Taiwan – how to dispose of USD100bn?

There's rarely much interest in Taiwan macro. But 2025 could be different: with post-2020 domestic economic lift-off, and the return of Trump, the circumstances that have kept the TWD undervalued for 20 years might be changing. This is a detailed chart pack looking at the issues involved.

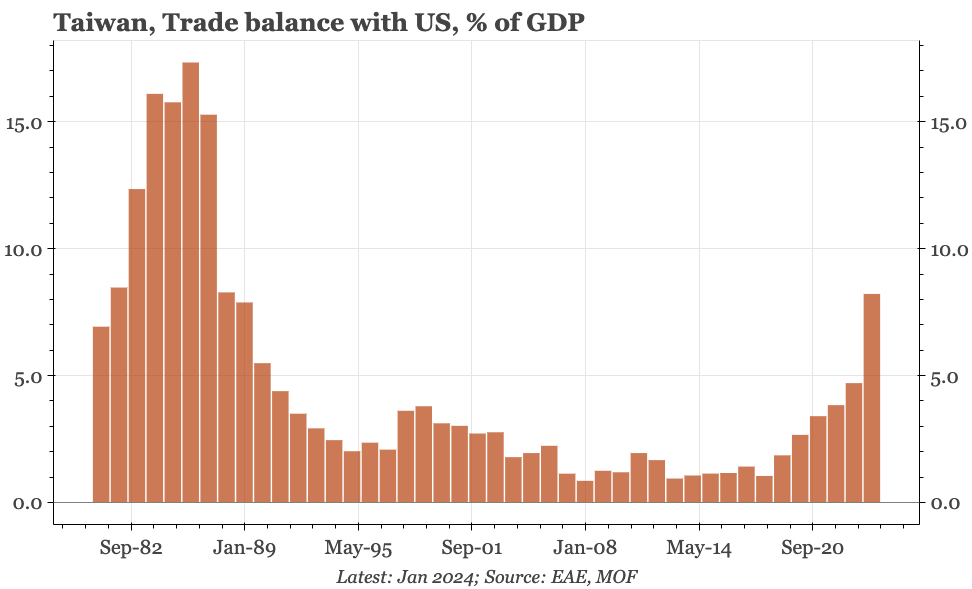

Before being nominated as Treasury Secretary, Scott Bessent made it clear that one of his areas of focus was global imbalances. Obviously, in this, China is the biggie. But the post-child for sustained imbalances is Taiwan. After the adjustment following the Plaza Agreement in the 1980s, Taiwan's overall current account surplus, and its bilateral trade imbalance with the US, are once again back to double-digit levels relative to GDP. Taiwan's net foreign asset position ranks among the top five in the world. If it wasn't for the threat of invasion – a risk that clearly can't be forgotten – the TWD would be considered a safe haven currency. And yet, despite this change, the TWD remains as weak as it once 20 years ago.

That for much of the time since the early 2000s Taiwan has been close to deflation was one factor that allowed this situation to sustain. The central bank has had little reason to raise interest rates, making nominal returns available overseas look more attractive. However, these relative returns clearly wouldn't have been so high if the currency had been appreciating, meaning it is important to understand the mechanics of the flows that have kept the TWD weak. Before the global financial crisis, the recycling of the current account was done by the central bank. Since then, it is private investors that have done the heavy lifting, in the form of Taiwan's life insurance companies before 2020, and corporates more recently.

These outflows have been enabled by regulatory changes. That is most obvious with respect to the lifers, where an initial 45% ceiling on their foreign expose broke down around 2015, and regulators continue to take steps to reduce hedging costs. As a result, the lifers fx book has grown from basically zero in the early 2000s to almost USD1trn now. Given that size, the foreign investments of lifers have been critical in offsetting Taiwan's current account inflows and so helping keep the TWD stable. But there has been a cost, with these and other private firms taking on more fx risk on their balance sheets.

It is impossible to know when the Taiwan authorities start to think that the financial stability risks from this exposure become too great to bear. Presumably, it should be worrying someone in the government. Regardless, there are other forces now pressuring Taiwan's fx strategy. One is Taiwan's economic take-off since covid, a shift that means inflation is unlikely to return to the ultra-low pre-2020 levels – and if inflation is going to be higher, interest rates will be too. Another is the incoming US administration. With an eye on Trump's bugbears of foreign free-riding and big trade imbalances, Taiwan has already been talking about importing more weaponry from the US. At only round 2% of GDP, Taiwan's military spending is low. But even if that doubles, it will do more than make a dent in Taiwan's external surplus.

Of course, it is possible that the current status quo sustains, with the US economy remaining strong, continuing to attract capital out of Taiwan, while domestic regulators turn a blind eye to the increasing fx risk that private investors thus accumulate. But there are also two easily-imaginable scenarios in which the status quo breaks down. One is where a US slowdown dampens potential returns and so discouragers private investors from taking on US risk. Given Trumpian politics, I doubt the central bank could then step in once again to take the lead in recycling the current account. Equally, if domestic inflation remains sticky while the US puts political pressure on Taiwan, it also becomes possible to imagine a real structural shift in the TWD exchange rate.