Region – Plaza II

Beijing will be very wary of all the talk of a Plaza II agreement. Plaza I is widely seen as a successful effort to stop Japan's economic rise. That imbalances have nonetheless persisted suggests US macro policy has a role to play, but why would US promises to get fiscal under control be credible?

The original Plaza Accord: short-lived success

Encouraged by the thinking of officials in the incoming US administration, there is big talk in the financial world of a coming policy-led realignment of global imbalances. That hype might be justified, but it would probably be more accurate to talk about re-realignment. After all, the model in mind is the G5 Plaza Agreement of September 1985, the justifiably famous accord that sought to resolve global imbalances via big shifts in exchange rates.

That a new agreement is needed – the "Mar-a-Lago Accord" – obviously implies that the first one didn't work. Indeed, while it was hoped that the Plaza Accord would forestall "protectionist pressures", the rising prevalence of tariffs since the first Trump administration offers ample warning that this time around that opportunity has already passed. And yet, it appears that views on the underlying policy prescriptions haven't changed much. In particular, "exchange rate misalignment" is reported to be a central concern of Scott Bessent, nominated as the next Treasury Secretary.

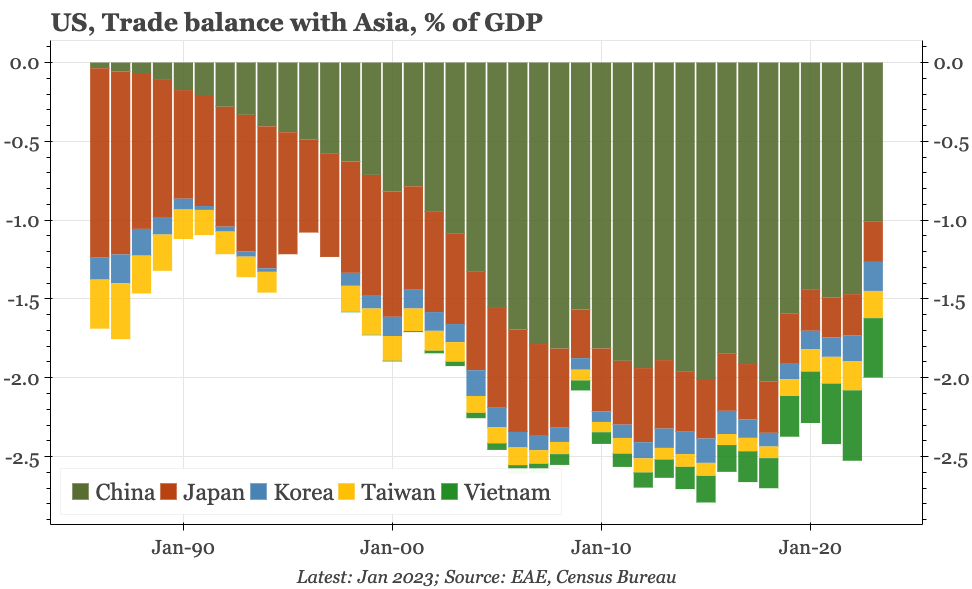

The parallels with the 1980s don't stop there. One side of the global imbalances then, as now, was the US. And while Germany was named as one counterparty on the other side, the bigger focus was Japan. Not being part of the G5, Taiwan didn't feature at all in the accord, but in the 1980s it was also running a big surplus with the US, and was subject to the same forces that subsequently pushed up Japan's exchange rate.

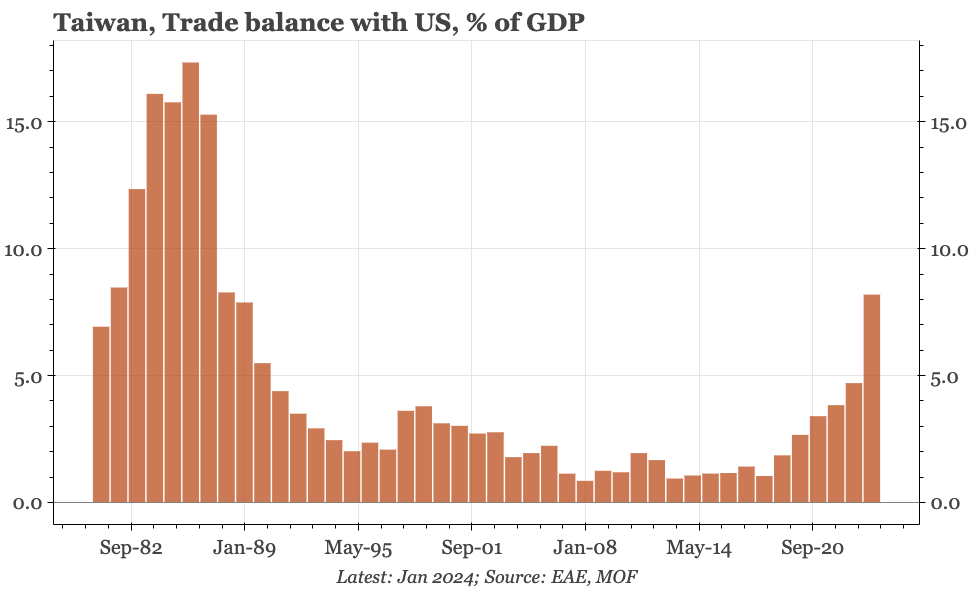

Now, officials in the US once again think Asian economies are central to the economic issues they face at home. Writing before his nomination, Bessent wrote that global trade had been distorted by "the deliberate policy choices of foreign governments, particularly China, but also Japan, South Korea and other export-dependent economies". Taiwan wasn't mentioned, but seems very likely to get caught in the crosshairs given it is now once again running a trade surplus with the US that is more than 10% of GDP, a level last attained in the mid-1980s.

The fallout: falling currencies and supply chain adjustment

Obviously, China wasn't a participant in the 1985 agreement – back then the country had barely emerged from Maoism – but it is central to US thinking now. The role of China means any Plaza II can't be a carbon copy of Plaza I, but it also suggests something very ironic about this latest round of discussion of global realignment. That's because it was the very exchange rate changes of the 1980s that helped create the US's imbalance with China that is such a focus now.

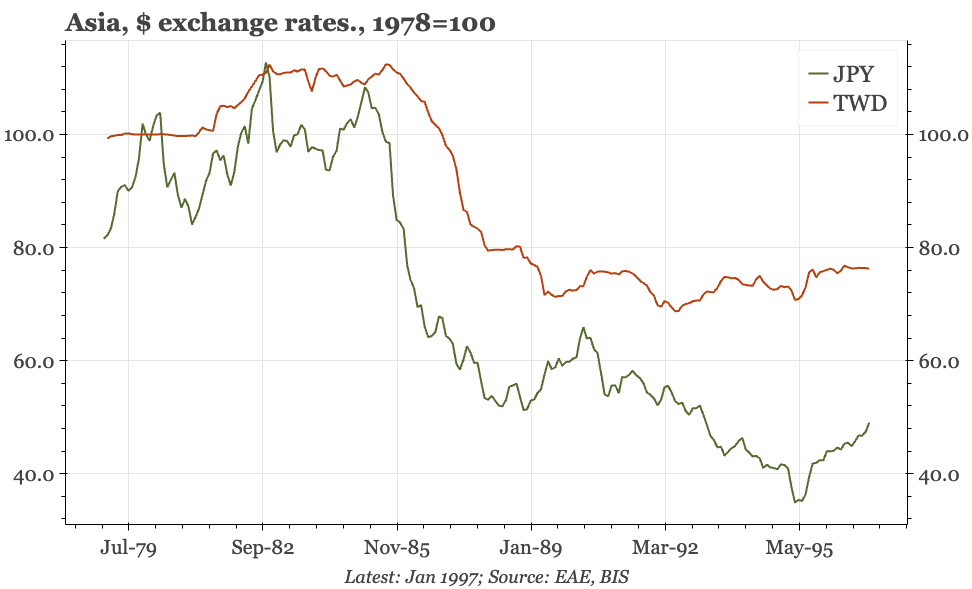

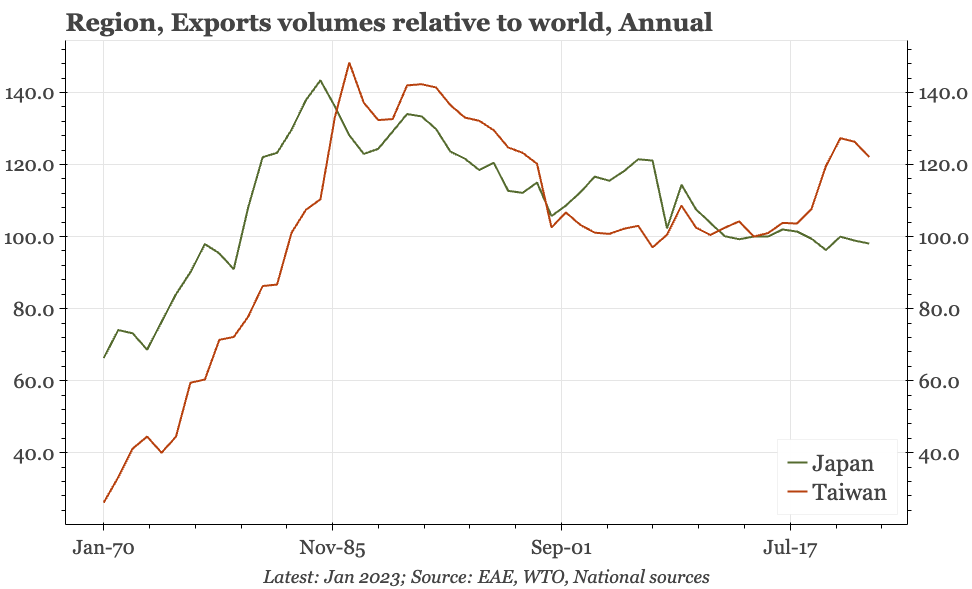

Between 1985 and 1989, the JPY appreciated by 50%, and the TWD by more than a third. On the back of those shifts, there was some improvement in different aspects of the US trade position. But while the Plaza Agreement did mark a fundamental turn in the US trade imbalance with Japan, that was the only change that really stuck. Not only is Taiwan's trade surplus with the US is now as big as ever, but so is the US's overall deficit.

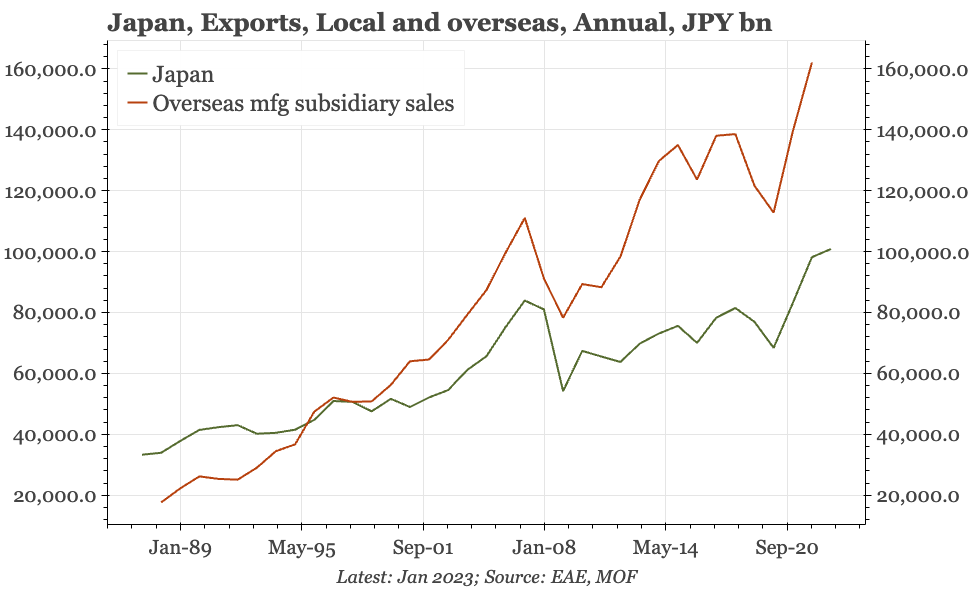

Needless to say, in this overall picture, China has replaced Japan as the biggest overseas counterparty to the US deficit. There are many reasons for the rise of China. But one of them is the movement there of manufacturing from Taiwan and Japan, shifts that were hastened by the sudden shock to competitiveness delivered by the exchange rate changes of the 1980s. Indeed, the shifts in manufacturing were as significant as the moves in the currencies. Japanese and Taiwanese firms started to move production in the late 1980s, ten years most of Taiwan's computer production was on the other side of the Strait, and by the 2000s more than 50% of China's exports were being produced by foreign firms.

Supply-chain restructuring wasn't the only economic response in Taiwan and Japan to the dislocation of the 1980s. Another – as a trend in Taiwan, but more fitfully in Japan – was the reversal of the currency appreciations of the 1980s. Between the peak in 1989 and 2009, in real effective terms the TWD steadily depreciated, and despite all the very real economic development achieved since, is now still 30% below the all-time high. The JPY, meanwhile, is now cheaper than at any time since the 1960s.

Given the big economic dislocations of the 1980s, some currency weakness thereafter wasn't unreasonable. But especially in Taiwan, this recalibration went much too far. The continued weakness of the currency has contributed to clear imbalances in Taiwan's economy: a huge current account surplus, an over-sized manufacturing sector, and weakness of household USD incomes. From the point of view of some Asian economies, external pressure that forces some appreciation would be helpful.

China today: weak currency and strong exports

But that doesn't mean China in particular will buy into a new Plaza-type framework, and without the participation of the world's second-largest economy, meaningful global realignment won't be possible. While Japan's economic malaise after the 1990s wasn't helped by mistakes made by policymakers in Tokyo, it is easy to understand why the main lesson for Chinese policymakers who have studied the period is to avoid being bullied by the US into big economic realignments. After all, out of the three economies that were the leading parties to the Plaza Accord, only the US is now still strong.

That the 1985 agreement effectively ended Japanese economic development but didn't resolve US imbalances feeds into another line of thinking that is prevalent in China: the issues that Bessent and others are once again highlighting are the result not of Asian exports, but of US policy choices. This stance has become more common in China after the global financial crisis and the covid pandemic – and the disruptions caused by the US policy response to both. A clear exposition of this view can be seen in a 2021 speech by the then party secretary of the PBC, Shu Guoqing, in which he criticised the super-stimulus", "money printing" and "so-called unilateralism" of the US and its western allies.

Clearly, there wasn't universal admiration in Japan for the US in the 1980s, but outwardly at least, the international policy environment back then was cooperative, with the Plaza Agreement presented as "win-win". Now, the incoming US president is openly "America first" on economic issues, and on foreign policy has surrounded himself with avid China hawks. This context will make Beijing more wary still of any push that Bessent and others now make for global realignment.

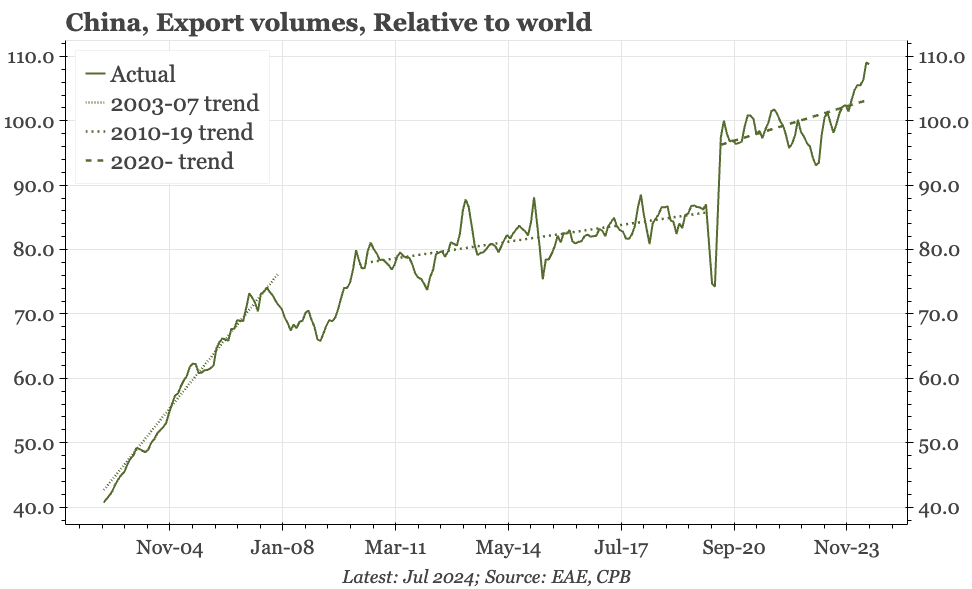

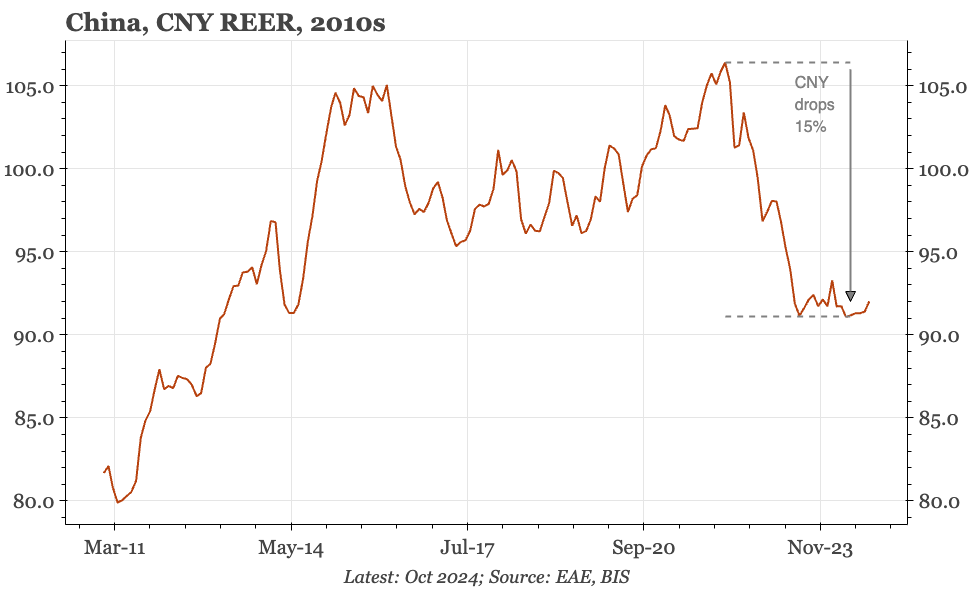

Of course, with protectionism transforming from the threat of the 1990s to the reality of today, Trump's pledge to impose a 60% charge on all products coming from China is more than just a warning. Implementation will be damaging to China, and is clearly a change that policymakers in Beijing would rather avoid. That said, the first round of Trump tariffs didn't deliver the sudden shock to China's exports that the currency appreciations of the 1980s did to Japan and Taiwan. Indeed, China's exports are now 50% higher than before Trump took office the first time around, and through 2024 have continued to show very strong momentum. One reason is the depreciation of the CNY, which in recent months in real terms has been weaker than any time in the last ten years.

Just as currency weakness hasn't been helpful for the household sector in Taiwan, nor it is welcome for China's longer-term economic development. Currency appreciation would be a very useful way for the strength of China's export sector to feed into the domestic economy. That, however, is more of a structural consideration. With China already struggling with deflation, forced currency appreciation now would be especially painful.

US options: carrots as well as sticks

Bessent talks about the need for the US "to tackle its own contribution to global imbalances by reducing its unprecedented budget deficits". Given the widespread belief in China that the US has been creating its own problems, such a pledge would indeed need to be part of any global agreement. However, it is unlikely that talk alone will be sufficient. After all, US pledges to control the deficit were an explicit component of the Plaza Accord, but, as with the persistence of Asia's trade surpluses, that US fiscal policy remains an area of contention now shows there wasn't continued follow-through.

Even without the broader tensions between the US and China, this history would create a deficit of trust. There is no external body to enforce US compliance with any agreement – and even if there was, the US would never sign up to it. As a result, from Beijing's perspective, all this talk of global realignment is one-sided, making it more likely that China refuses the sort of currency changes that the US wants to see. While that probably makes tariffs inevitable, China's officials will be thinking that the imposition of high and universal tariffs won't just damage targetted economies, it will hurt the US too.

Can all this be avoided? Perhaps, but at a minimum, it likely needs the US to be offering carrots along with the stick of tariffs. Rather than just threats, the Trump administration would need to come up with something that Beijing thinks makes a US-led realignment attractive for China too – the "win-win" that is such a favoured phrase in Chinese diplomacy.

Outwardly, that would be contrary to Trump's America First, zero-sum approach. However, if the president is the dealmaker that he claims, then he would presumably recognise that something needs to be offered. For Xi Jinping, that's likely the grand bargain discussed on the fringes of the first Trump term, involving China going along with US demands on the economy, in exchange for the US yielding to China's demands on security and military affairs in the Pacific. By offering that, Beijing might be able to conclude that US economic demands aren't just about stopping the rise of China. But with hawks dominating the US foreign policy establishment, such a bargain seems unlikely – while also signalling to Beijing that US economic policy isn't really about global realignment, but rather ensuring US continued dominance.