Japan – inflation risks skewed to the upside

Today's shunto 2025 results are constructive, but not a game changer. Upside risks from other dynamics are bigger: part-time wages, the output gap, inflation expectations, processed food prices, rent, and pent-up inflation pressure in both PPI and public services prices.

Downside

Fresh food

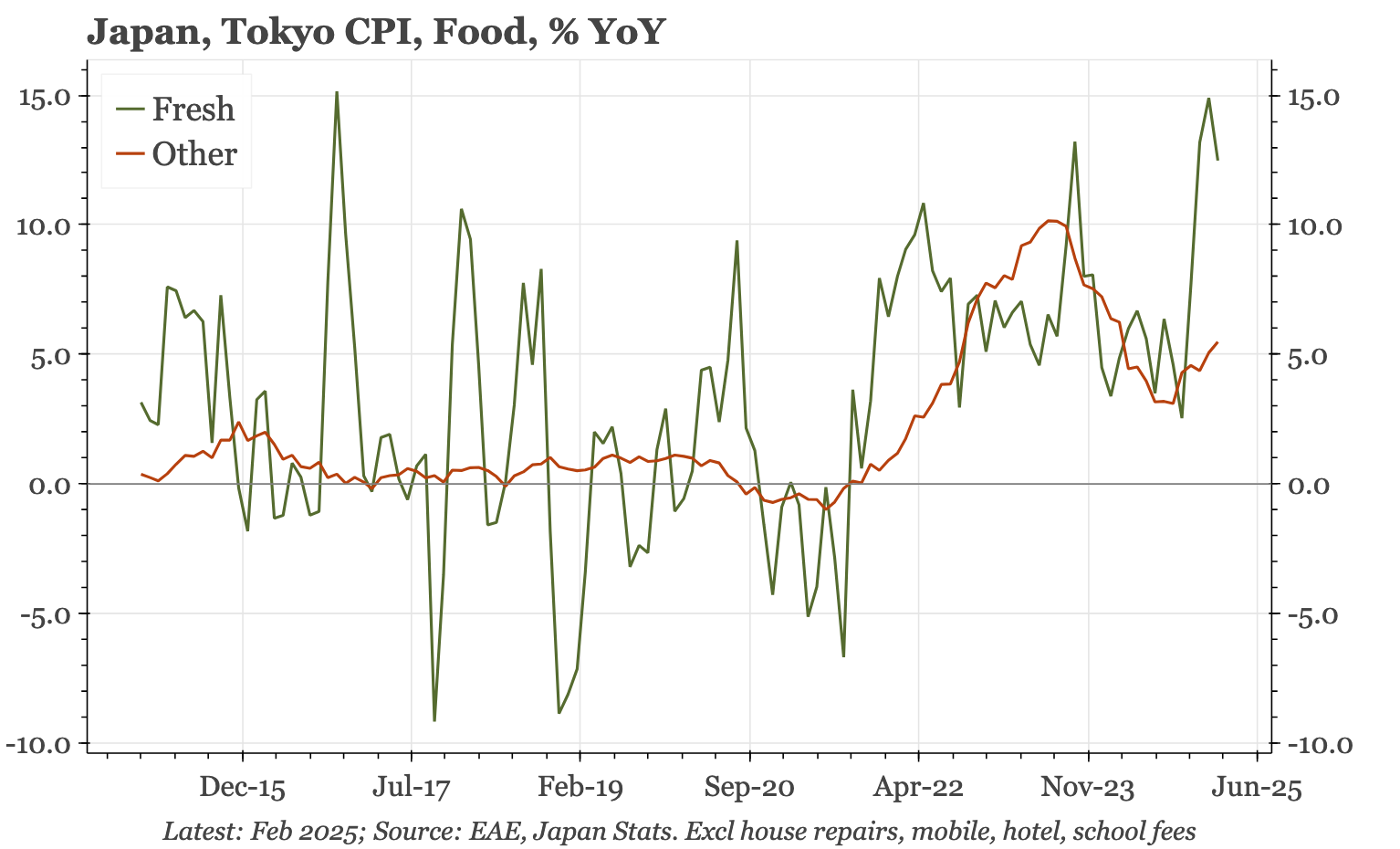

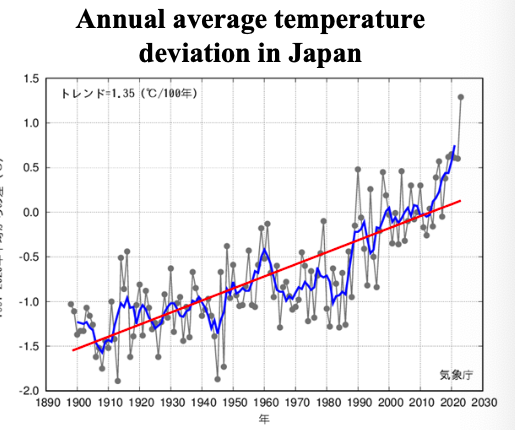

Fresh food prices, which have a 4% weighting in the CPI basket, have been surging, with cabbage prices more than doubling in the last year. The 70% rise in the price of rice (0.6% weighting) has been even more eye-catching. These prices are likely to fall back. Fresh food prices are by their nature volatile, being dependent on local weather conditions. The government has been releasing stockpiles to try to bring rice prices down. The worsening climate may mean that on average, fresh food prices are higher than they used to be, but in the short-term, a fall-back in inflation is more likely.

Balanced

Service prices

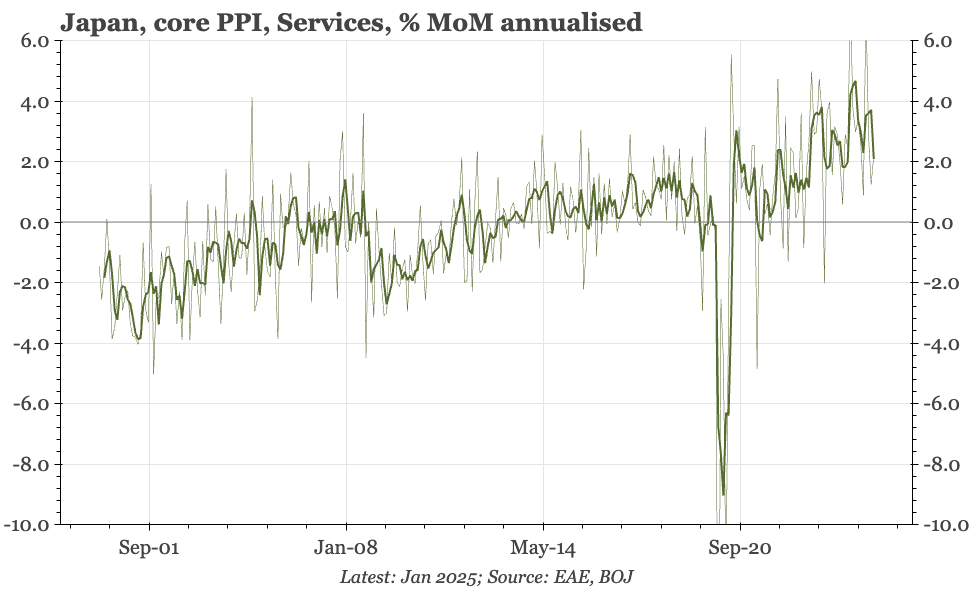

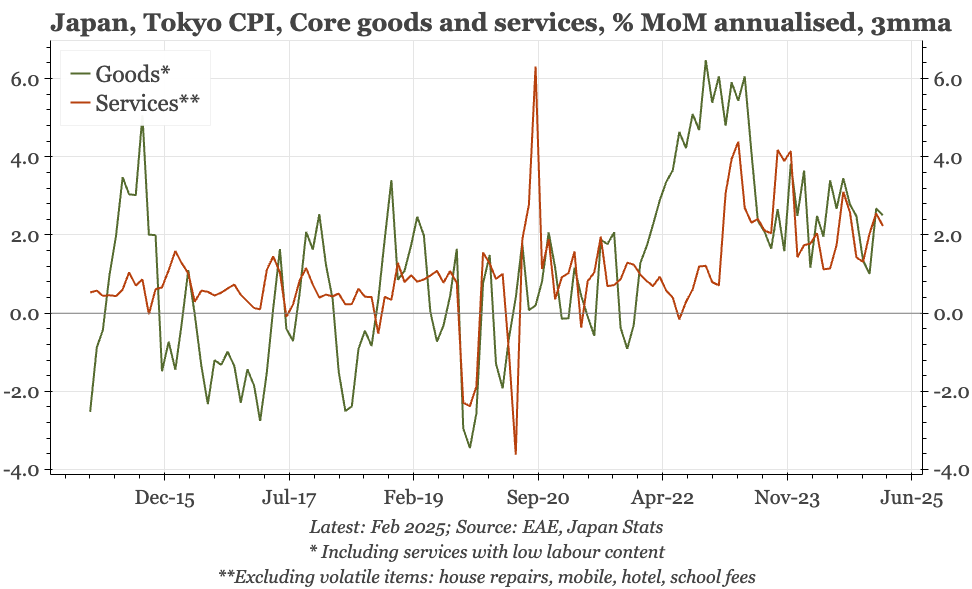

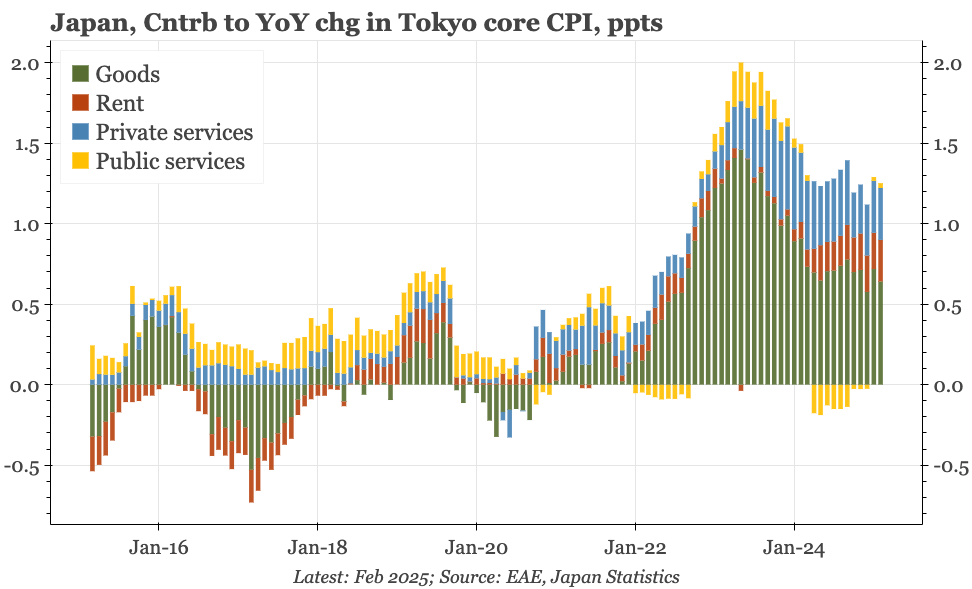

Price inflation in both upstream services PPI and downstream core private services CPI is running at around 2% annualised. For both, these are rates of inflation that haven't been seen for decades. Neither are yet showing signs of accelerating further. Given the upside risks to inflation, that should start to change.

Upside

Output gap

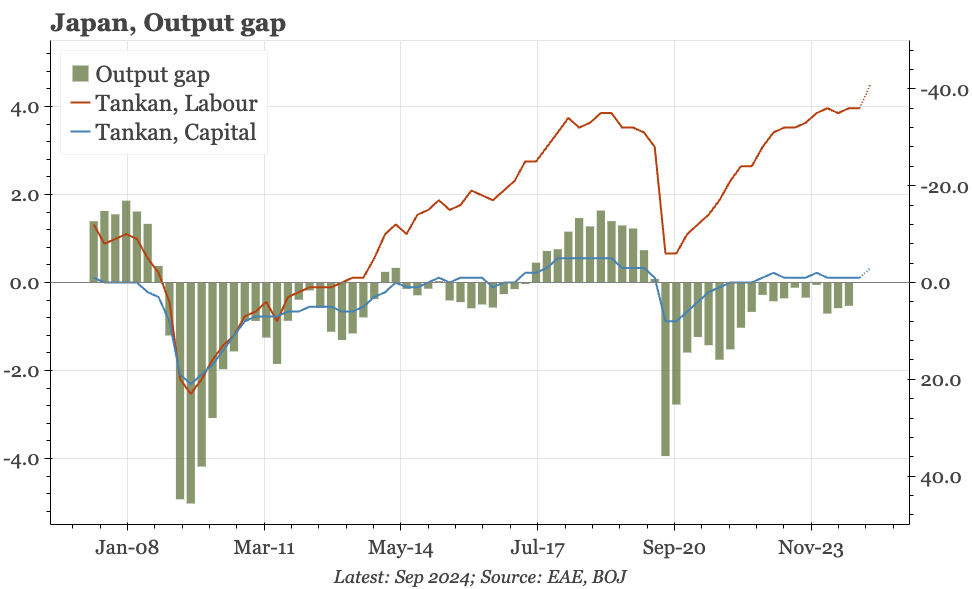

One statistic arguing against higher inflation is the negative output gap. That's a function of extreme labour market tightness – which on its own suggests the output gap closed a long time ago – being offset by the ongoing low level of capacity utilisation. Since the beginning of this year, the bank seems to have embraced the view that capacity utilisation is understated, with its measurement skewed by the very tightness of the labour market. As explained by deputy governor Uchida in a speech this month:

hotels and Japanese-style inns across the country have noted that they have to turn down reservations despite having rooms available because they cannot find enough staff.

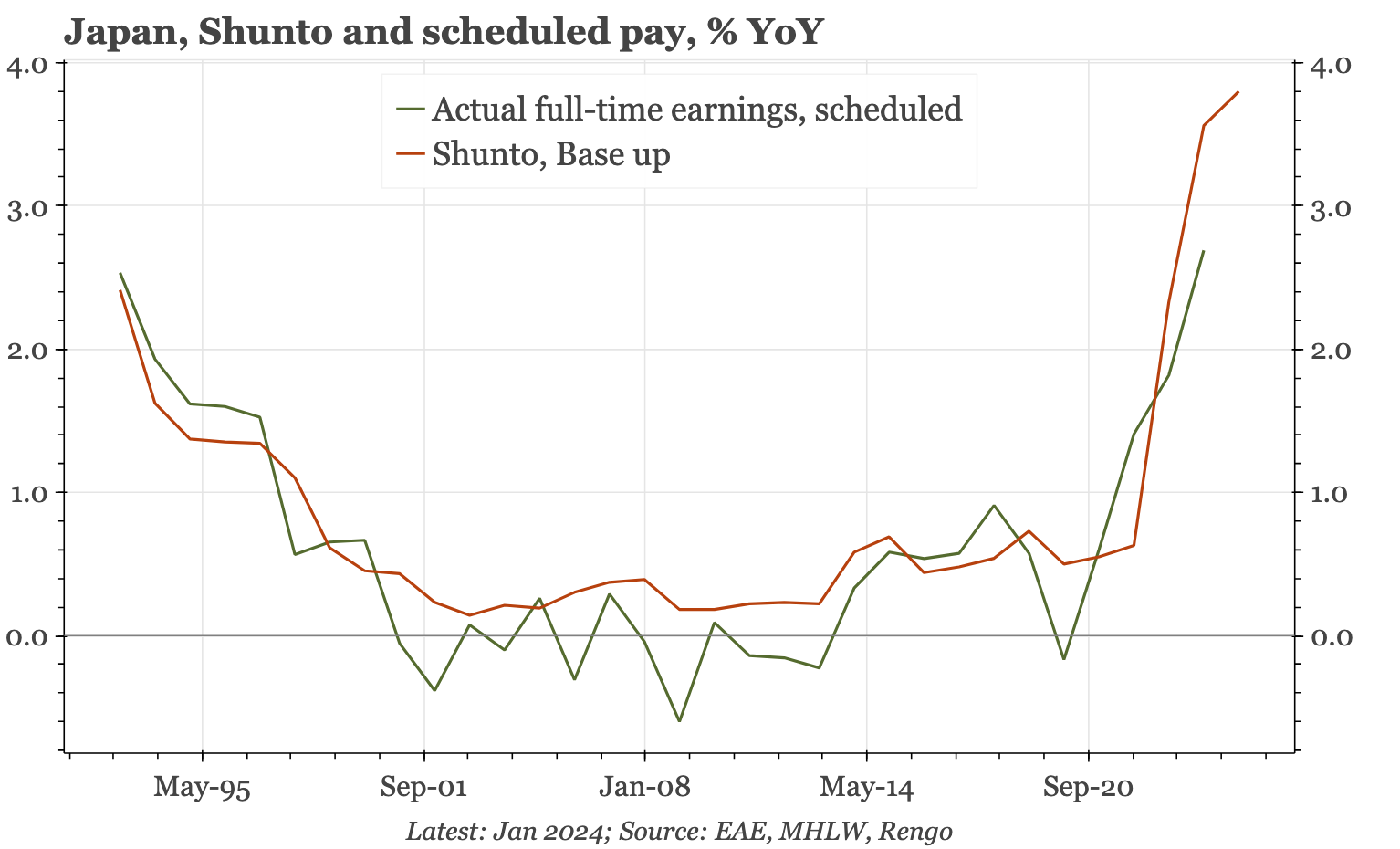

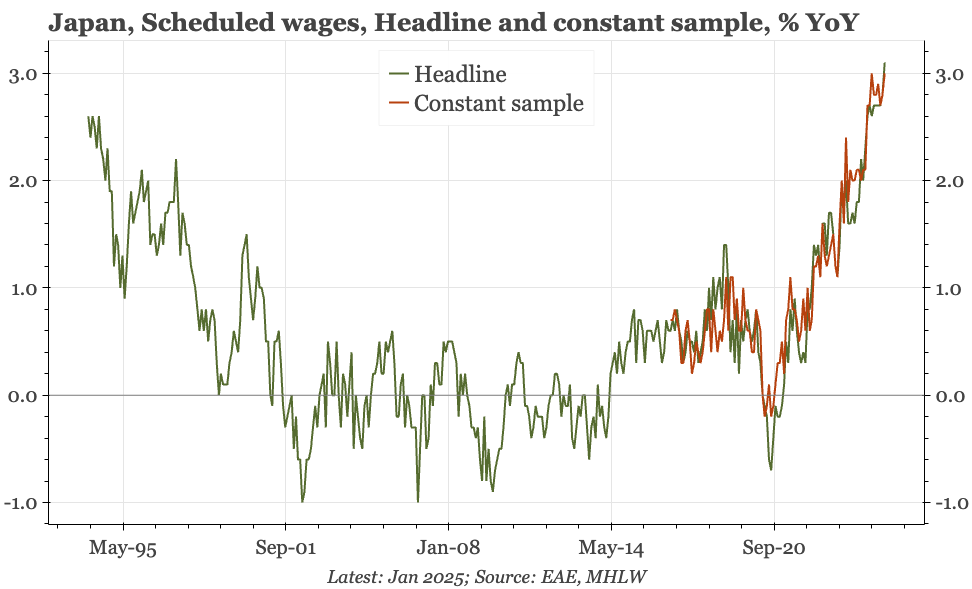

Regular wages

According to today's preliminary results of the 2025 shunto, wages at large firms will rise by 5.5% this year. The read-through from that into actual wages isn't direct. The shunto result includes a seniority increment, and excluding that, it looks like base wages will rise around 3.8%, up from 3.6% in 2024. Actual monthly wage data show result worker wages rising by a bit less than 3% last year. So, with some catch-up and the further rise in this year's shunto, regular wage growth should accelerate further this year, That is constructive, but it isn't a game-changer.

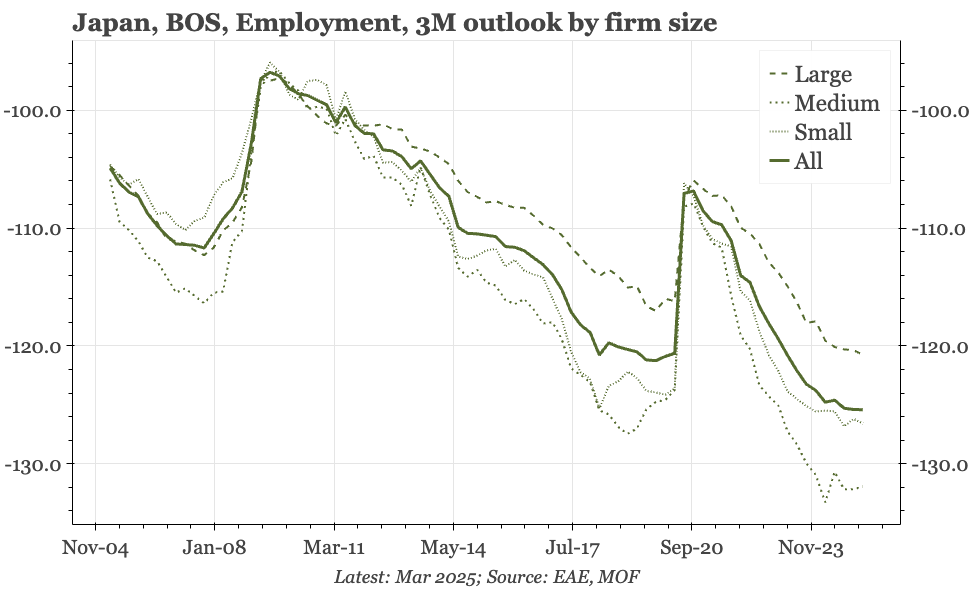

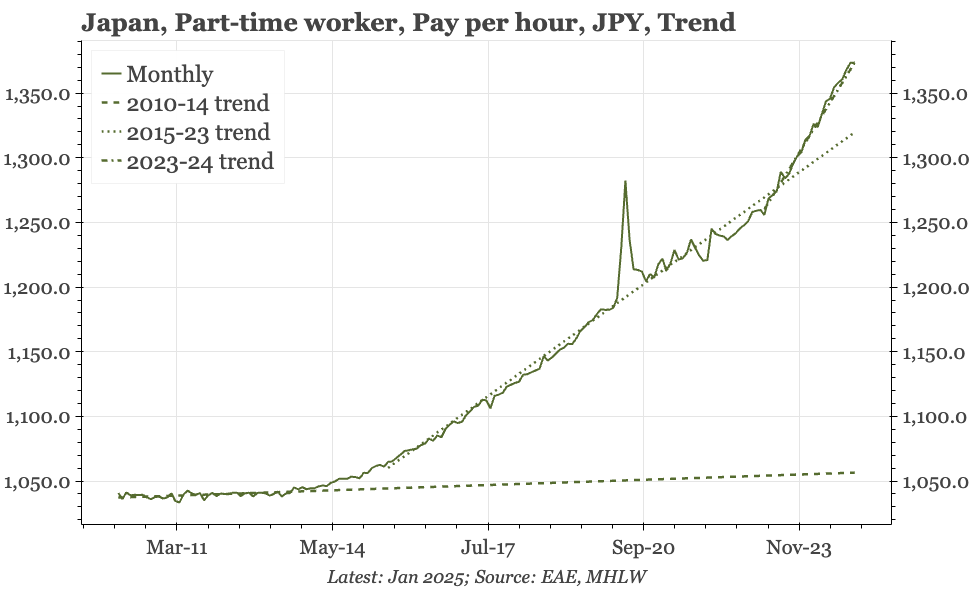

Part-time earnings

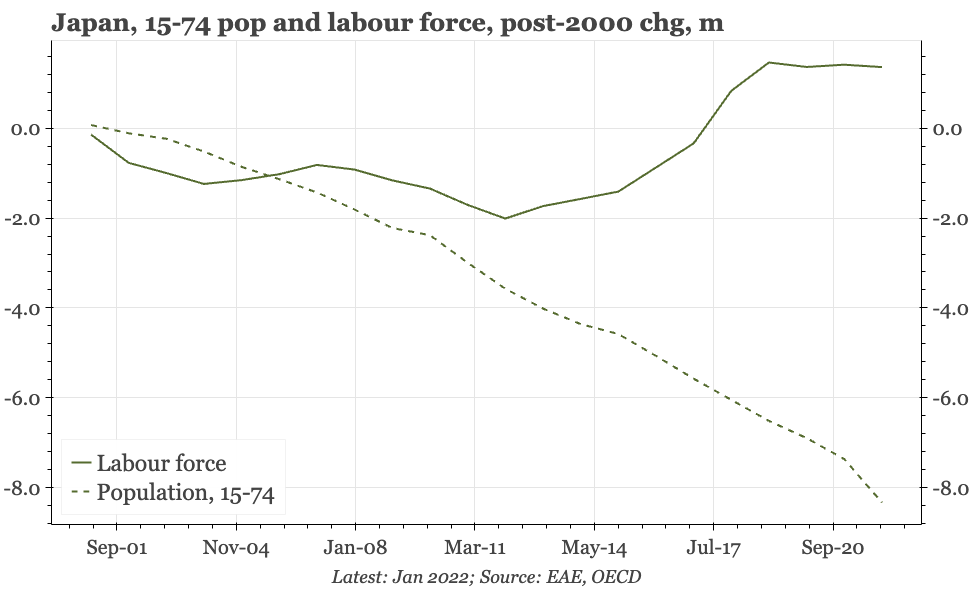

Part-time workers enjoy much less protection than their full-time, regular counterparts. When the labour market was slack, that meant part-timers were the cheap – and so favoured – choice of many employers. However, being more driven by underlying demand-supply dynamics, labour market tightness is now generating faster wage inflation for part-time workers. That's already up to 4.5%, There is the prospect of another squeeze higher if the BOJ is right and the sharp rise in the participation rate, a phenomenon that has dulled the impact on labour supply of Japan's terrible demographics, is close to a structural peak.

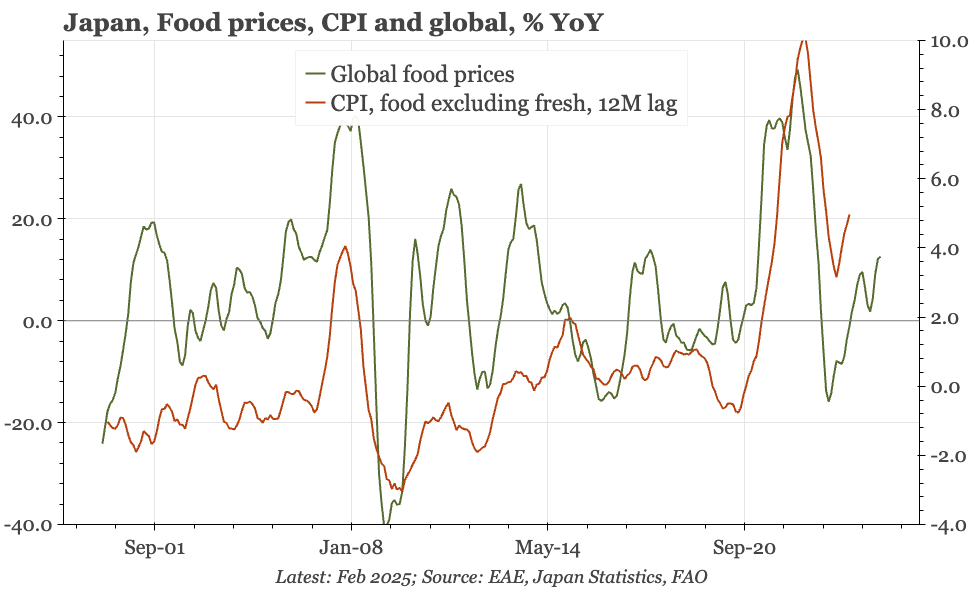

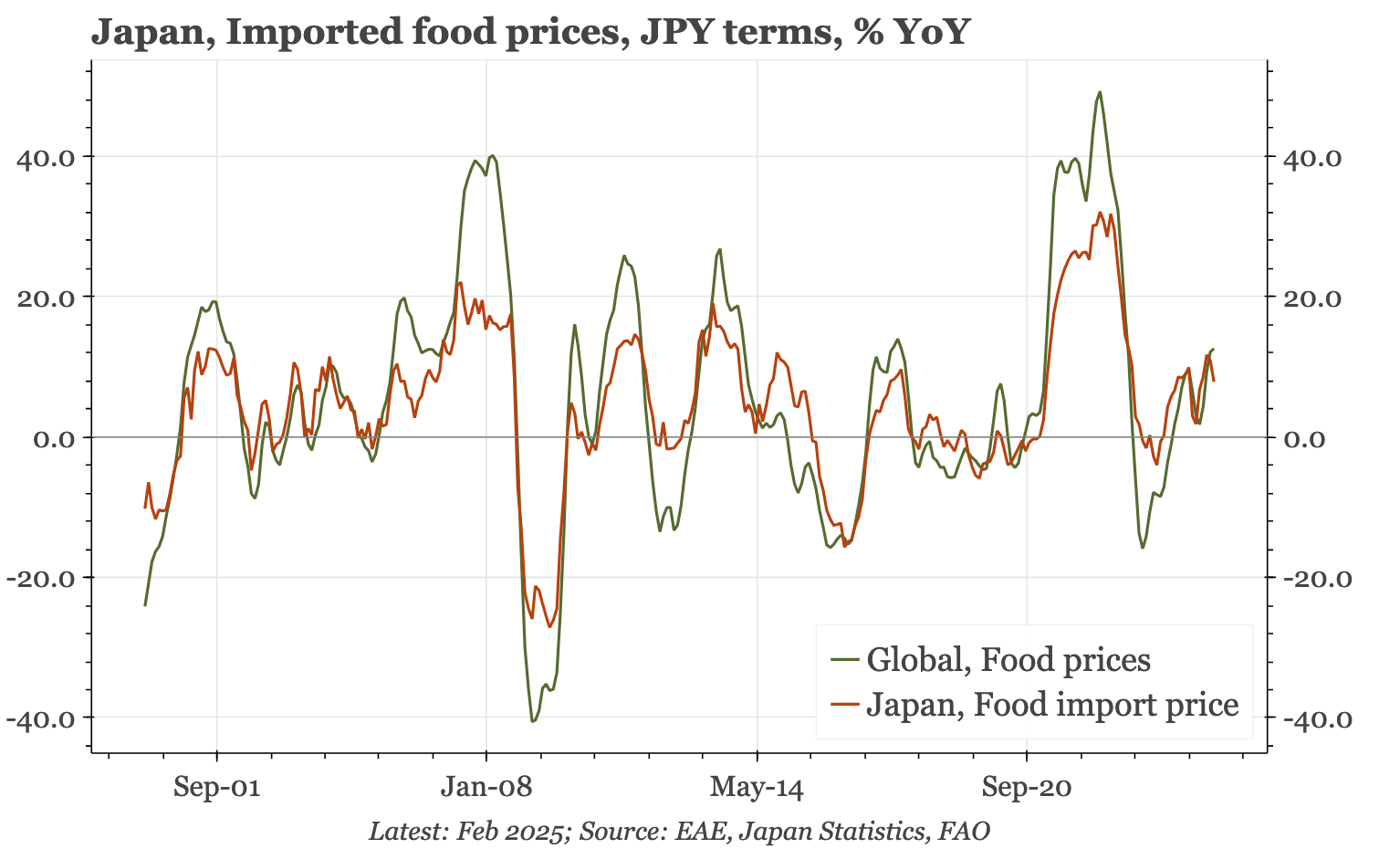

Food prices

It isn't just fruit and vegetable prices that have been rising quickly: inflation in non-fresh food is also high, running at 5%. With Japan far from self-sufficient in food, it might be assumed that this is all because of JPY weakness pushing up import prices. However, the relationship between global and JPY CPI food prices is loose, with domestic prices being determined my many factors other than the exchange rate. That includes the cost of labour. According to Japan's Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, wages have accounted for 30% of the rise in total production costs of different vegetables in recent years. That will reflect the increase in wage costs seen in the standard labour market statistics, which will attract workers away from agriculture. At the same time, it is difficult to raise productivity in agriculture when the proportion of farmers aged over 75 has tripled from 12.8% in 2000 to 36% in 2023, raising the average age of the rural workforce from 62.2 years to 68.7.

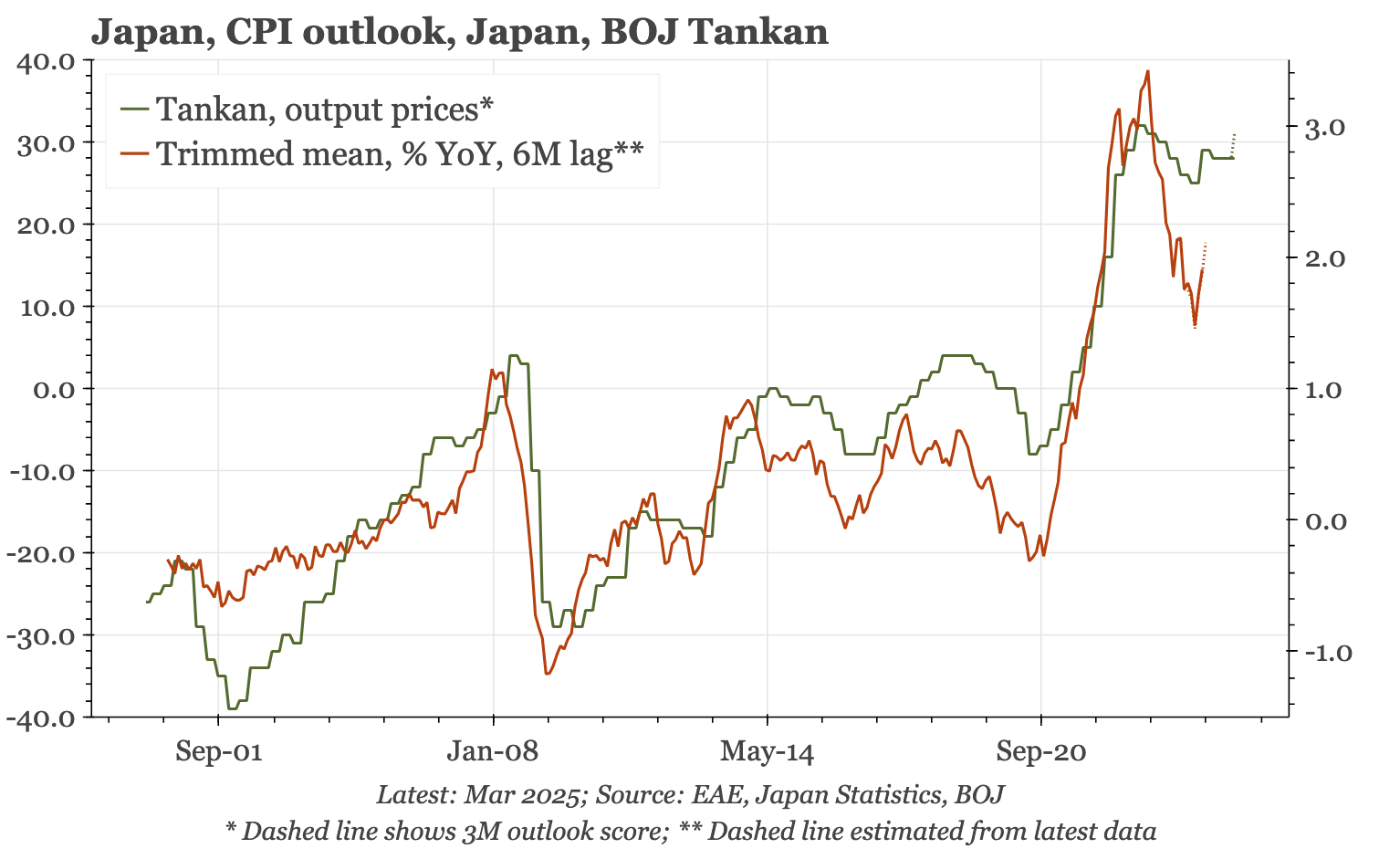

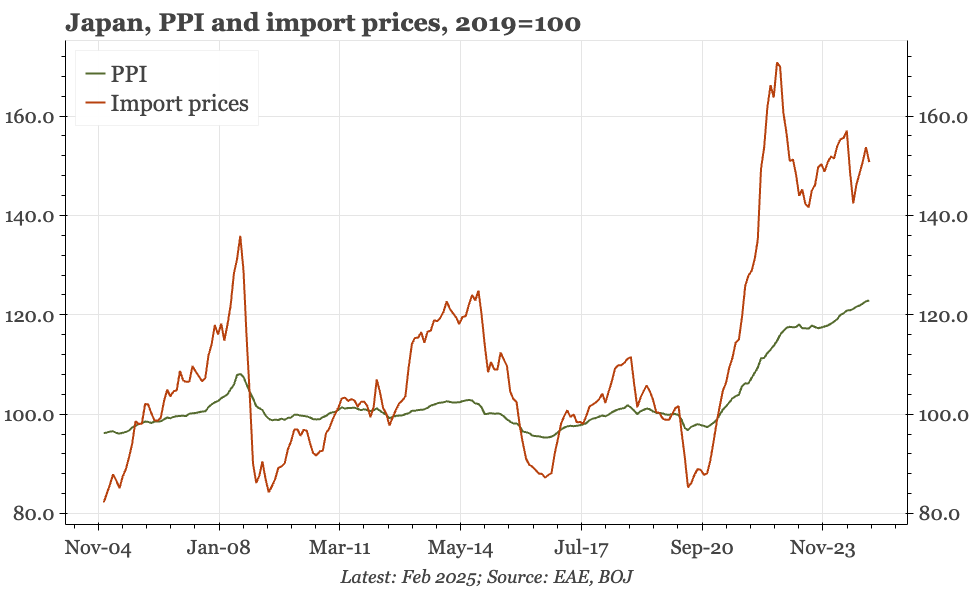

PPI

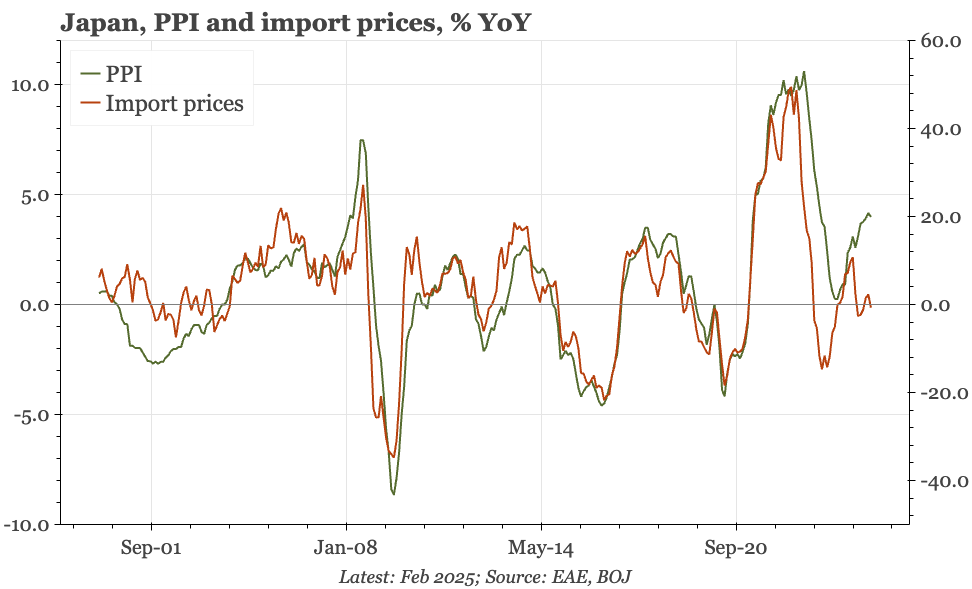

Upstream goods price inflation has accelerated in recent months to reach 4%. That's occurred even though import price inflation has fallen, and means the usual close relationship between PPI and import prices is breaking down. The reason can be understood more by looking at the data in level terms. Import prices tend to be much more volatile than PPI, rising more quickly in upswings, but then experiencing deep corrections, usually because of a combination of global recessions and JPY strength. In this cycle, however, that downwards correction has yet to take place. That leaves import prices much higher than PPI in absolute terms, leasing to pressure for PPI to rise further. There is thus the risk of another round of input price inflation, which will continue to play out unless JPY import prices now do start to fall.

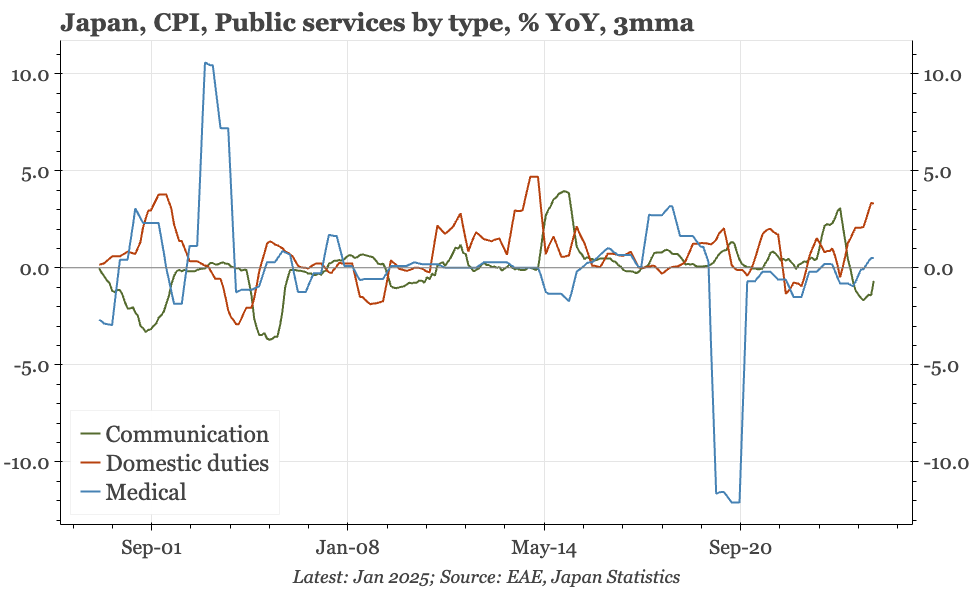

Public services

Essentially, then, upstream prices show pent-up inflationary pressure. That same theme can be seen in downstream prices too, in particular in the costs of public services. While slowly, these were at least rising before 2020. But because of first covid crisis, and then the sharp price rises for other goods and services, the government has held back from increasing public service prices. From a political perspective, that is understandable. But it is unlikely to be sustainable, with the public sector facing the same wage pressures that are driving up private services prices.

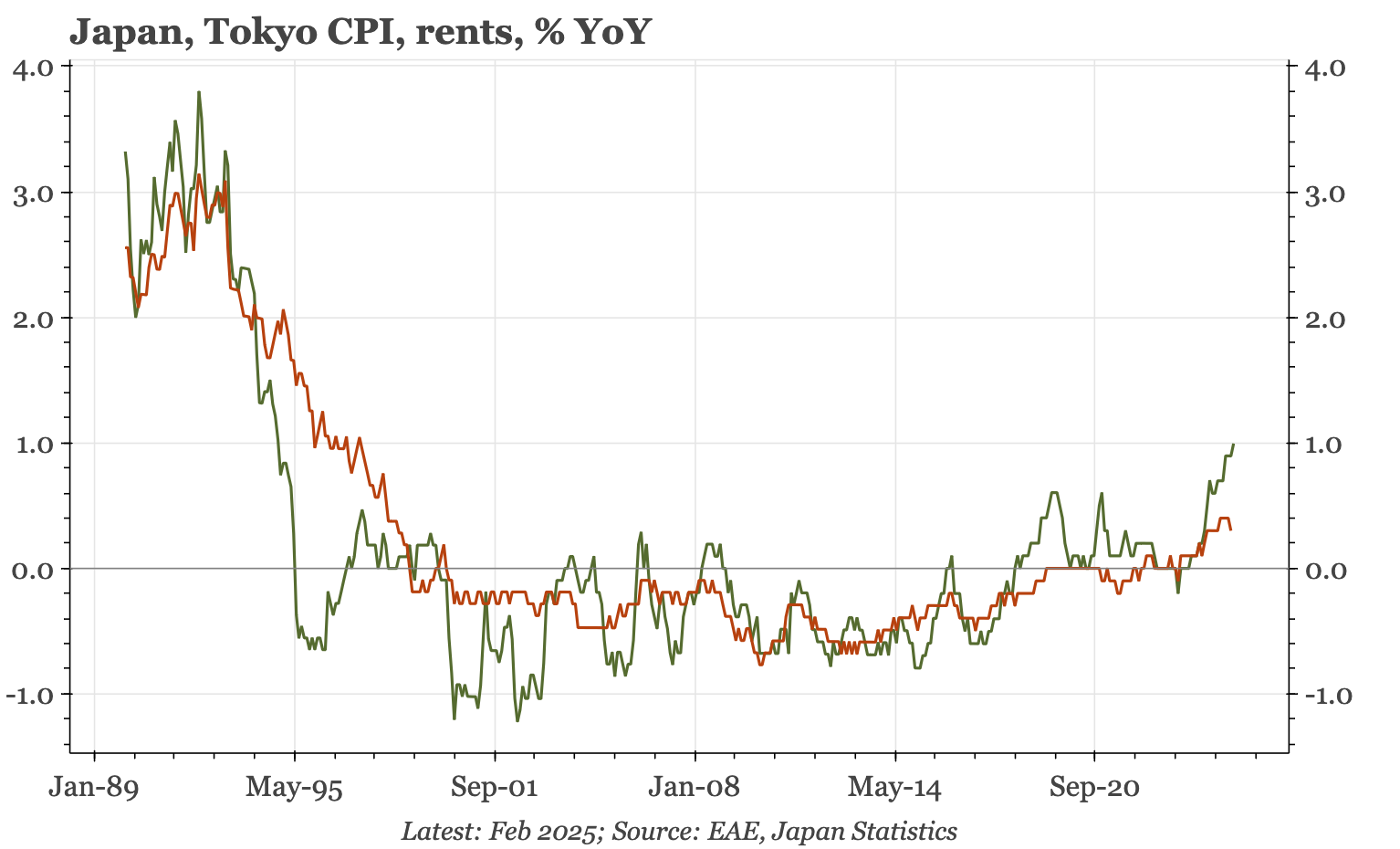

Rents

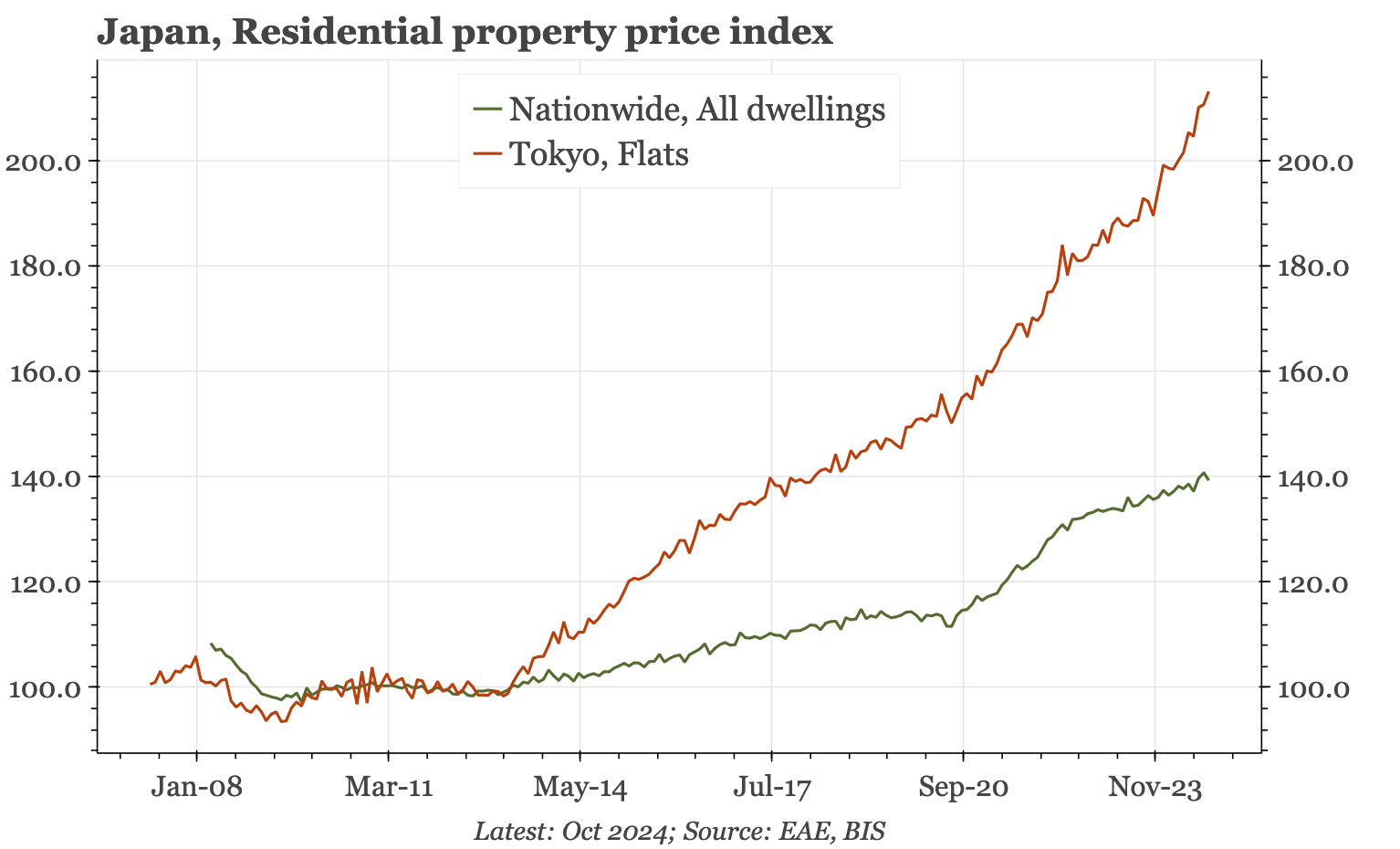

Including actual and imputed, and rents have a 25% weighting in Japan's CPI. The fact that rents haven't moved for years, then, is an important reason why the overall CPI index also hasn't changed. However, the rental market is now showing some signs of life. In Tokyo in February, private rents rose by 1% YoY, the highest since late 1994. Given the rise in property prices, this acceleration likely has some way to turn yet, and rising rents in the capital should start to drag up the national figure too.

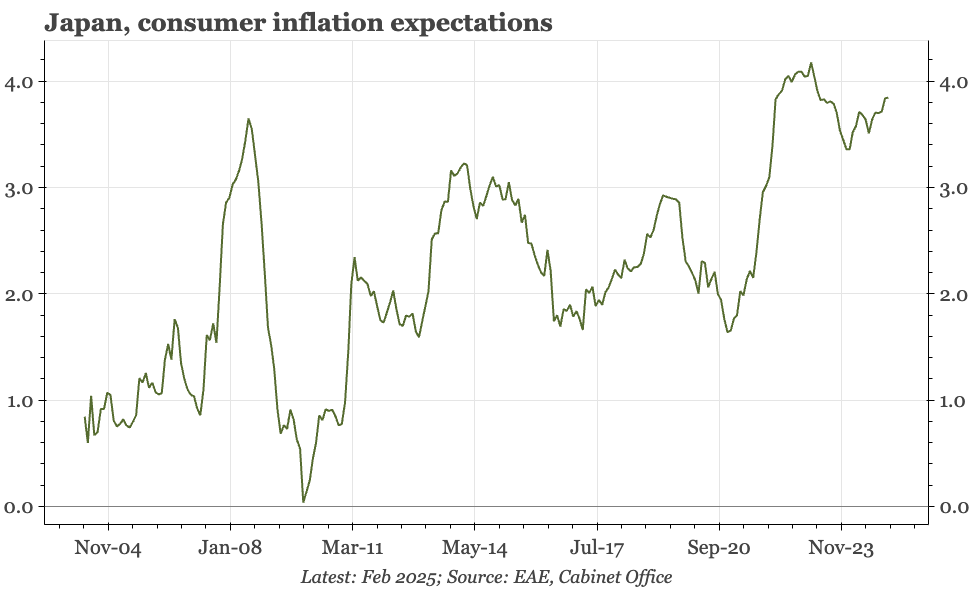

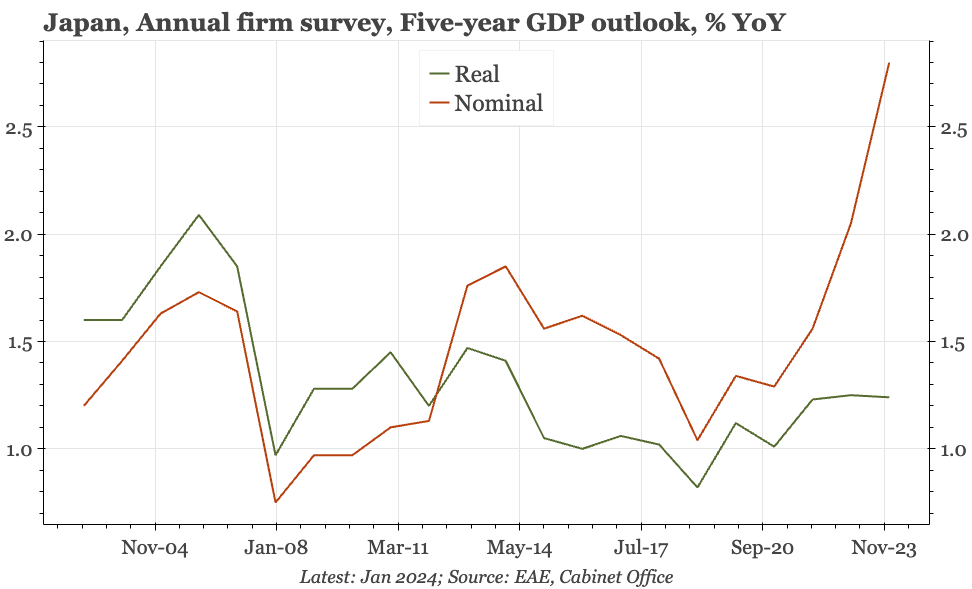

Inflation expectations

Consumer confidence surveys indicate that household inflation expectations have ticked up since Q424, but the more obvious rise has occurred in the corporate sector. That shift was the highlight of the Cabinet Office's annual survey of listed firms, which was released in late February, and showed a further big rise in nominal growth expectations, a shift that is apparent whether firms are asked about the one-, three- or five-year outlook. The real growth outlook, by contrast, isn't changing at all. The gap between nominal and real expectations obviously implies that corporate inflation expectations are rising.