Korea – cycle worsening, rates to fall

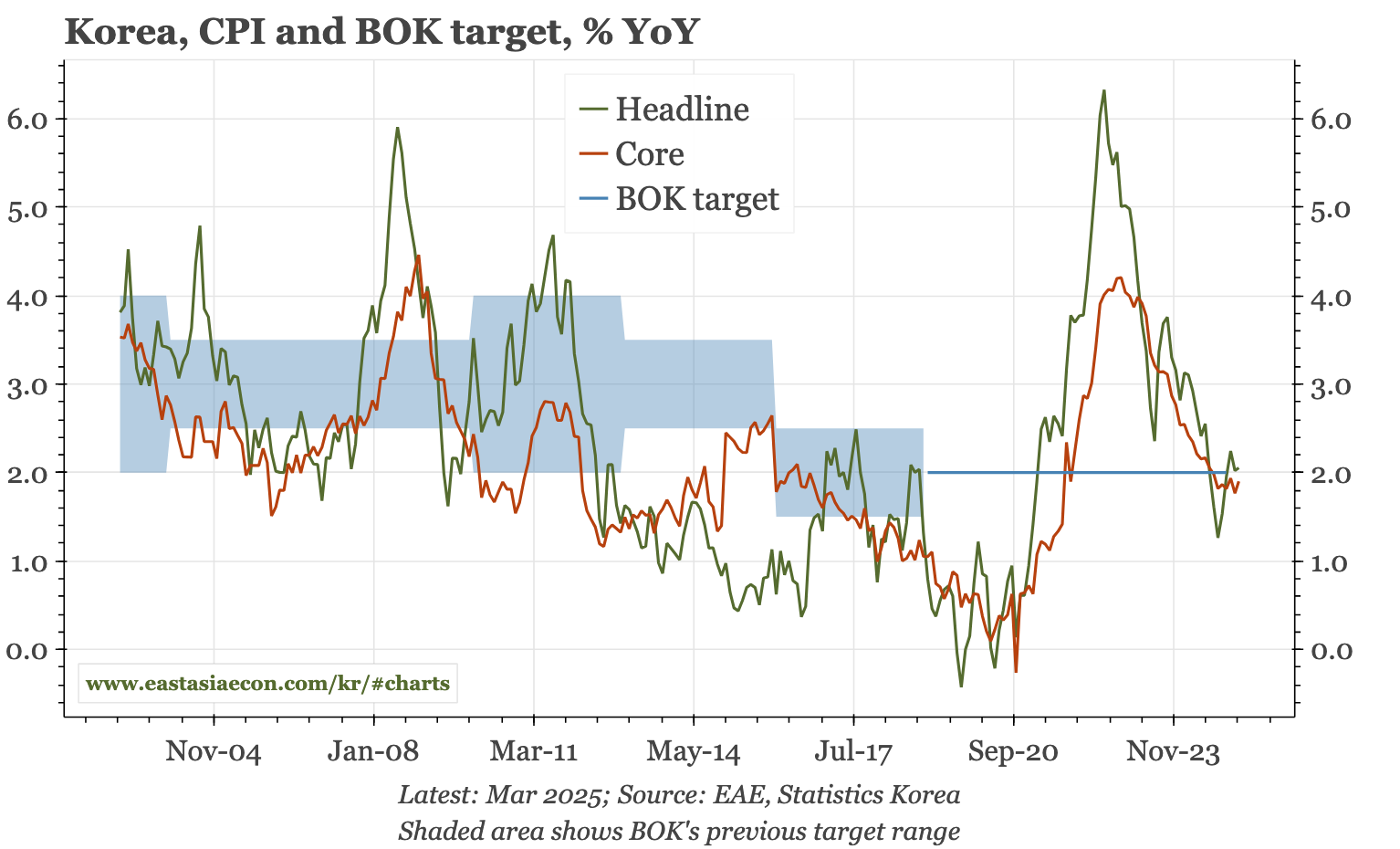

The economic environment for Korea is about as bad as it can get. Despite the short-term rebound in house prices, that suggests more rate cuts, starting at this week's meeting, that will ultimately take the policy rate below neutral. The one caveat I have is the stickiness of services inflation.

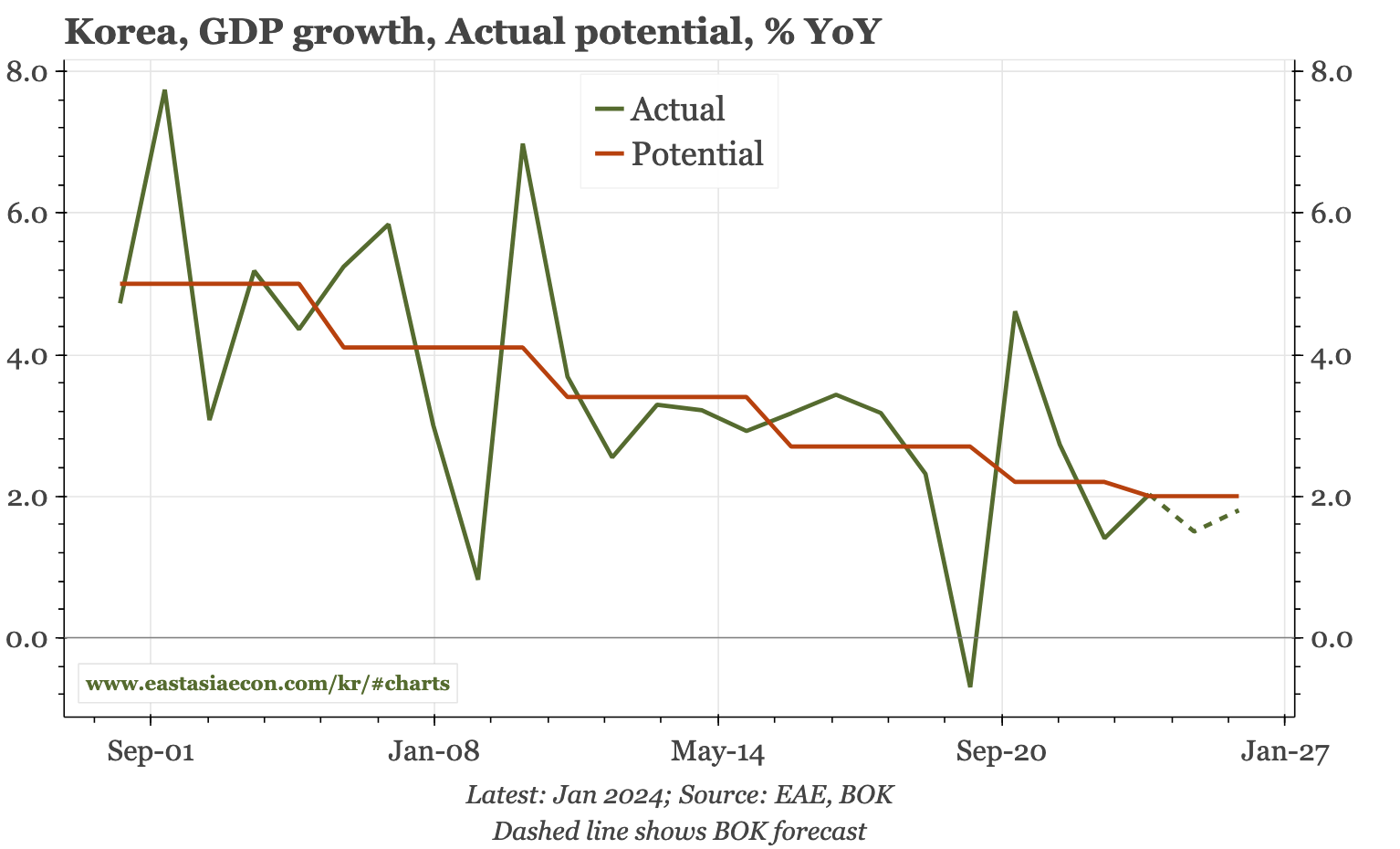

Rates will fall further in Korea, and I'd expect in this cycle they will ultimately be cut below neutral. Even before the true extent of the tariff chaos was known, the BOK was forecasting growth in the next two years would be below the 2% that it believes to be the potential rate. Now, actual growth is highly likely to be even weaker still.

Outside a miraculous clearing of the tariff troubles, the one area of upside risk is fiscal policy, although not just yet. Even before tariffs went up and Korea suffered damaging wildfires, BOK governor Rhee had been calling for a supplementary budget of KRW15-20tn, but in the end, the politicians agreed on just KRW 12tn.

Fiscal policy should be loosened more determinedly after the presidential election in early June, and with the poll easing domestic political uncertainty, it could also lead to a modest improvement in business and consumer sentiment. But that is still some time away, and a change in president won't change the awful external economic environment that Korea is now facing.

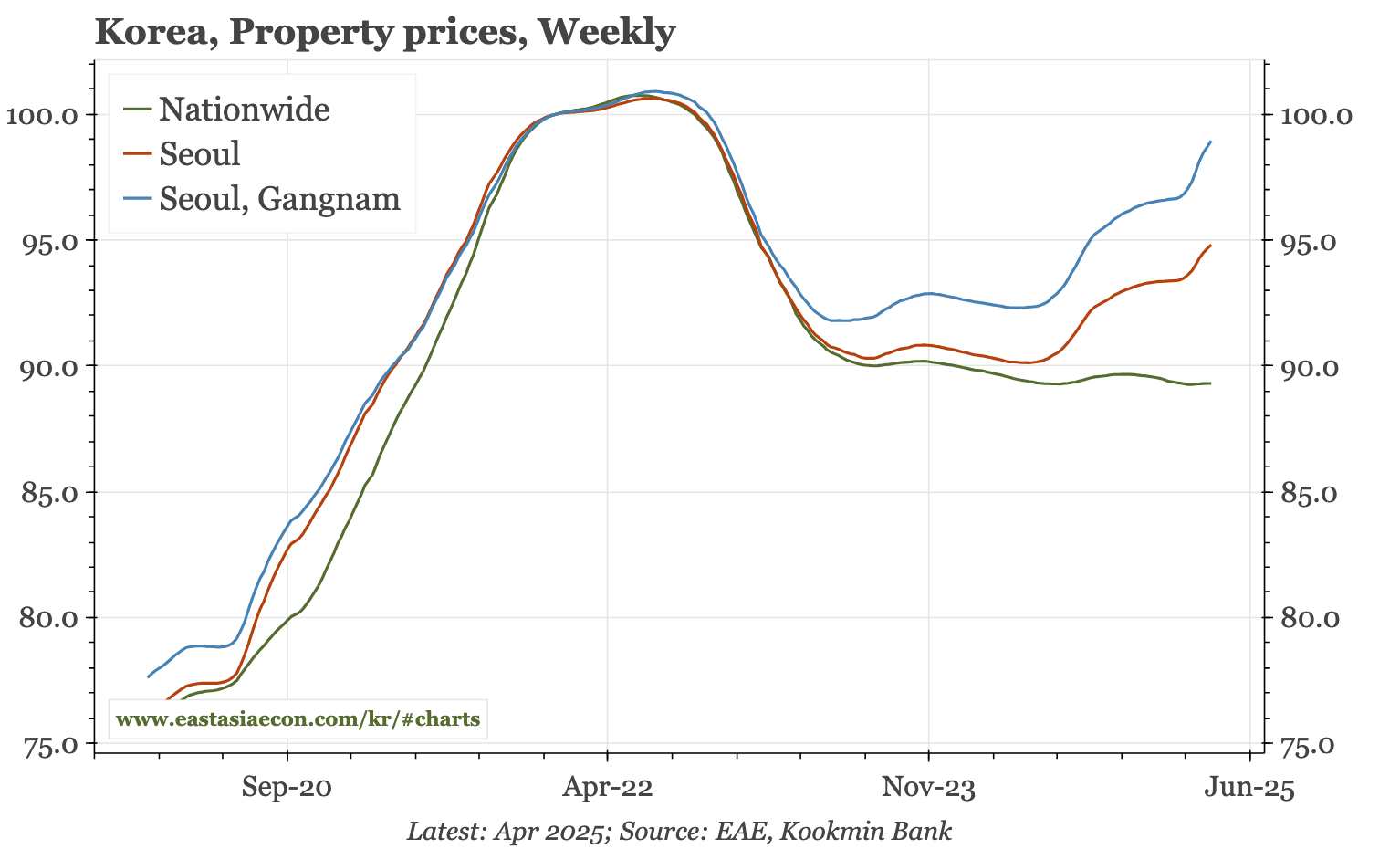

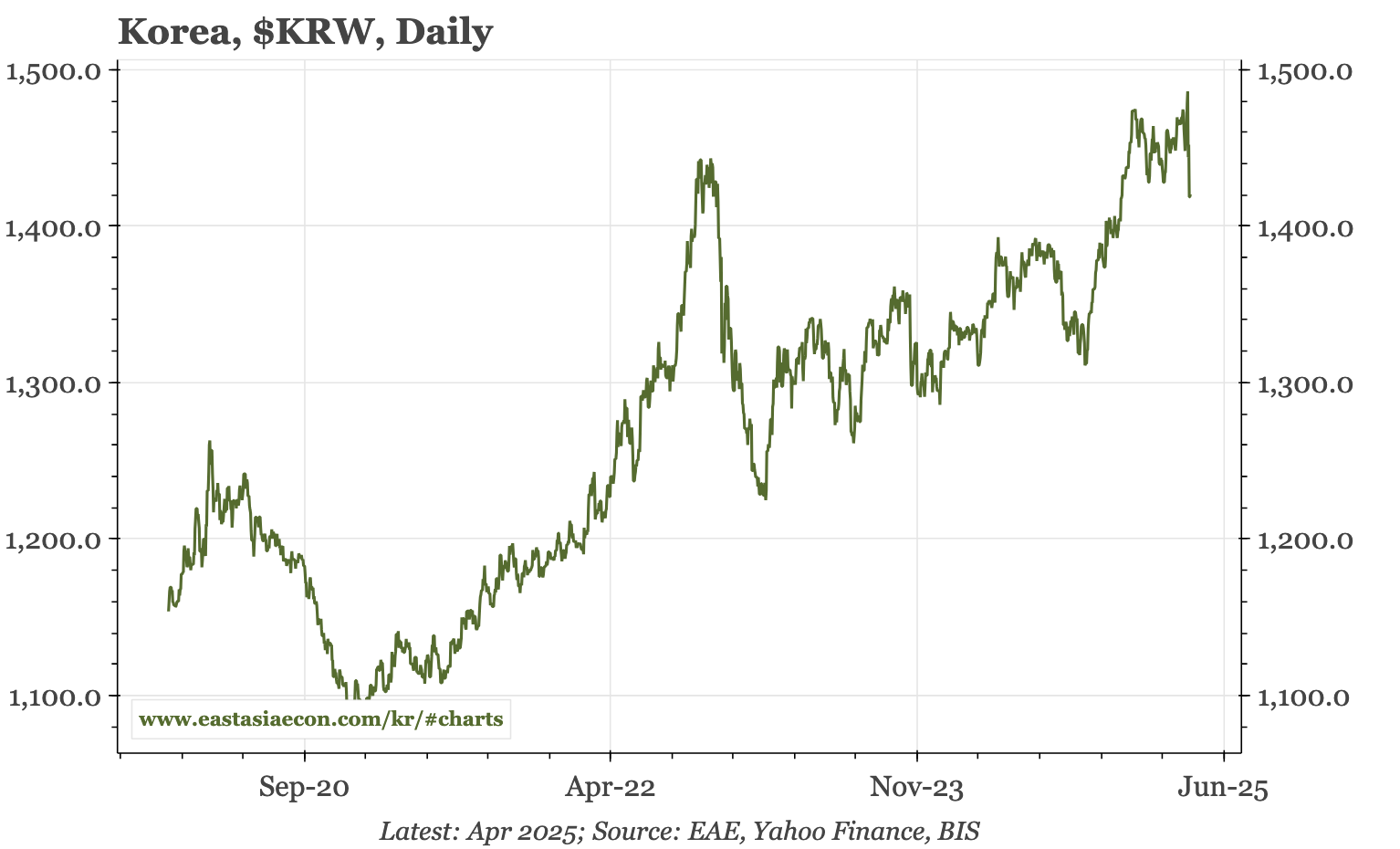

That brings up to this week's meeting. With the KRW strengthening and the BOK still not finding a reason to worry about CPI, the one immediate constraint on the bank acting to boost the cycle is household debt. Never ignored by the BOK, the rebound in house prices in Seoul this year will have again raised this issue up towards the top of the bank's list of concerns.

That is a real issue. The problem for the members of the MPC is that their next meeting is at the end of May, just before the election. Probably, they could cut then, but the timing isn't ideal, meaning if they don't cut this week, they might not be able to until July. So I'd expect a cut this week, and rates to fall yet further in the coming months.

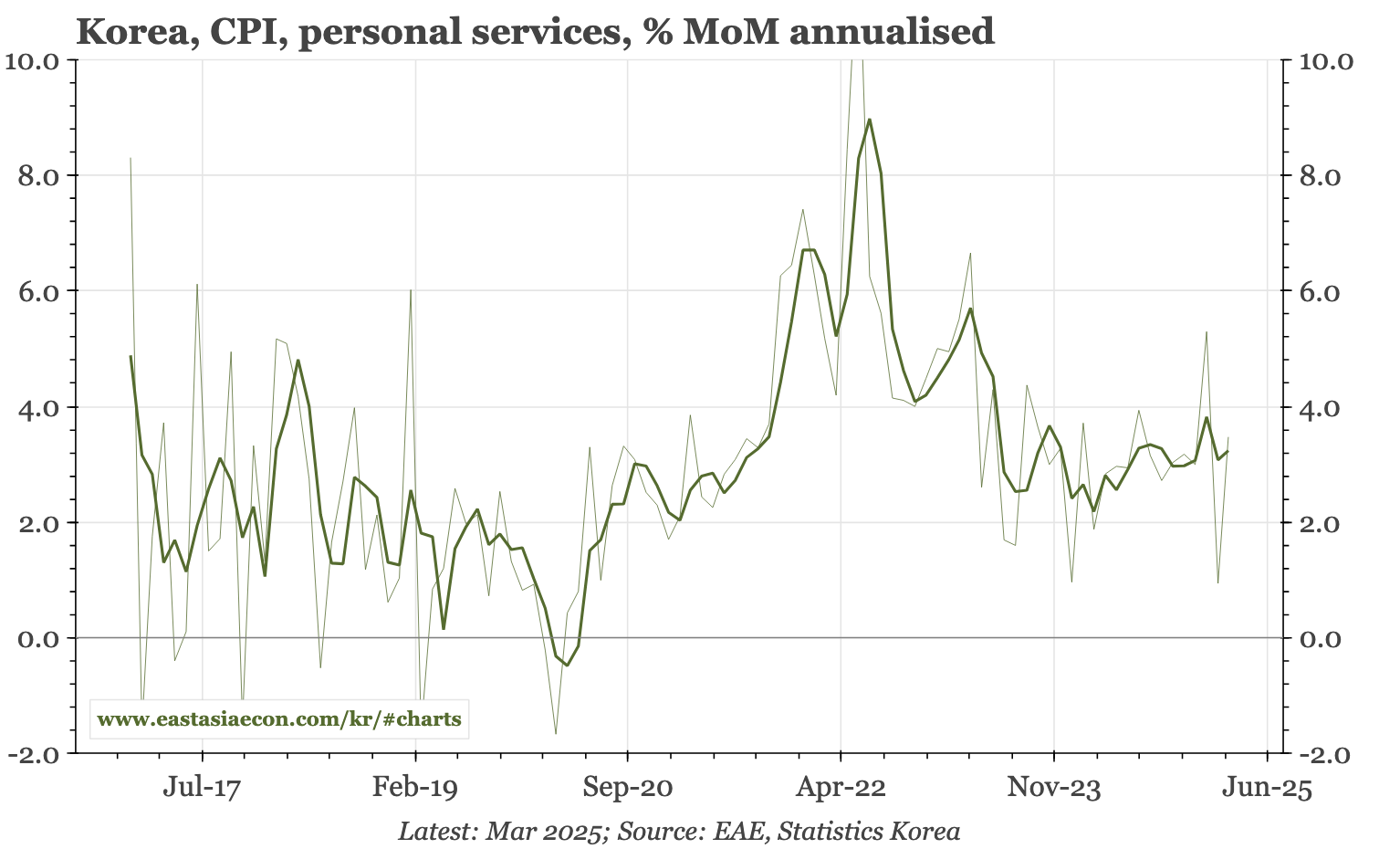

That's my base. The one remaining uncertainty I have is the stickiness of services inflation in Korea. That seems at odds with the BOK's view that CPI isn't a risk, with the output gap already negative, and likely to become more so. I need to do some more work on this.

In recent research, the BOK argued Korean potential growth has now slowed to around 2%, slightly lower than 2.1% in the last estimate of 2021, and quite far from the mid-3% range of the 2010s. The slowdown is because of shrinking contributions from all the main components: total factor productivity, labour and capital.

According to the bank's most recent formal forecasts released in February, actual GDP is expected to grow by 1.5% in 2025 and 1.8% in 2026. Overall, the implication is that the BOK anticipates a negative output gap and so downwards pressure on inflation.

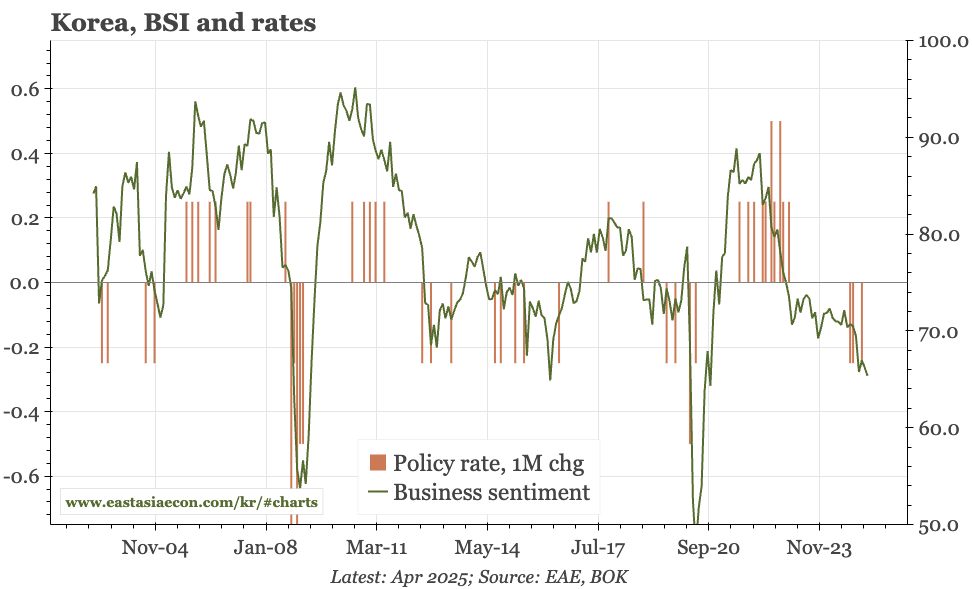

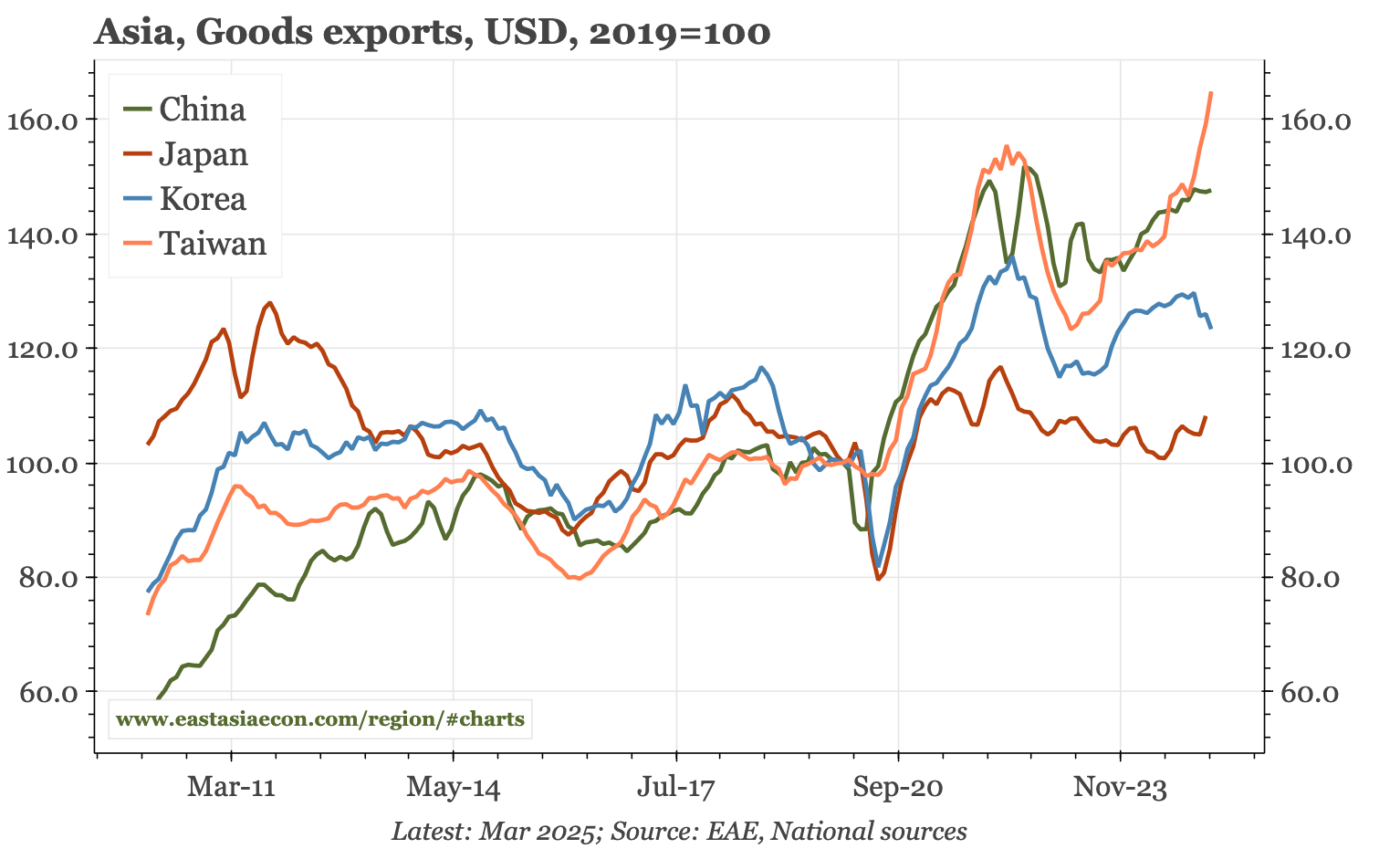

In terms of activity, nothing has happened since February to challenge that view. Business confidence remains extremely depressed, exports have been sluggish – in absolute terms, and even more relative to Taiwan – and some signs of slack have begun to appear in the labour market.

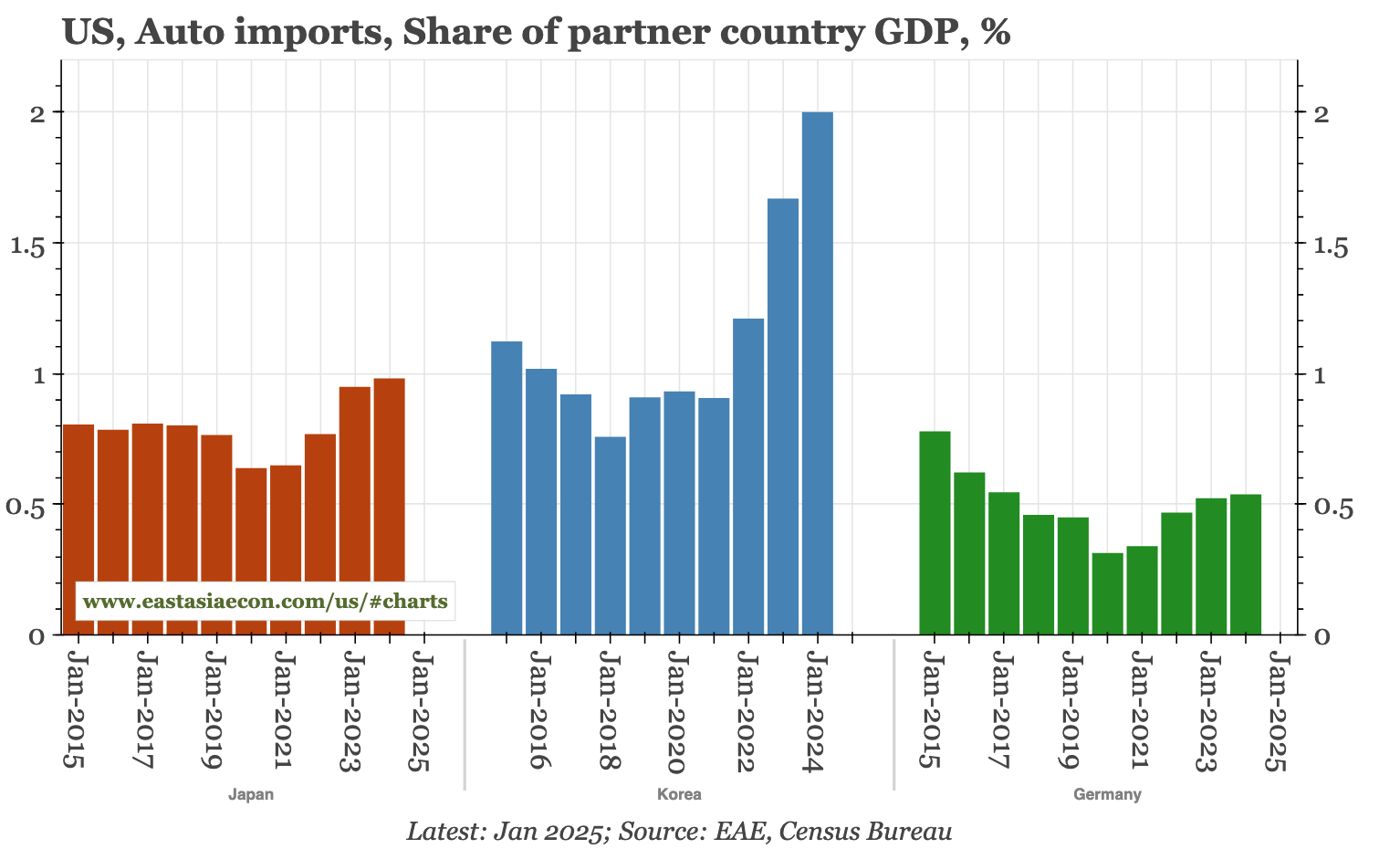

These were the trends even before Trump's real tariff war began. Some of the levies he announced in early April have now been postponed, but apparently, the reprieve won't be permanent. And anyway, even now, the 25% auto tariff remains in place. That's particularly important for Korea, with the big increase in Korean auto exports to the US in recent years lifting sales to 2% of GDP. In Japan, by contrast, the proportion is a more moderate 1%.

In the last full forecasts made in February, the BOK's base case included the assumption that US tariffs on China wouldn't rise much further from the 20% Trump had announced in the early months of this year, and that levies on other trade deficit partners would be smaller still. What's actually happened is closer to the bank's pessimistic scenario, which in February it described as involving:

the US and other countries continue imposing retaliatory tariffs this year. Tariffs are expected to rise significantly this year and remain at elevated levels through next year.

In the bank's assessment, this pessimistic scenario would cut Korean GDP growth to just 1.4% in both 2025 and 2026. That would imply an even larger output gap, and while that wouldn't necessarily affect inflation this year, it would be expected to cut the change in headline CPI in 2026 to 1.6%.

With this as the framework, Trump's Liberation Day seems likely to have made the bank more worried about growth, and less concerned about inflation. In public, at least, it certainly hasn't been anxious about the rebound in services inflation that I've been highlighting in recent months. The bank seems to be assuming that is noise, and the trend of moderating wage growth in Korea doesn't suggest that domestically-generated inflation will continue to rise.

Growth and inflation are obviously the big issues for all central banks when thinking about monetary policy, and that is true in Korea too. However, while macro indicators determine the overall direction of rates, the timing is affected by other factors, and in Korea, three are particularly important: fiscal policy, the currency, and household debt.

Supplementary budget. In January, BOK governor, Rhee called for a supplementary budget of KRW15-20tn. Such a public and specific request for fiscal support was unusual, but the bank clearly doesn't want to have to do all the work of shoring up the economy on its own. Since Rhee made that call, not only have recession bets grown in the US, but Korea has suffered yet another domestic upset with the big wildfires in the south of the country. And yet, the supplementary budget that has now been announced is a modest KRW12tn.

KRW. Since 2024 the currency has been a big consideration for the BOK. To begin with, that was because US rates were above KRW rates and the financial world believed in US exceptionalism. From the end of last year, the currency was dragged down further by the uncertainty created by ex-president Yoon's foiled attempt to impose martial law. With Trump in power in the US and Yoon finally removed from his position in Korea, the downwards pressure on the currency has eased.

Housing. The ebbing of the property upturn that began in June last year was the key factor that allowed the BOK to start its rate cutting cycle in October. In recent weeks, however, house prices have started to rise more quickly again, encouraged by the effective loosening of some buyer restrictions in Seoul. As high property prices are a biparty concern, more macro prudential measures are likely to follow. However, that probably can't happen until after the presidential election in early June. As a result, house prices are probably the key constraint on the BOK cutting this week.