Taiwan – first to cut?

The industrial cycle is slowing, consumer confidence is weak, and a modest rise in inflation has likely peaked. Given all that, Taiwan is well-placed to be the first regional economy to cut rates. The risks are yet more aggressive Fed hikes, or a powerful economic turnaround in China.

Taking stock

The end of the boom

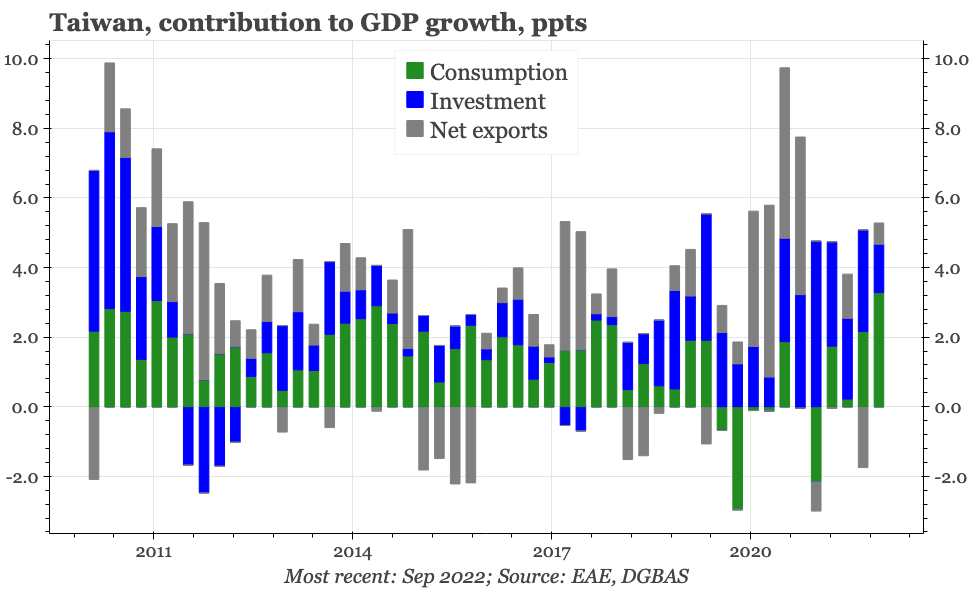

Taiwan's economy boomed during Covid. Indeed, it is perhaps the only economy in the world to have experienced a step-up in GDP during the pandemic, a lift that has yet to dissipate. That was driven by the global surge in demand for tech, especially the semiconductors produced by TSMC. The export boom wasn't offset by a collapse of domestic demand. Consumption was certainly disrupted by covid, but in broad terms, Taiwan managed to control the spread of the virus until most of the population was vaccinated. As a result, the government was never forced to implement a formal lockdown, either localised or national.

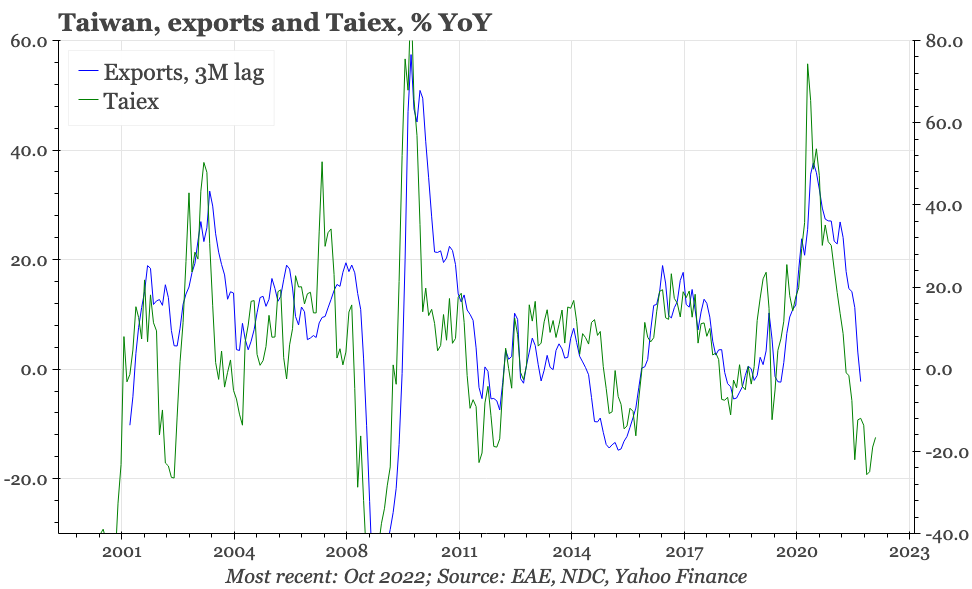

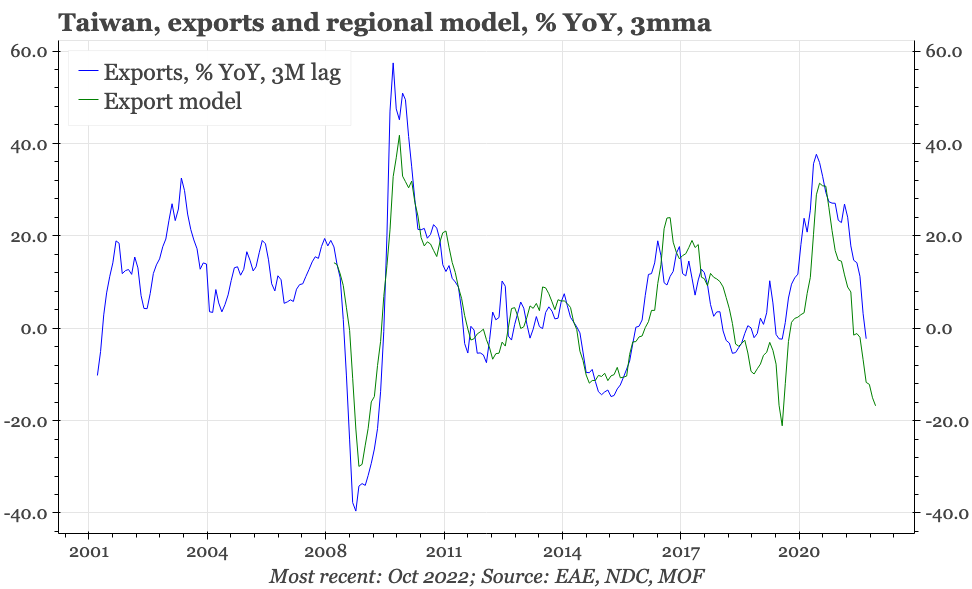

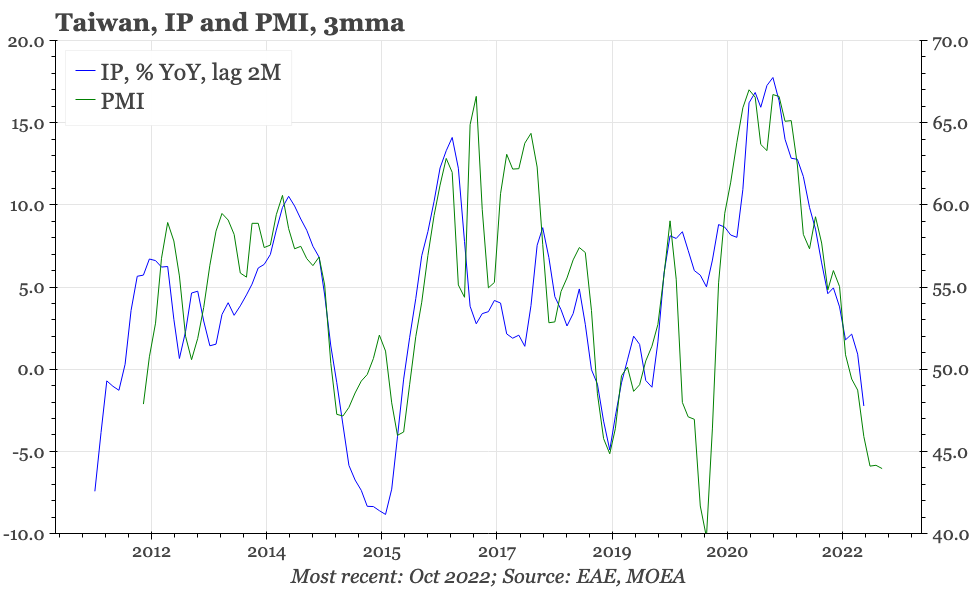

But that boom is now over. On a headline basis, export growth peaked at almost 40% YoY in May 2021, steadily slowed thereafter, and in October this year turned negative for the first time since June 2020. The PMI has looked recessionary for a while, and November produced no respite. The official version dropped to 43.9, the lowest since this particular survey started in 2012. S&P Global's PMI for Taiwan ticked up from October, but at 41.6, remains far below the 50 level that would indicate expansion. Overall, all the evidence points to Taiwan's manufacturing sector enduring the worst downturn since the global financial crisis in 2008.

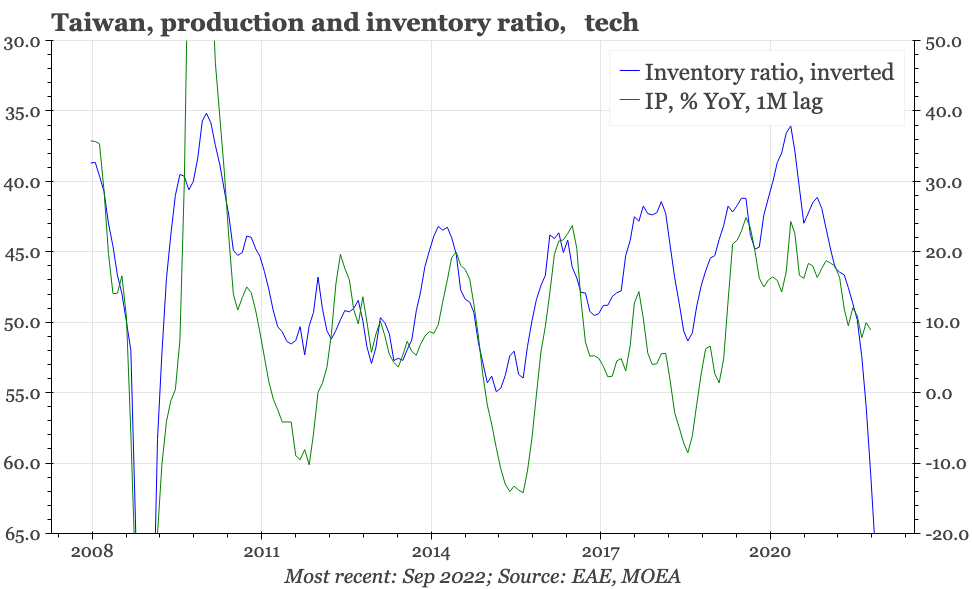

Leading indicators aren't suggesting a near-term recovery. Our regional export model, which has proven a good guide to the regional trade cycle in recent months, continues to point down. Similarly, export orders in the official PMI dropped again in November. A big reason for this deterioration is the build-up of inventories throughout the manufacturing supply chain. The shipments:inventory ratio in the tech sector in the last few months has been as sharp as during the big slumps in 2001 and 2008. That suggests a lot more downside in IP growth during the next few months.

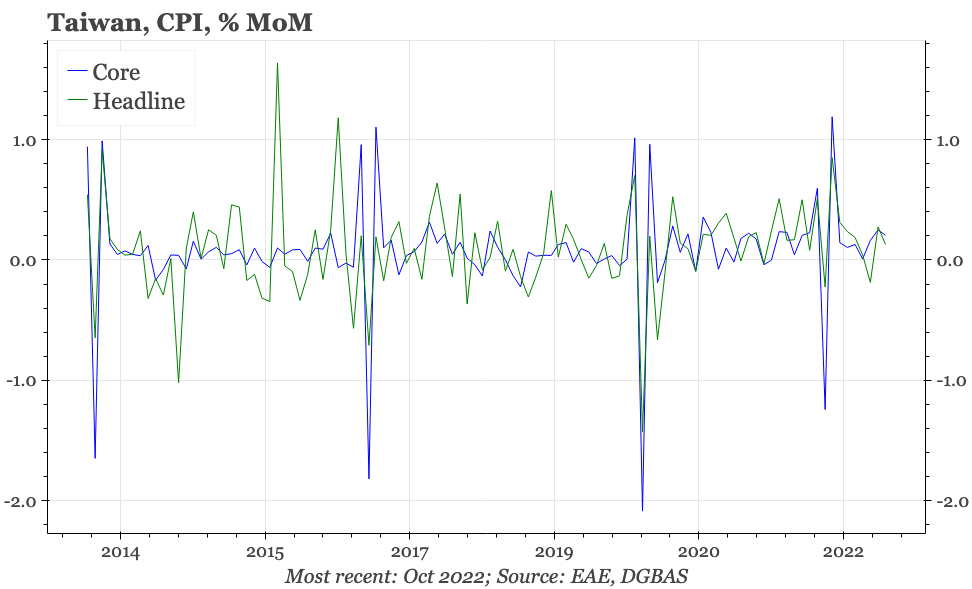

Low inflation, high productivity

This is all striking because even during the boom, Taiwan never experienced much over-heating. Headline CPI inflation did rise, but peaked at less than 4%, a rate that wasn't even as high as experienced in 2008. From a historical perspective, the rise in core inflation is more notable, but still hasn't exceeded 2%. Moreover, unlike in, say, Korea, it isn't obvious that this rise in anything more than the increase that tends to accompany economic recovery; on a MoM basis core isn't particularly elevated. In any case, as with overall activity, leading indicators for inflation are pointing down. That's particularly apparent regarding prices in the PMI, but is also true for oil prices.

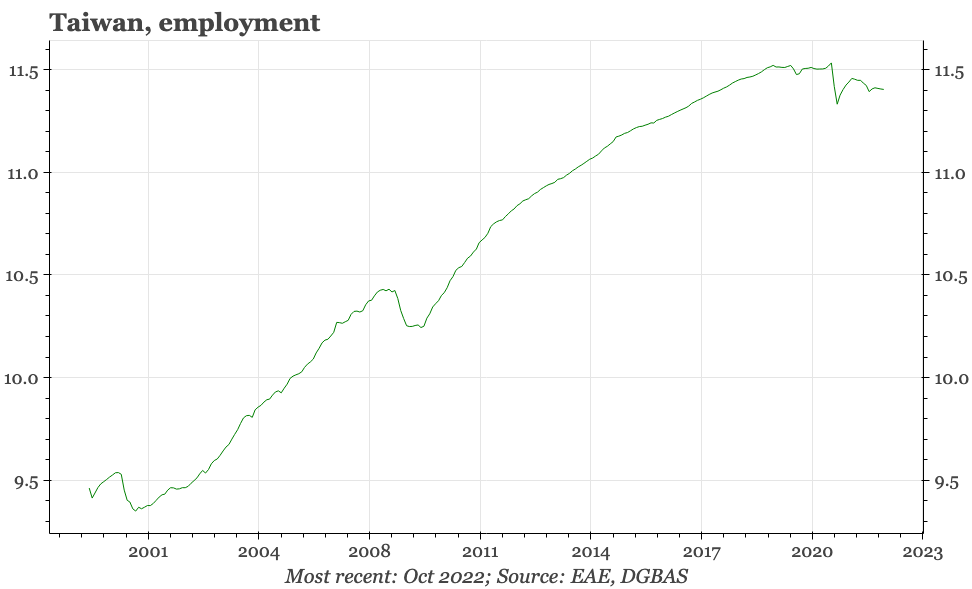

Admittedly, these leads are best at capturing trends in manufacturing and import prices, so there is a risk they understate inflation pressure emanating from services and the domestic economy. Here too, though, there is little signs of a problem. Employment fell during covid, and remains below the pre-pandemic level. At 3.6%, the unemployment rate is low, but not dramatically so; unemployment averaged 3.8% in the five years heading into the pandemic (and in the 1990s was almost always below 3%).

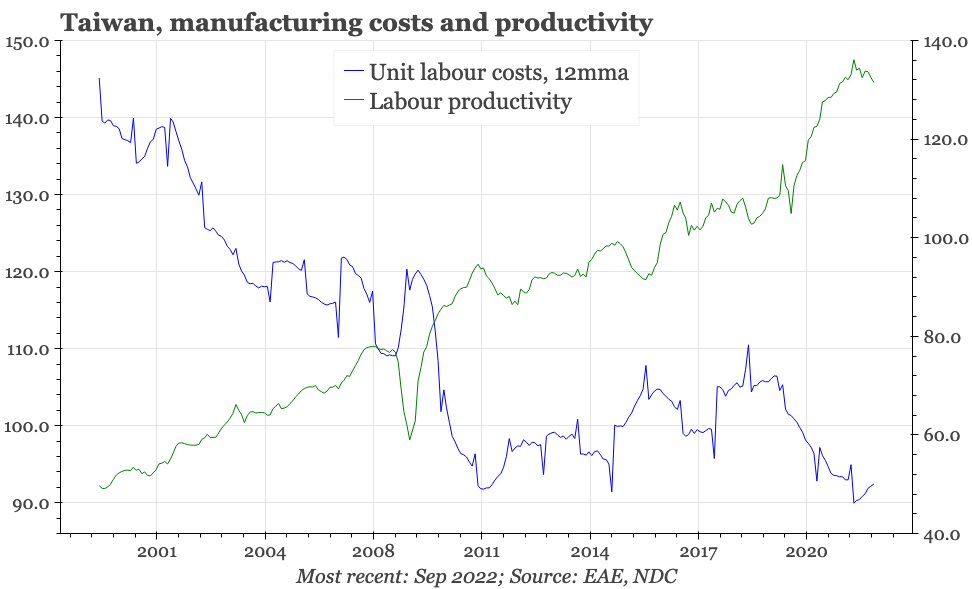

So, Taiwan has experienced a big jump in output, but without a corresponding rise in employment. The implication, of course, is a big improvement in productivity, and this is precisely what the labour data suggests has happened. According to official statistics, between December 2019 and early 2022, labour productivity in manufacturing surged by 25%. Even after a bit of a moderation in the last few months, the rise since before the pandemic began remains dramatic.

Financial strength

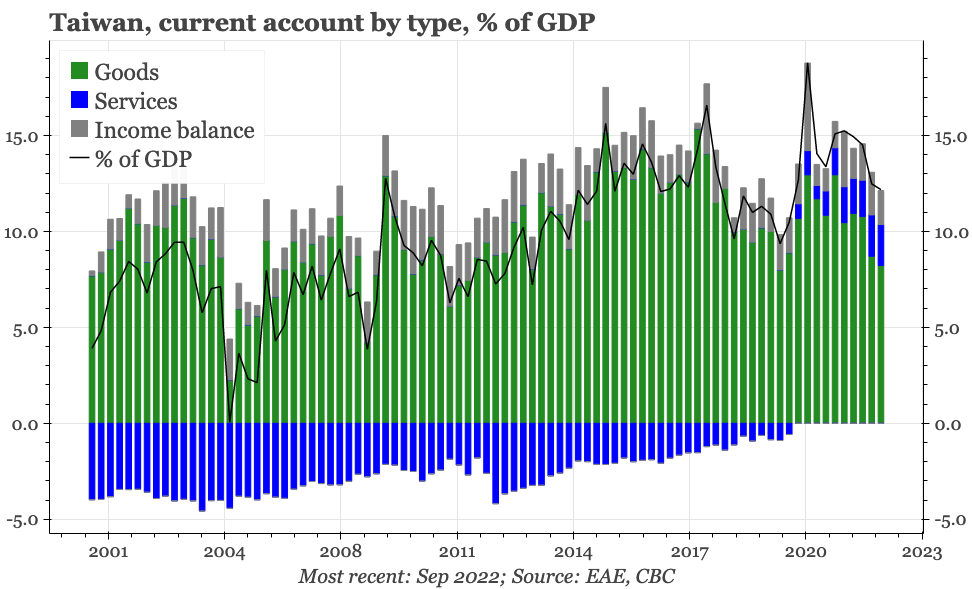

With the current account surplus going into the pandemic so big, Taiwan's international competitiveness was already sharp. With the flip side to the rise in labour productivity being a fall in unit labour costs, there is certainly no reason to think that competitiveness is now being eroded. The external surpluses have deteriorated as the import fuel bill surged. But unlike in Korea and Japan, Taiwan's trade balance has remained firmly in the black, and that in turn kept the current account surplus at more than 10% of GDP in Q3.

The large external surplus has been an important source of support for the currency in recent years. Arguably, the superior management of the covid pandemic has now added another. Without the need for lockdowns, Taiwan hasn't had to resort to the sort of extreme fiscal largesse that has been so common elsewhere. As a result, IMF data show that Taiwan's public sector debt coming out of the pandemic remains under 30% of GDP, lower than it was before covid first emerged.

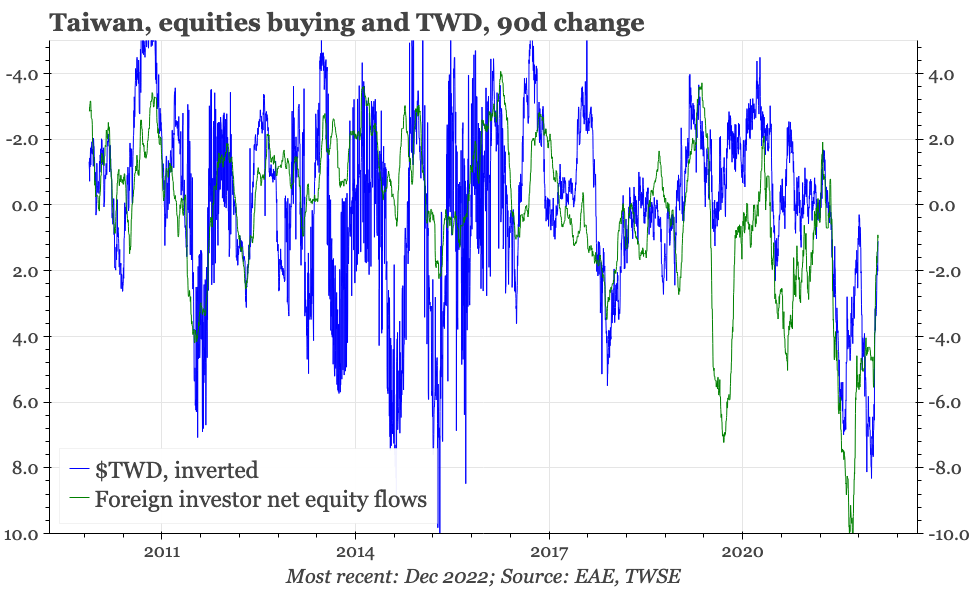

These structural factors don't prevent cyclical fluctuations in the currency, and the TWD has depreciated against the USD since throughout most of 2022. That isn't surprising. For one thing, there's the strength of the USD. In addition, the TWD usually weakens with a deterioration in the export cycle, with one driver being falling corporate earnings, a sell-off in the tech-heavy stockmarket, and so portfolio outflows. However, the fall in the TWD has been modest compared with the weakening of other currencies, and that makes sense given the strength of the external and domestic financing positions. As a result, currency depreciation hasn't added much to the anyway modest inflation pressure that Taiwan has been experiencing.

Why wouldn't the CBC cut?

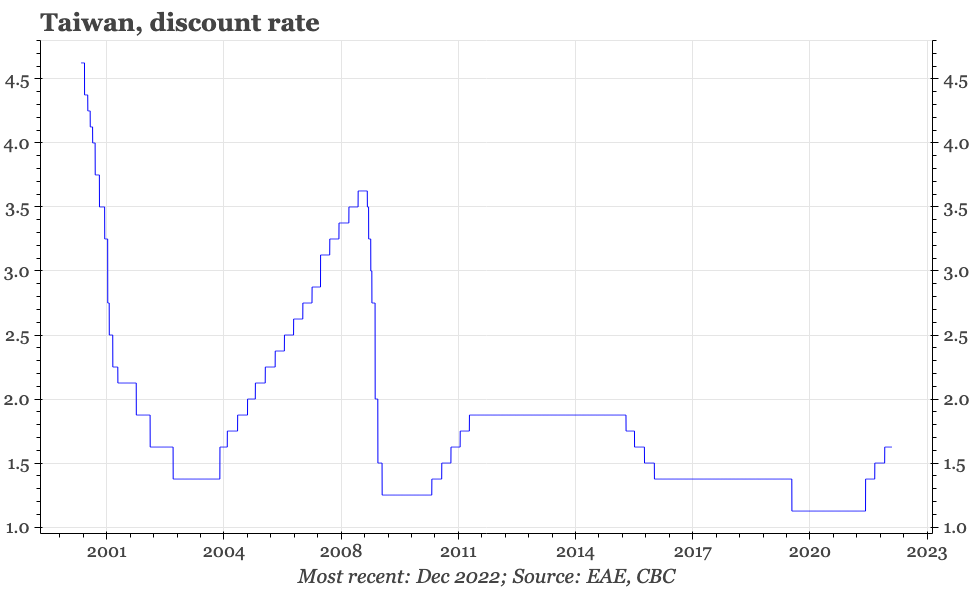

Corresponding with the modest rise in inflation, tightening by the CBC, Taiwan's central bank, has been restrained in the last couple of years: the last hike in September took the policy rate to 1.6%, up from 1.1% in March. With exports now contracting and inflation likely to have peaked, the question so not whether rates go higher from here, but whether the CBC will be the first to central bank in the region to cut.

To be frank, that isn't the most accurate way to portray Taiwan's policy debate: if the CBC does cut, it won't be the first, because the People's Bank of China has been reducing interest rates ever since 2019. And although further sharp rises in US rates would reduce the CBC's room to cut, it is China that probably represents the biggest risk to the direction of rates in Taiwan.

This is because it is the dramatic cyclical slowdown in mainland China that has been the biggest driver of the sharp deterioration in Taiwan's exports. The authorities in Beijing now look increasingly keen to bring that economic pain to an end, announcing policies to end the property squeeze, and to offer a path out of zero covid. These are important changes, particularly because they are happening at a time when some of the economic indicators in Taiwan, while not improving, have shown tentative signs of not worsening further.

As always, then, monitoring China is important for understanding Taiwan's economic cycle. Still, it seems optimistic to think that China's economy can now both recover, and in so doing also seamlessly offset a likely slowdown in US and EU demand, quickly ending the recession now being experienced in Taiwan's manufacturing sector.

The other hope would be a different sort of hand-off in growth drivers, this time from the export sector to domestic demand. The reasoning here would be that consumption in Taiwan usually in fairly close synch with the export cycle, but that this normal pro-cyclicity has been disrupted by covid. That then, perhaps, leaves room for consumption to support growth even as exports slow. Q3 data did give some hope to think this handover was occurring, with consumption making the largest contribution to GDP growth since 2004. However, a bit like the China hope, this seems optimistic, with consumer confidence measures falling quite sharply in recent months.