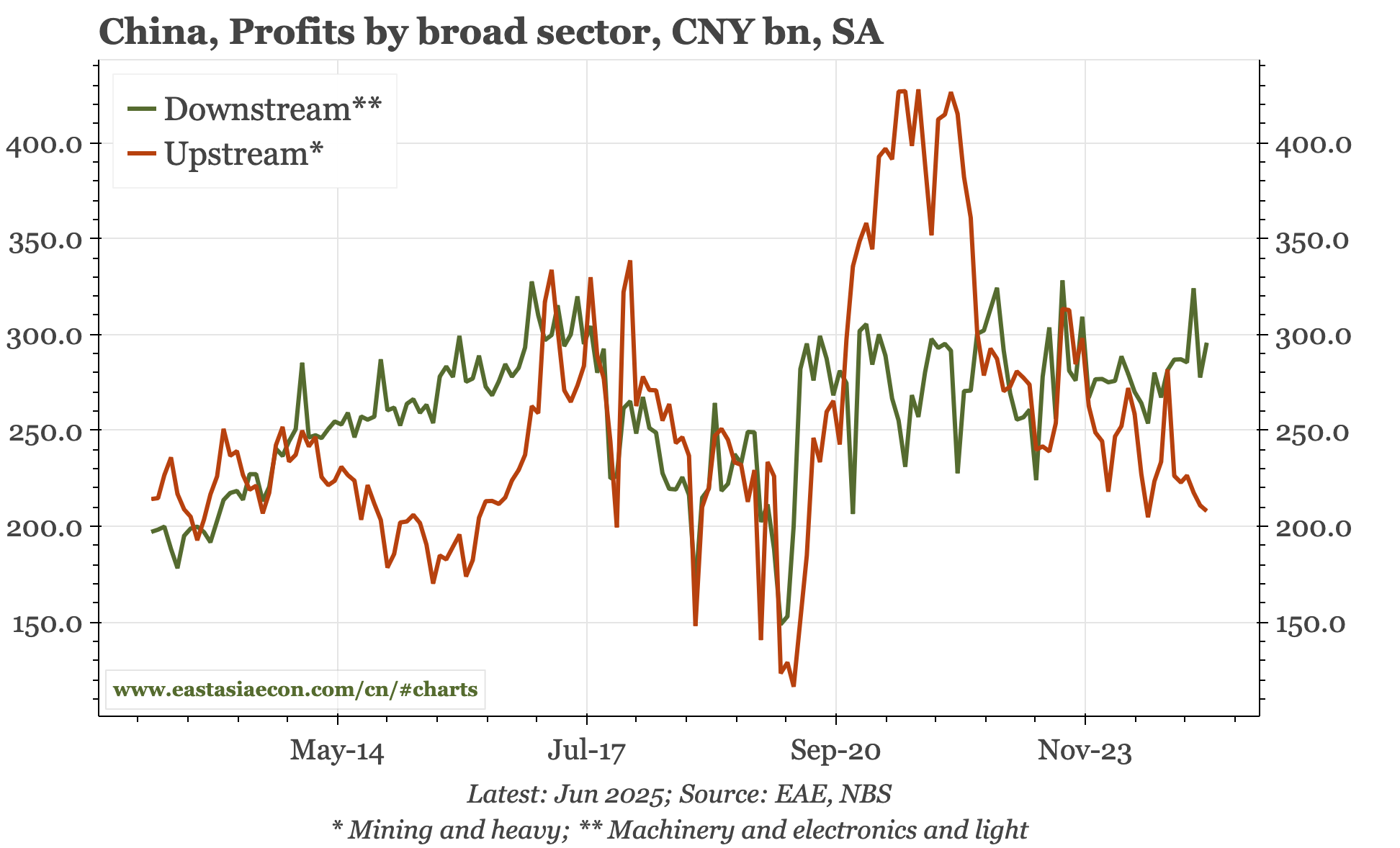

The direct, ongoing pain caused by the sudden stop in real estate can in turn be seen directly in price data, with building material prices continuing to fall sharply. It can also be seen in profits data, where the weakest sectors aren't manufacturing but rather mining and heavy industry.

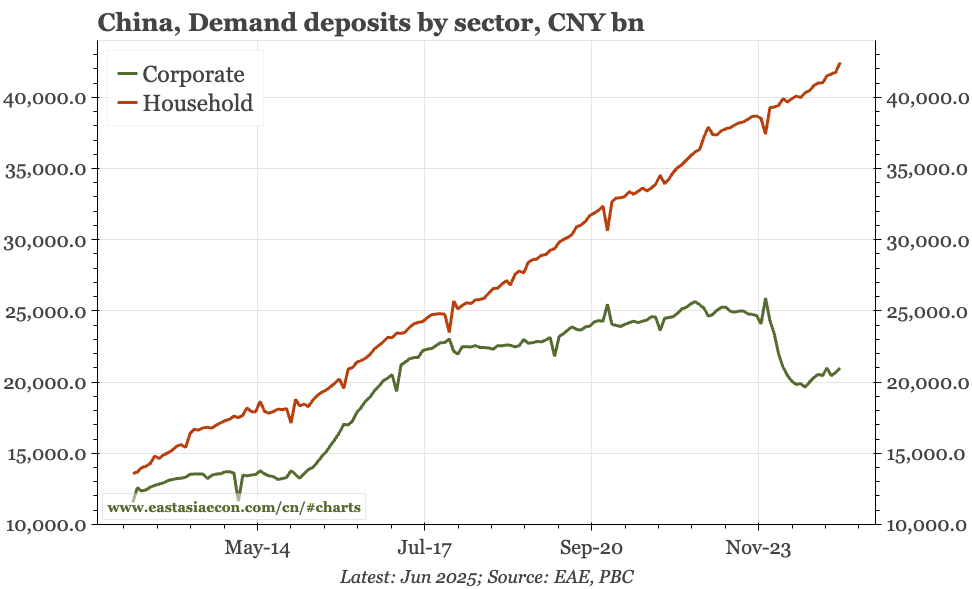

The collapse in property also affects inflation indirectly. The release this weekend of the PBC's household surveys for 1H25 showed again that the biggest change in consumer behaviour since covid isn't a rise in savings, but a change in the type of savings. No longer investing in property – or indeed riskier financial investments – household savings have instead increasingly shown up as bank accounts, particularly in the form of time deposits. The resultant decline in the proportion of savings held in demand deposits has tended to be a good leading indicator for inflation.

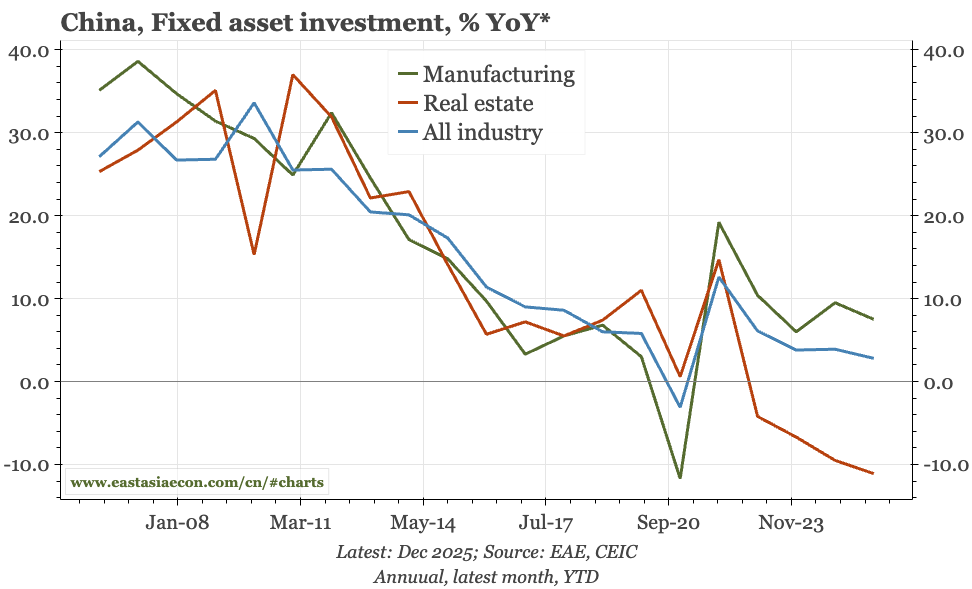

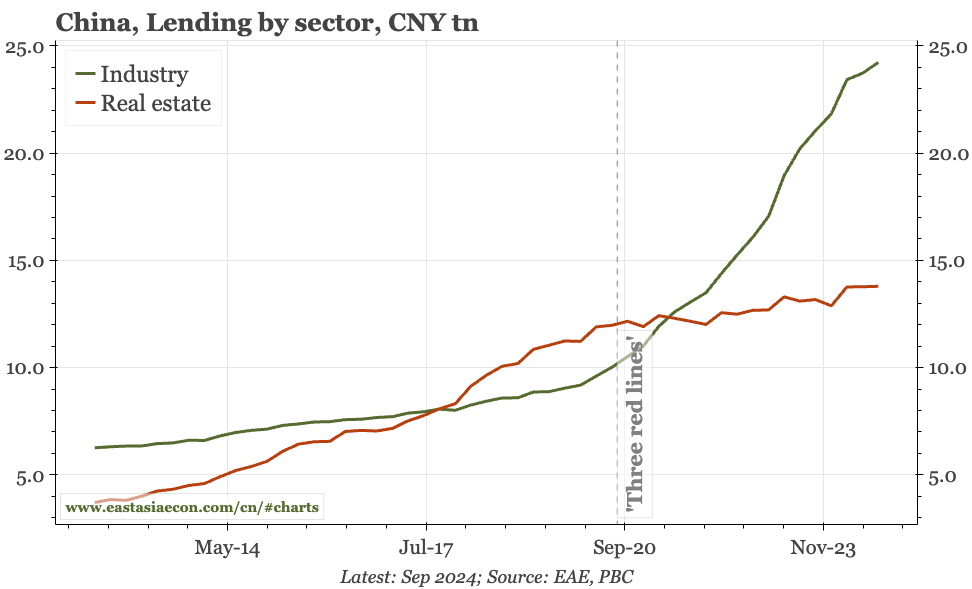

In terms of aggregate demand, the one offset to the weakness in real estate has been the spending on manufacturing capacity that the government is now complaining about. While investment in property has fallen 10% this year, capex in manufacturing has risen by almost as much. Similarly, borrowing by industry has helped fill the gap for banks created by the fall-off in lending to real estate.

Until now, the government has thought of the strength of investment in the industries highlighted by Xi as a phenomenon to be welcomed. Investments in these sectors is consistent with the CCP's goals of self-sufficiency and promotion of "new quality productive forces". As such, trends in favoured manufacturing sectors are almost always specially highlighted in the government's monthly economic summary, with officials noting in June that

output of 3D printing equipment, new energy vehicles, and industrial robots increased by 43.1%, 36.2%, and 35.6% YoY respectively....Private investment decreased by 0.6% YoY; excluding real estate development investment, other private investment increased by 5.1%. In high-tech industries, investment in information services, aerospace equipment manufacturing, and computer and office equipmy ent manufacturing increased by 37.4%, 26.3%, and 21.5% YoY.

The government won't be abandoning its big-picture goals of reducing dependence on the west, and in industries like semiconductors where China is still a distance behind, nor will sector-specific promotion be rolled back. However, in other industries like electric vehicles, officials are probably now feeling that China is not just securely self-sufficient, but actually holds an unassailable lead. As a result, the authorities can start to rein in the excesses.

This might well have an impact on the demand-supply balance at the industry level. But for that to be sustained, investment in future capacity will have to be restrained. That will be a problem for the macroeconomy, given it is only this investment spending – and the feed through into exports – that has been offsetting the impact of the collapse in the property market. If the government really is serious about tackling corporate involution then, the impact will likely be less aggregate demand that actually keeps inflation low, and a fall in investment that widens the S-I gap and thus the current account surplus.

So my base case would be this time, like September, is a false dawn. However, like then, I can see some upside risk, in the form of an equity market rally that is strong enough to drag household money out of fixed deposits and back into current accounts. That would boost M1 and thus have the potential to also raise inflation.

It is the household sector I think that holds the key, and not just because of the very real shifts in savings behaviour caused by the sudden stop in real estate. It is also because corporate savings data have been distorted by regulatory changes last year. A normalisation from those is one reason M1 has bounced in recent months. Household deposits weren't affected by the same distortions, and so it is more significant for macro that household demand deposits haven't yet shown a trend change.