The East Asia Economist

Neither the drop in Korean CPI before 2019, nor the demographic and deflationary experience of Japan, tells us anything definitive about the outlook for price trends in Korea. In fact, it is likely that the country's fiscal position allows Seoul to respond to ageing in a way that isn't deflationary.

The deflationary delusion of Korean demographics

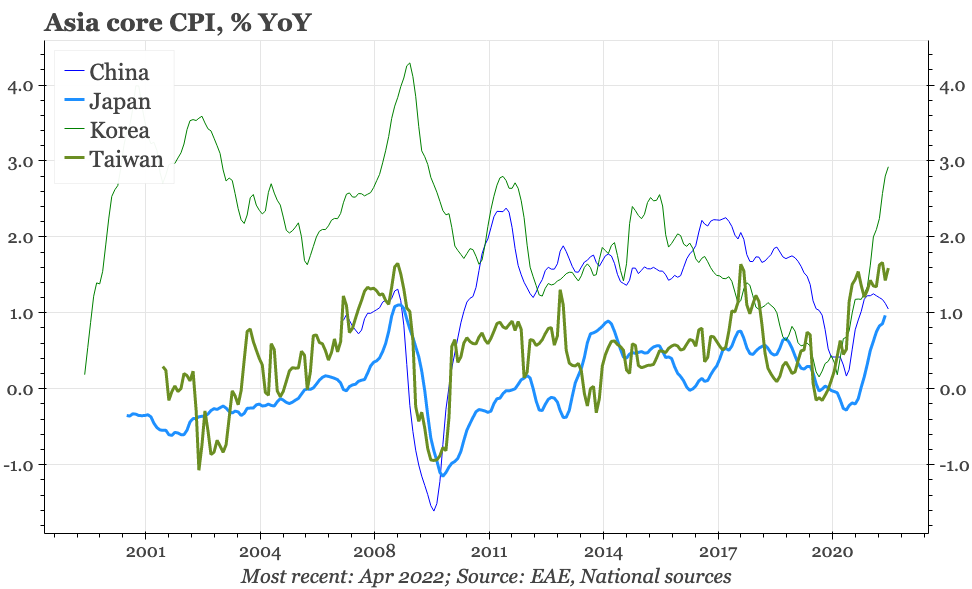

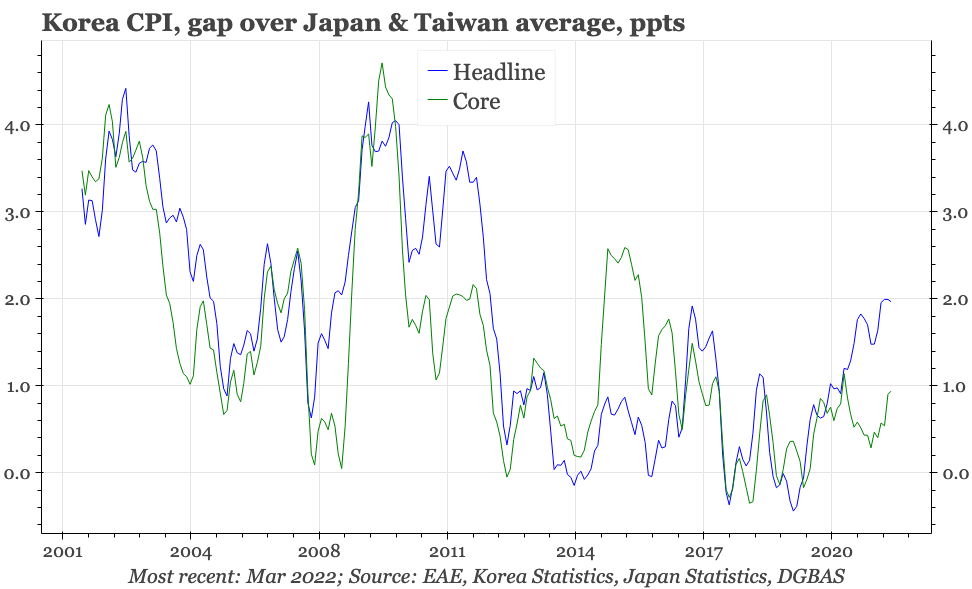

A few years ago, and headline CPI data pointed to Korea shrugging off its history of high inflation and instead slumping into the East Asia club of deflationists (led by Japan, but including Taiwan). That suited a particular line of thinking on how things should work: demographics are important; with a lag of a few years, the rest of East Asia is now ageing more quickly than Japan ever did; and given that Japan has experienced deflation, these other economies should too.

Into 2022 and Korean inflation has surged. For sure, that's part of a global trend, and there's been more rapid price increases in the other rich East Asia economies too. But the rise in inflation in Japan and Taiwan in the last few months has been nowhere near as rapid—the CPI inflation gap between Korea and the deflationists is now as wide as it was ten years ago. All of which raises a couple of questions: are inflation dynamics in Korea really about demographics, and if not, why is Japan deflationary?

Demographics and deflation

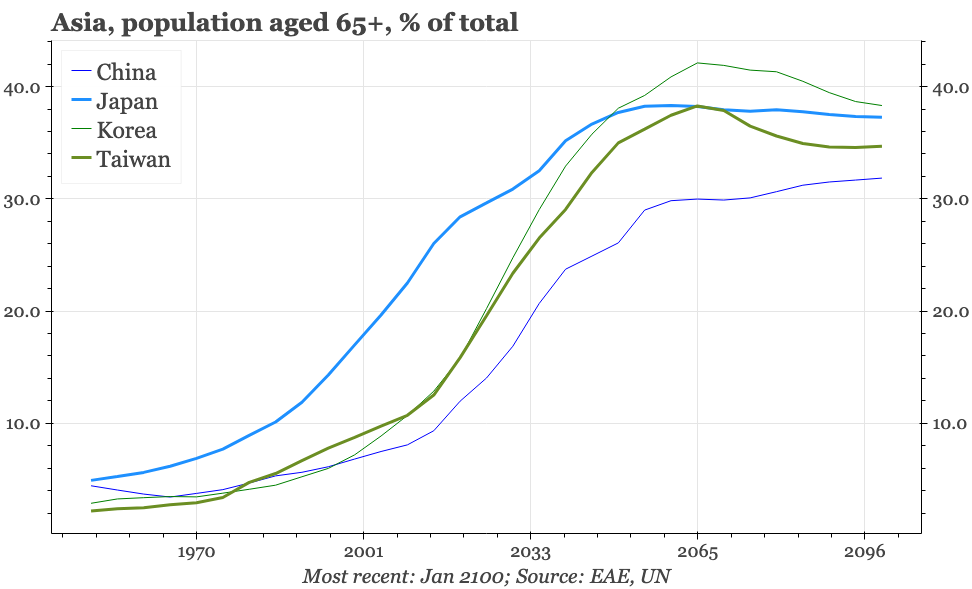

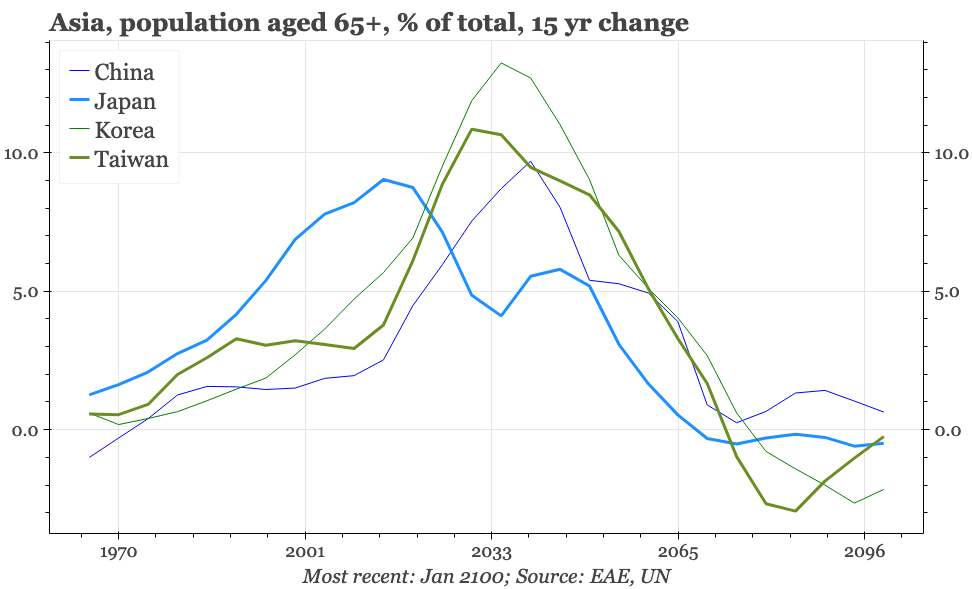

The demographic picture is pretty incontrovertible. As Japan went, so the rest of East Asia is going, but more quickly. The biggest jump in the proportion of the population aged 65 and over in Japan happened in the 15 years to 2015, when the increase was 9ppts. The rate of ageing in Korea lately has already matched that, but it is going to get faster from here: between 2020 and 2035, over 65s are forecast by the UN to rise from under 16% of the population to almost 30%. Differences in the speed of ageing as measured by the over 80s population look similar.

These demographic shifts in Japan happened at the same time as the economy fell into deflation. So, it has been tempting to assume that the sharp fall in inflation in Korea in the years before the Covid-19 pandemic showed again the impact of ageing. Korean headline CPI inflation averaged a bit over 5% in the 1990s, 3% in the 2000s, but under 2% in the 2010s. In late 2019 CPI fell in Korea for the first time on record.

Goods v services prices

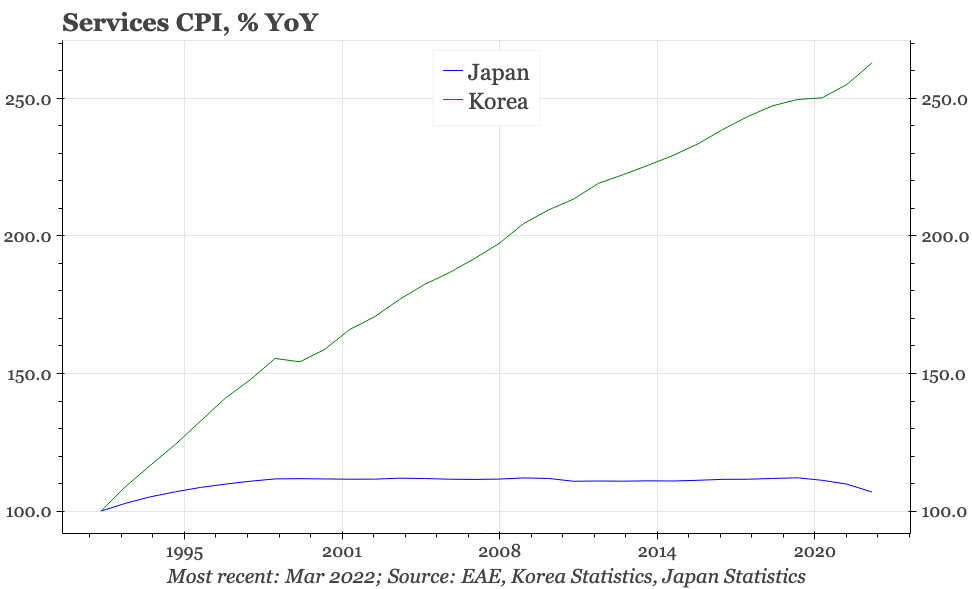

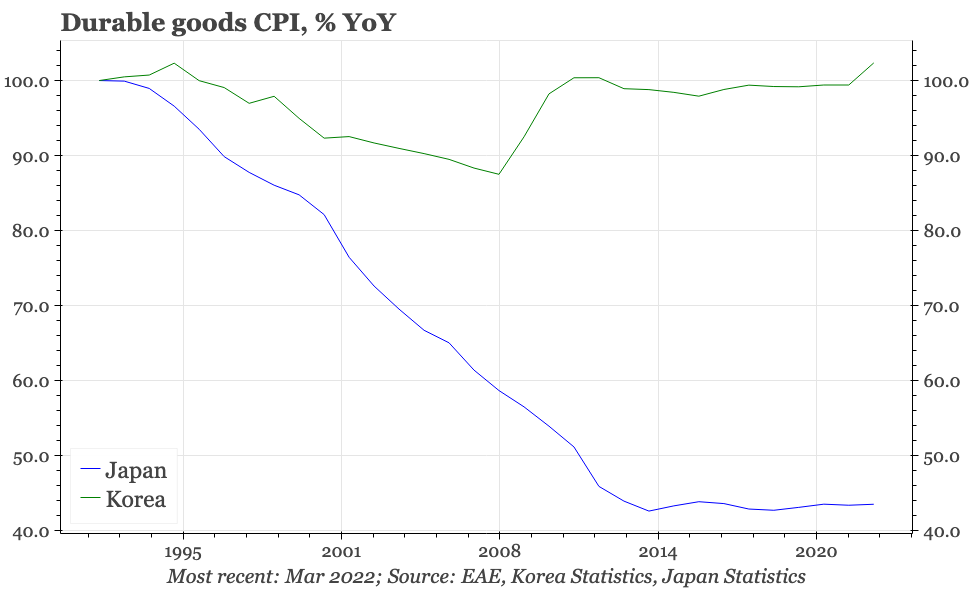

This is a neat, convenient over-arching narrative. Unfortunately, it misses many important details. For one thing, it isn't at all clear that demographics causes deflation, in general, or specifically in Japan. As an illustration, when analysing inflation it can be useful to think of price changes for two different sectors of an economy, on the one hand goods, and on the other services. The usual idea is, as goods are tradeable internationally, so global factors influence their prices. If there is to be a differentiated price trend not linked to events in the rest of the world, it is more likely to show up in services.

There are a lot of possible causative mechanisms for inflation—or deflation. But one common one would be a wage-price spiral. If prices were falling, this spiral would mean companies then have to cut wages. That in turn depresses nominal aggregate demand, a change that pushes prices down yet further. This process would ultimately start to be seen in goods prices, but as they are also influenced by international factors, it is more likely to first appear in CPI for services.

When looking at inflationary trends in East Asia, one difficulty is that the more obvious deflationary trend in prices in Japan has actually been in goods. Certainly, services price inflation has been weak, averaging under +1% YoY in the years between 1990 and 2013. But the real kicker for deflation came from goods prices, which in the same period fell at an average rate of -3.5% YoY. That was quite different to trends seen elsewhere, and suggests specific issues with Japanese manufacturing, specifically the fall from grace of its electronics industry, was an important idiosyncratic driver of the emergence of deflation.

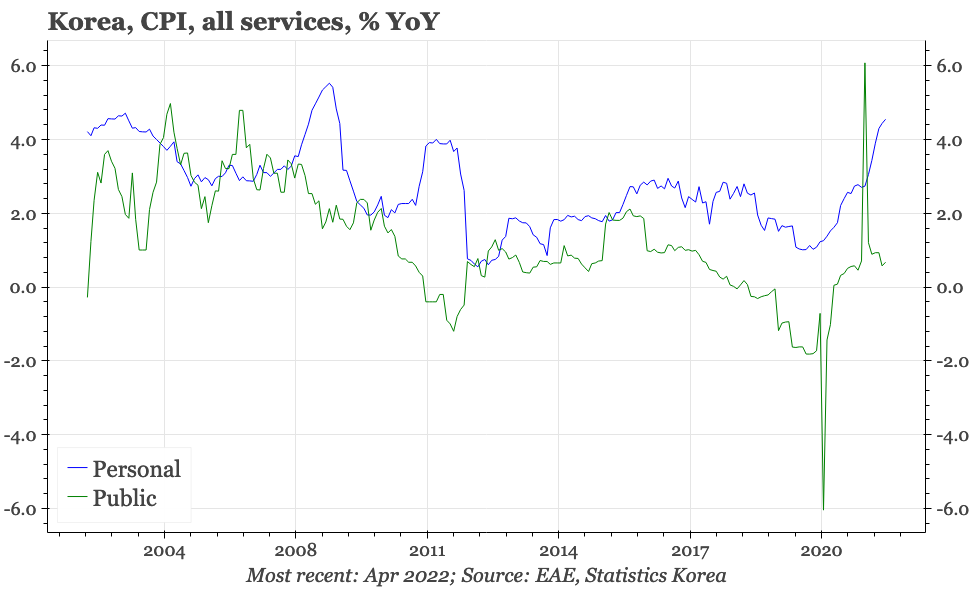

On the surface, the collapse in inflation in Korea into 2019 does look more domestically driven, being led by services prices. But the big driver of that trend was cuts in the costs of public services, as the government gave out bigger subsidies for things like tuition fees. Inflation in public services prices fell from around +1% a year from 2012 until 2017 to -0.9% in 2019. This fall dragged down private service prices too, but not to the same extent. Even at the lowest point in 2020, private sector price inflation in Korea was still running at +1% YoY.

Such a big change in public services price inflation was always quite likely to be temporary. Most governments can't afford to expand subsidies forever; even if they could, once all public services were free, the impact on inflation would disappear. And so it proved in Korea. There were a few more giveaways as the government sought to provide fiscal help during the Covid-19 pandemic, culminating in October 2020 when public services CPI fell by -6% YoY. But that was the trough. Since then, the process has reversed, and public services price inflation is now running at +0.7% YoY, roughly where it was between 2012 and 2017. As that happened, so private services inflation has rebounded, to reach +4.5% last month, the highest since early 2009.

Wages and supply-side dynamics

Obviously, the last couple of years have been particularly volatile for economies everywhere, including Korea. There was the huge negative shock caused by the initial outbreak of Covid-19, and then the big positive boost from all the policy support provided as the pandemic spread. Given this, it is tempting to think this rise in services inflation will be short-lived. It could be; again, there are quite a few different causal mechanisms for inflation. But at least regarding one of those, the wage-price spiral, the backdrop in Korea looks more inflationary than deflationary. While high-quality and timely wage data aren't available, the different indicators we do have all point to wage growth is running at around 4-5%.

That's quite a contrast with Japan, where at least before Abenomics, wage growth was anaemic. To be frank, that doesn't look like a negative wage-price spiral either; moreover, there are real signs now of wage growth starting to pick-up. Still, while in the years before 2013 wage growth didn't spiral down below zero, it was low enough to be consistent with non-existent price inflation.

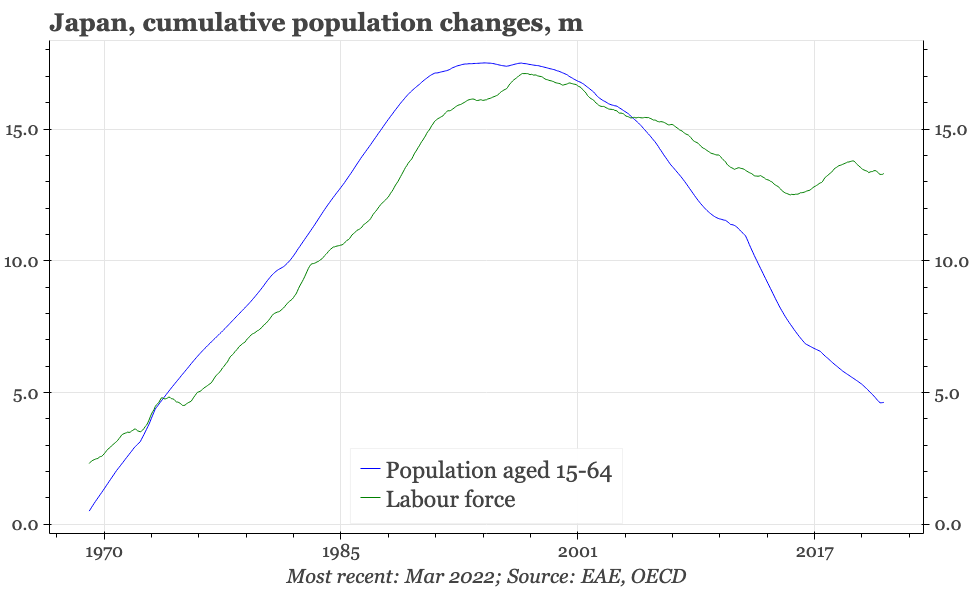

Whether the low rate of wage growth is a function of Japan's demographics is another matter. One of the consequences of an ageing population should be that the working population shrinks, so from a supply perspective at least, that should mean some upwards pressure on wages. The working age population in Japan has indeed dropped by around 13m between 1995 and 2022, but in the same period the labour force has shrunk by a more modest 4m people, and since 2016 has actually increased. That's been driven by three developments: a rise in the female participation rate; an increase in the proportion of people over the age of 65 who are still working; and, at least before Covid-19, a rise in the number of migrant workers.

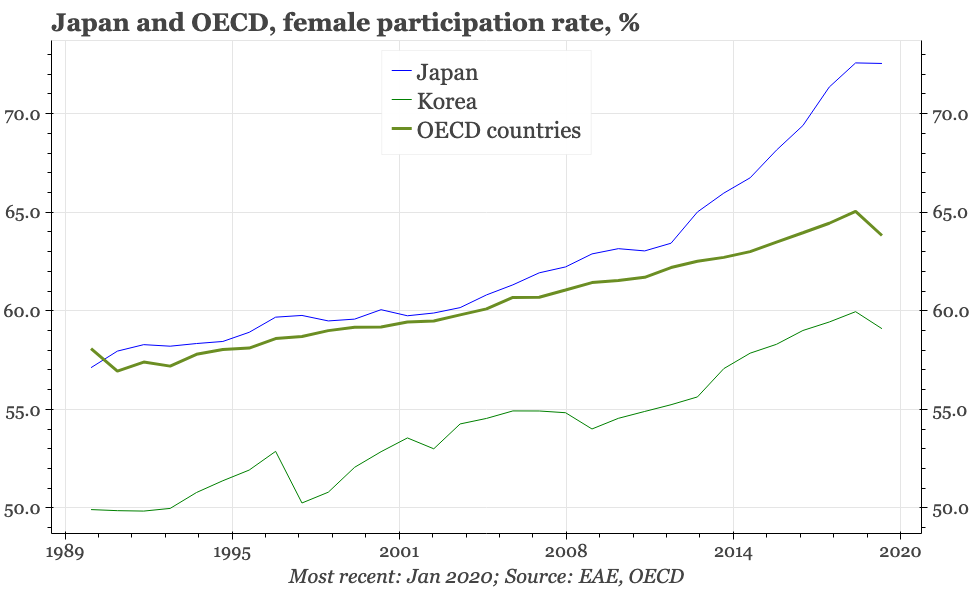

This strongly suggests that the relationship between the actual number of people of “working age” and the number of people actually working isn't fixed, being influenced by policy and other external factors. This point is particularly relevant to Korea, where the elderly participation rate is quite high, but the percentage of women who are working is even lower than it was in Japan in the early 2000s. Of course, there's powerful cultural and institutional reasons for this situation. But cultural factors were at one time considered to be over-powering in Japan, and while there are still many constraints to women there achieving real equality in the workplace, the progress made in the last few years has been substantial.

Pensions and demand-side dynamics

If supply side dynamics don't offer a very convincing explanation for wage-price developments, then it must be that changes in demand have been the more important dynamic. In looking at demand and the impact on inflation in Japan, in turns out that demographics are indeed significant. But the role played by demographics in demand isn't the one that is most commonly discussed, and that has consequences for the impact that the ageing of the population might have in the coming years in Korea.

In discussing demand, it is worth remembering that it isn't necessarily true that an ageing population depresses aggregate spending in an economy. The classic life-cycle model of consumption would, in fact, suggest the opposite. The idea in this common economic framework is that households budget for their whole life, meaning they spend less than they earn when working, allowing them to build-up savings so they can spend more than their pensions once retired.

This kind of pattern can often be seen in actual savings ratios, which tend to be high for workers, and low or negative for retirees. In Japan, that is true today, but wasn't so obvious in the early 1990s after the bursting of the bubble. Then, savings ratios for older workers and early retirees held up, as they sought to compensate for the damage done to the value of their savings by the sudden fall in asset prices. By upsetting the lifecycle model, that would have potentially depressed aggregate demand, putting downwards pressure on prices.

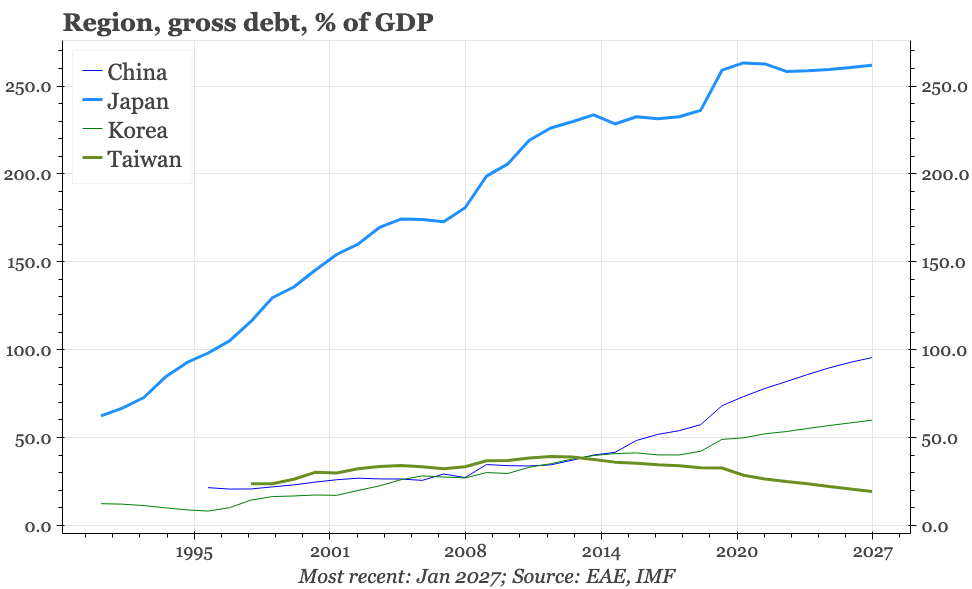

That was a significant development, but again, one that now seems to have normalised (admittedly that's truer from an income perspective, but less clear when looking at wealth). That said, the impact of the bursting of the bubble, and the interaction of that with demographics, has lived on, and is indeed having a significant impact on Japan's macro situation today. Needless to say, in the years since the bubble burst, the Japanese government has run up a significant amount of debt. At the same time, the continued ageing of the population inevitably brings a rise in demand for yet more public spending on pensions, medical care and other social services.

Fiscal dynamics and ageing

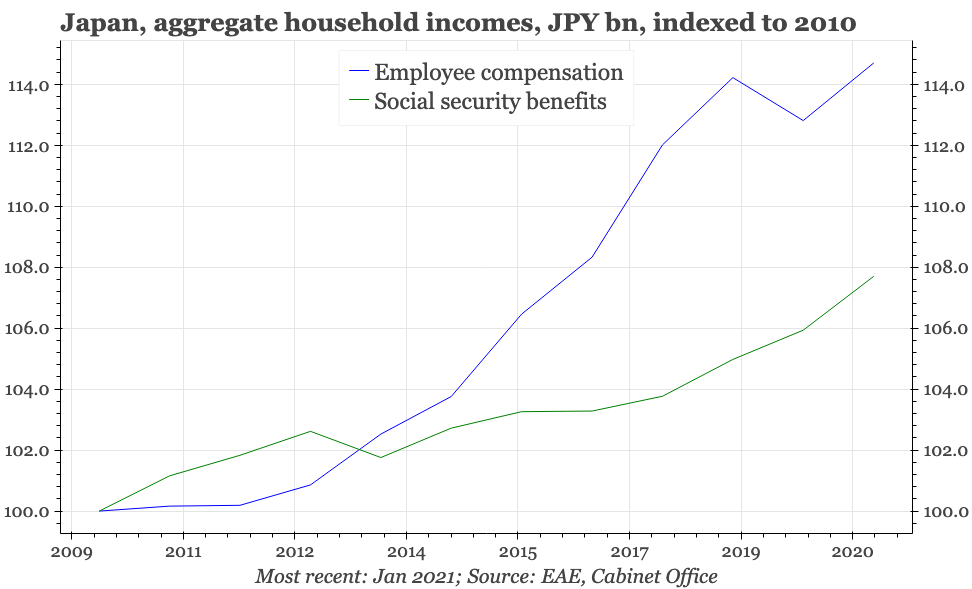

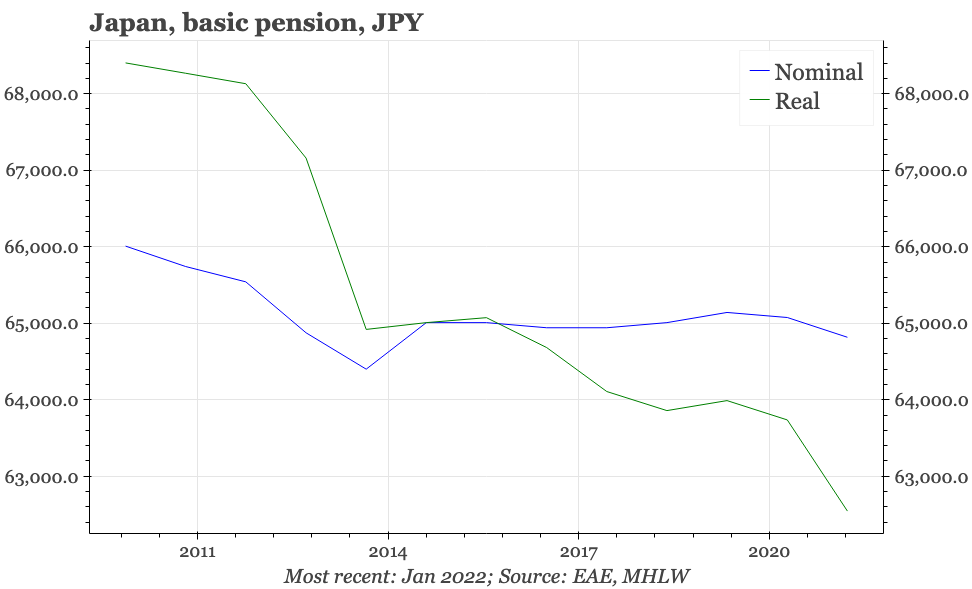

Faced with this situation, the Japanese government has made changes to try to constrain the cost of these demands. One that is particularly relevant today is the 2004 legislative reforms that allowed public pensions to be negatively indexed with inflation. As a result, despite the continued ageing of the population, total pension payments from the government fell from 14.6% of GDP in 2009 to 13.6% in 2017. That in turn has helped constrain the growth in total social security payments to less than 8% in the last ten years – a rate of growth that likely would have been even lower had it not been for the fiscal support offered during the Covid-19 crisis.

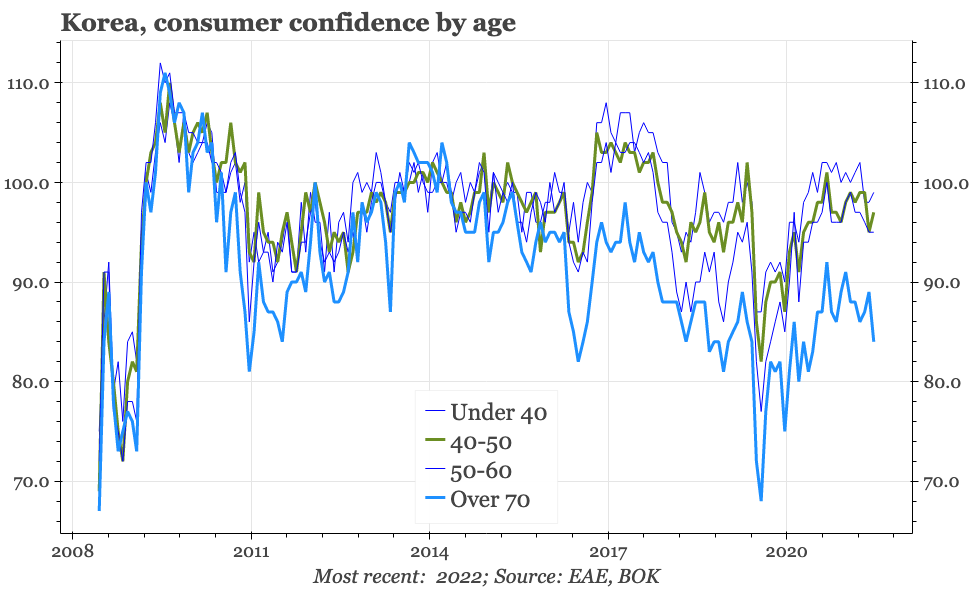

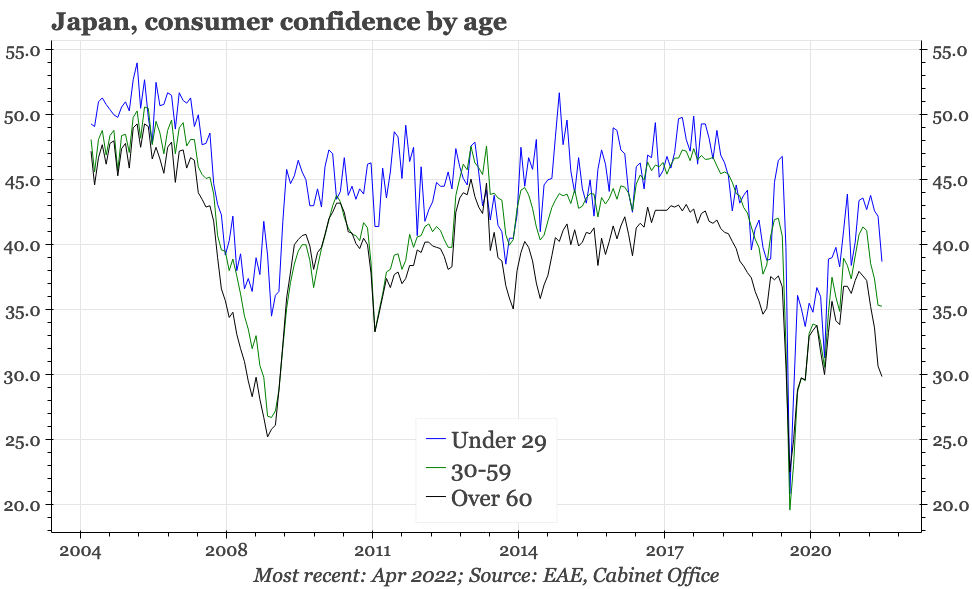

In terms of public policy, this fiscal constraint is an important, and perhaps even admirable, achievement. Unfortunately, it isn't yet clear what economic benefits it has generated for Japan. Public debt has continued to rise anyway, driven up by the various shocks that have hit Japan, with the financial crisis of 2008 and the Great Tohuku Earthquake in 2011 preceding Covid-19. At the same time, the fiscal changes have clearly affected the purchasing power and sentiment of the 30% – and rising – proportion of the population who are dependent on pensions for their incomes. The standard old-age basic pension today pays JPY64,817/month, compared with JPY66,008/month in 2010, which in real terms implies a fall of more than 8%. It seems likely that this explains the weak consumer sentiment of elderly people, which has clearly lagged the rest of the population since 2014.

One consequence is that wage growth for the 60% of Japan's population still working has to be even higher than the official average of around 1% during the last few years to lift overall aggregate demand. Japan's economy really needs to be run "hot", which implies that even with the unemployment rate hovering at a 30-year low, the labour market still isn't tight enough.

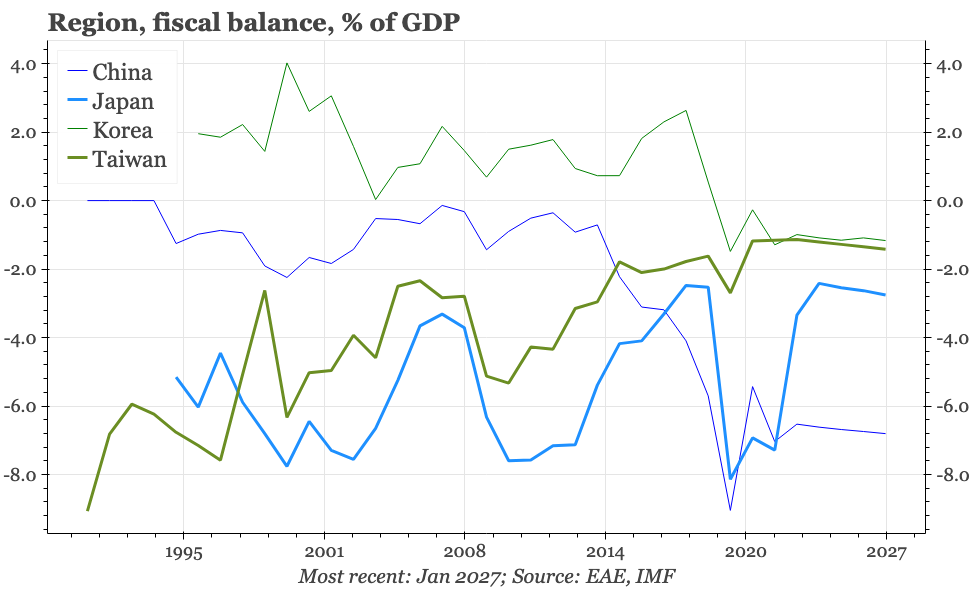

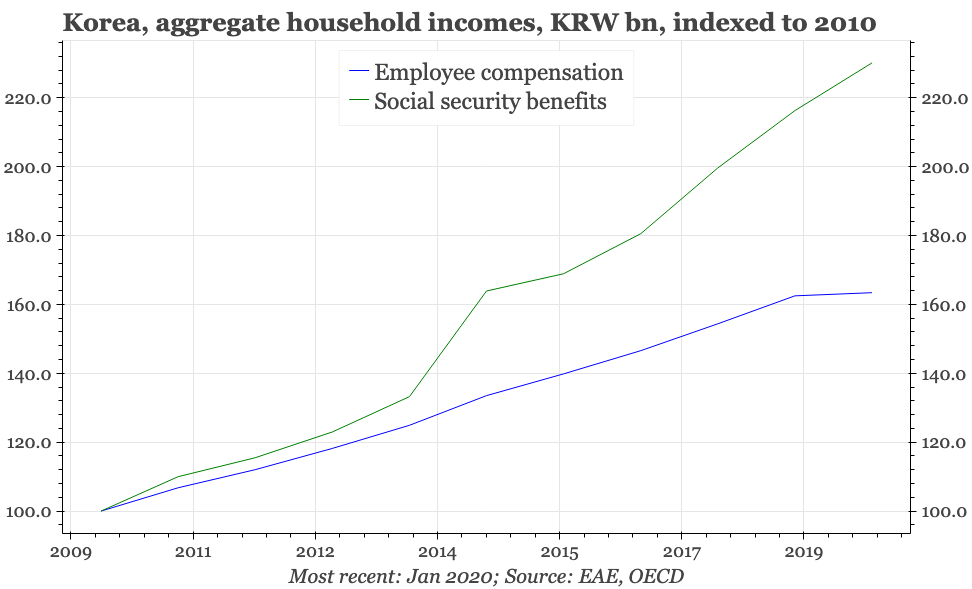

Korea doesn't face nearly the same fiscal constraints. Public debt in the country is still a little under 50% of GDP, obviously much less than Japan's 260%, but also much healthier than the 100% levels now common across the other OECD countries. The debt level has been rising in recent years as the fiscal deficit has increased, partly to fund social security outlays. Aggregate welfare payments to households have more than doubled since 2009, which isn't just a far bigger increase than in Japan, and also a faster rise than the aggregate increase in Korean employee earnings.

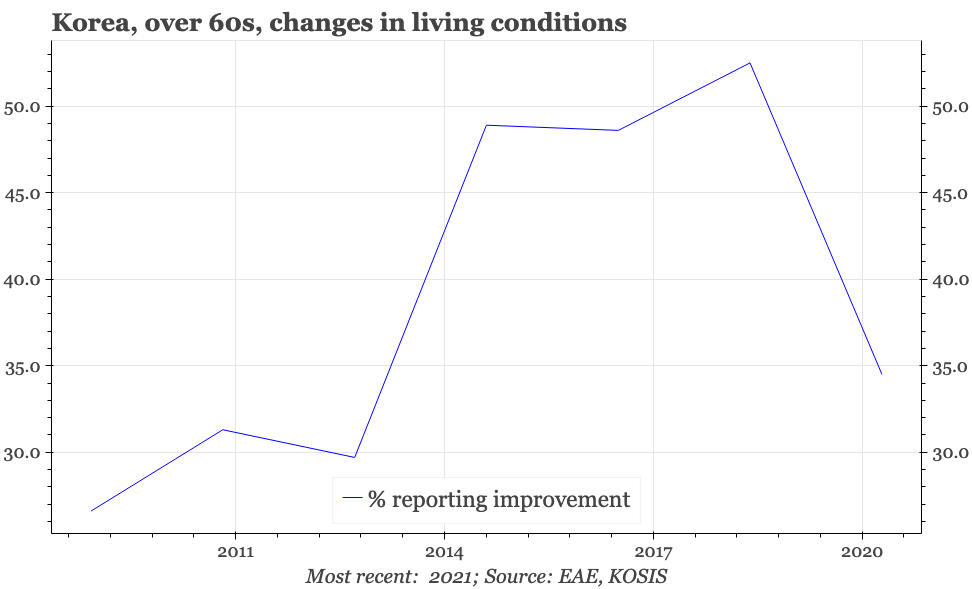

The backdrop to this change in Korea was an inadequate social security system, a deficiency that is certainly far from being fully resolved. Korea has suffered from the highest incidence of elderly poverty rate in the OECD; net pension replacement rates are low compared with other advanced economies; and, as in Japan, consumer confidence of the over 70s lags that of the rest of the population. But there are signs that the changes in welfare policy in Korea have started to make a difference. According to Statistics Korea, the proportion of over 60s reporting an improvement in both living conditions and in the social security system was rising fairly steadily pre-covid. For older households, the proportion of income coming from government transfer payments has risen from 10% in 2000 to a bit under 40% in 2016.

None of this is to argue that there is no risk of deflation in Korea, or that ageing isn't an important issue for the economy. The point is that neither Korea's drop in inflation before 2019, nor the demographic and deflationary experience of Japan, tells us anything definitive about the outlook for price trends in Korea. Instead, these points of comparison say more about the impact of policy on inflation. If it wasn't for temporary public sector subsidies, Korean inflation wouldn't have looked particularly low before 2019. As for demographics, there's a long way to go to perfect Korea's pension and welfare system, but Korea's fiscal position should give the authorities in Seoul considerable room to respond to ageing in a way that isn't deflationary for demand.