The China Diviner

The government's view that it is homebuilders not homebuyers who are the "speculators" has big implications for where the property cycle goes next, and what that means for the economy.

The demand side of the property downturn

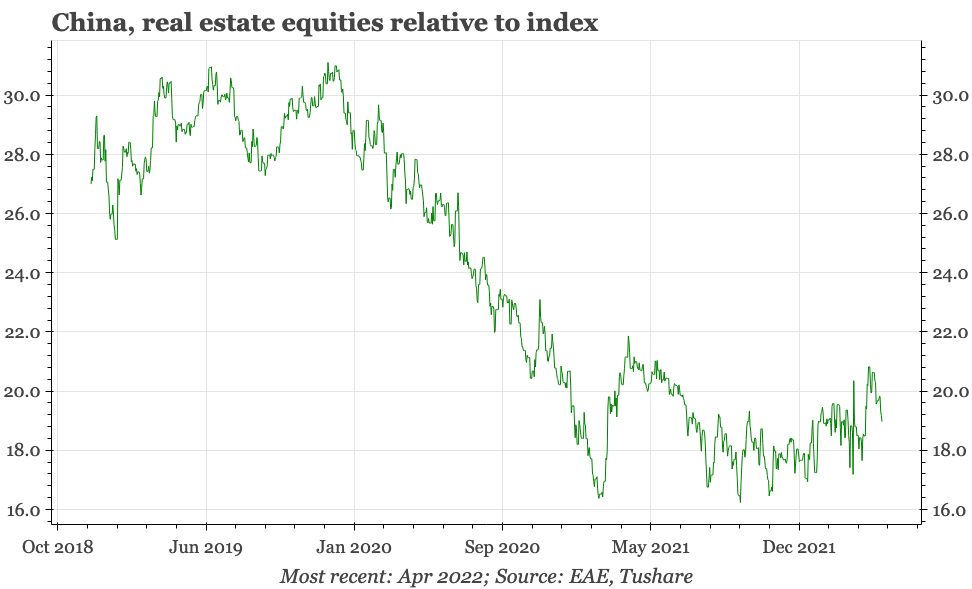

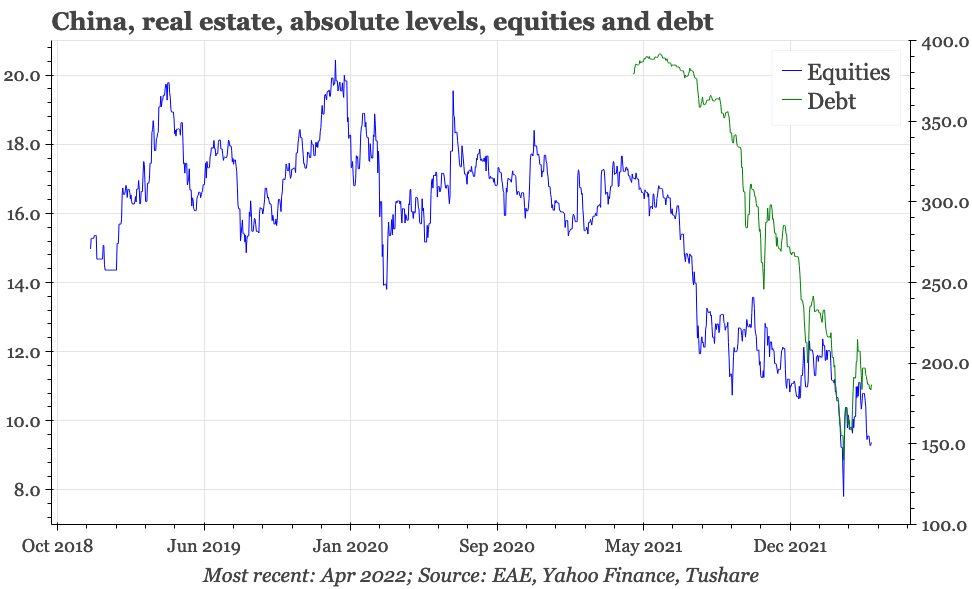

For policymakers in Beijing still dreaming of achieving the 5.5% growth target for 2022, about the only cause for optimism to be found in the market carnage of the last few weeks is that it hasn't been led by property developers. In fact, for the first time in a while, homebuilders have been outperforming.

To be clear, it has taken the probability of a lockdown of two of China's biggest, richest cities - with all the negative impact that has on services activity in the broader economy - to produce this outperformance. Whether looked at from the perspective of debt or equity, the developer sector remains very fragile in absolute terms.

However, the renewed covid crisis is producing an intensification of the incremental policy easing to homebuilders that began in September 2021. There are reports that there isn't a clear consensus in Beijing on how far loosening should go, but last week's latest window guidance meeting that was convened by the PBC with the commercial banks reportedly included the strongest instructions yet for specific loosening towards developers.

Homebuilders, not homebuyers, are the "speculators"

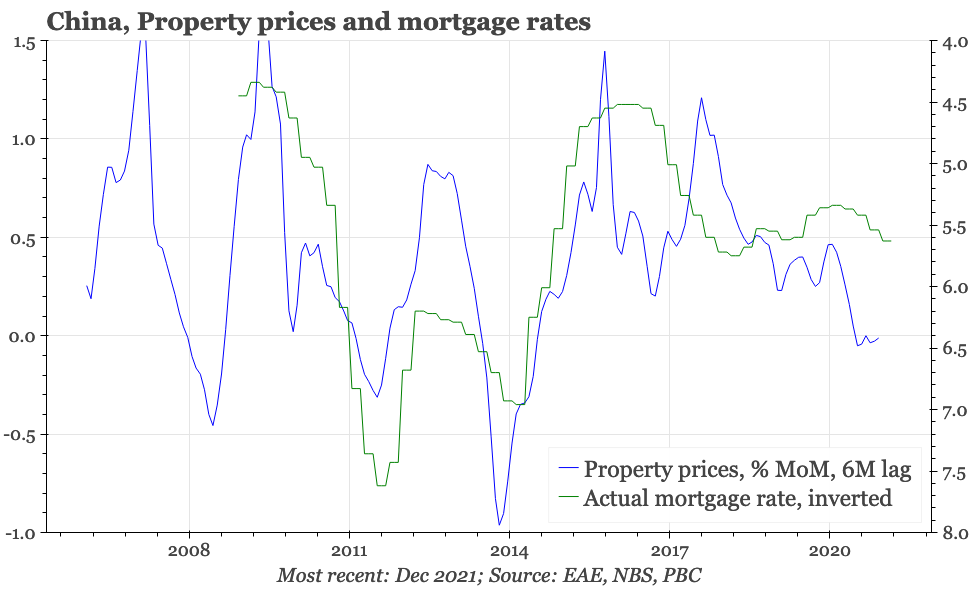

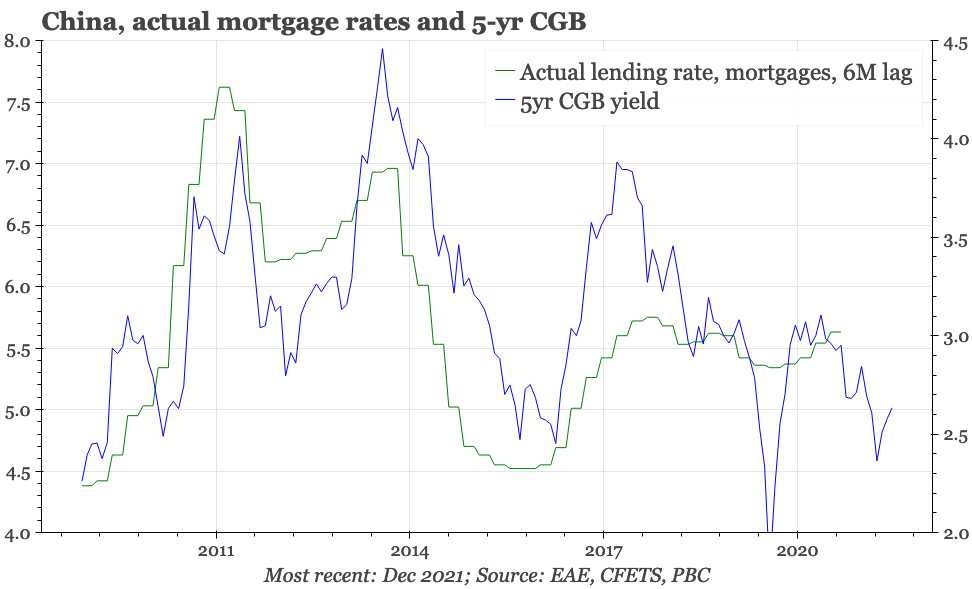

If perhaps not a reversal, there is then at least some easing of the financial squeeze on developers. And it has been developers that have been the main target of property tightening since 2020. Mortgage rates did rise and some other specific measures were used to cool end-user demand for property. But according to data from the central bank, interest rates for home buyers have only reached 5.6% in this cycle, lower than the 5.8% peak in 2018, let alone the 7.6% reached in 2011. Rather than concentrating on home buyers, the centrepiece of Beijing's policy towards property over the last two years was constraining developers within the so-called three red lines, a policy that was launched in August 2020 with the aim of reducing leverage.

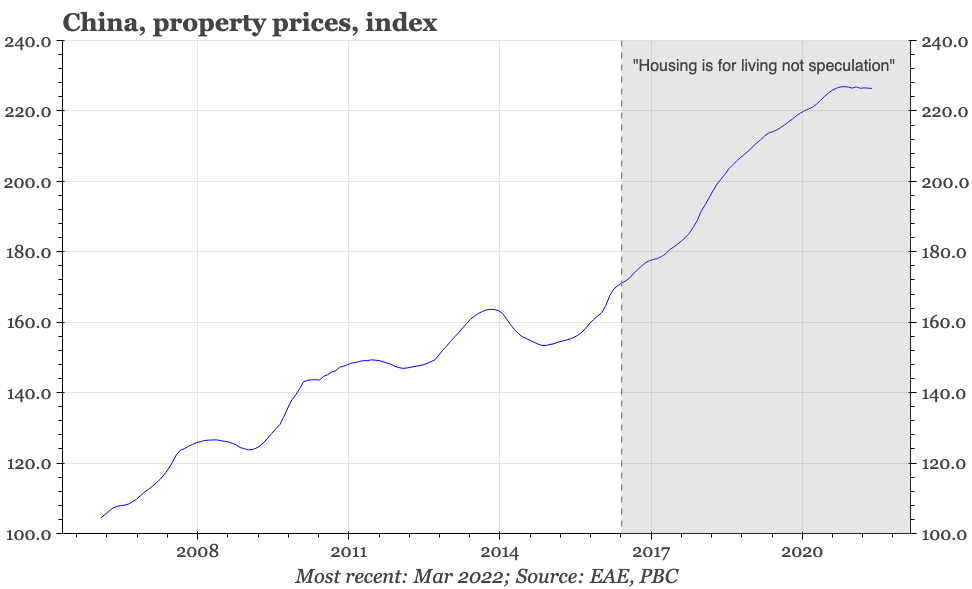

This focus on the supply side is notable because even now, the slogan most commonly associated with the government's thinking towards the property market is Xi Jinping's 2016 announcement that "housing is for living, not speculation". On the (increasingly rare) occasions since 2016 when this phrase has been excluded from the high-level statements that periodically discuss macroeconomic policy, investors have tended to take it as a sign that policy towards property is loosening.

In the developed economies, where most of the housing market involves buying and selling of existing homes, price bubbles tend to be inflated by the en-masse behaviour of buyers (enabled by the excesses of the financial sector). But in a housing market like China's, which since its emergence 20 years ago has revolved around both the construction and sale of new apartments, there hasn't just been opportunities for buyers of finished properties to "speculate". For home builders too there's been huge amounts of money to be made - and sometimes lost - participating in the wholesale transformation of China's urban areas. Collectively, Chinese homebuilders have delivered over 100m apartments in the last twenty years. So clamping down on developers isn't entirely inconsistent with the ideal of making the housing market less about finance and more about "living".

An anti-speculation campaign that doesn't lower prices

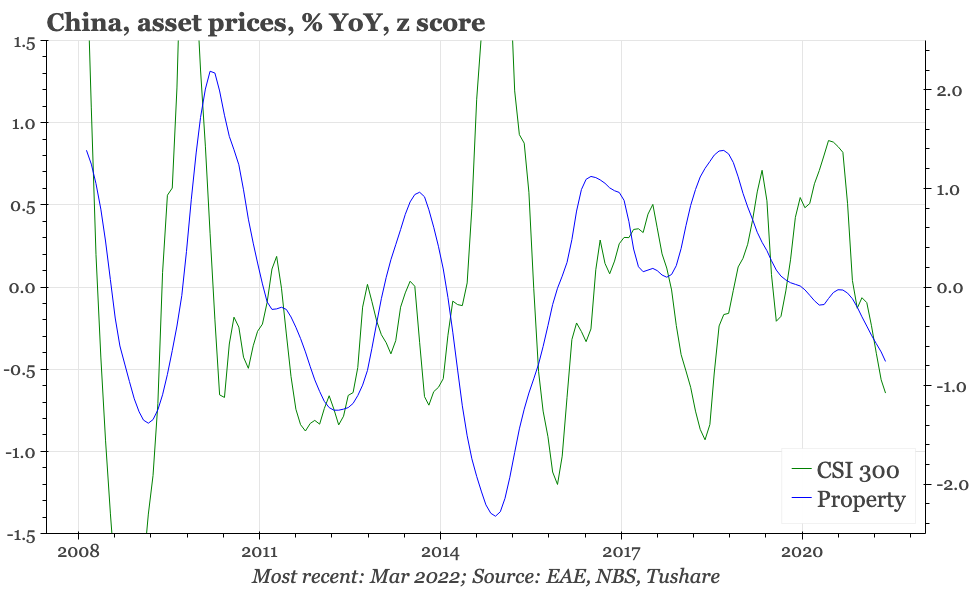

Still, if one of the features of "speculation" is rising prices, then it is still somewhat jarring that Xi Jinping's first pronouncement of his now-famous call to cool the property market actually coincided with the early phase of the most sustained period of property price inflation in China since at least the early 2000s.

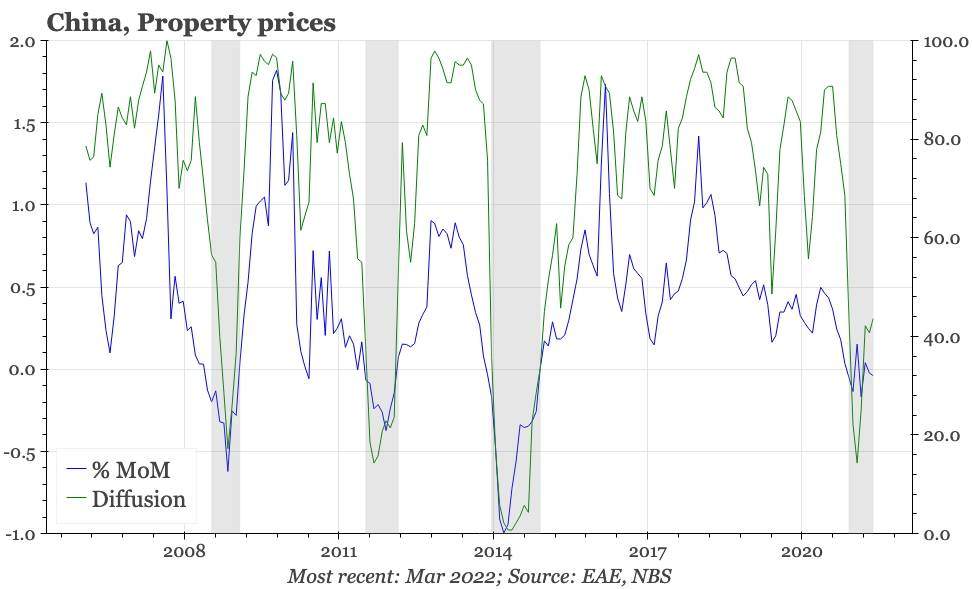

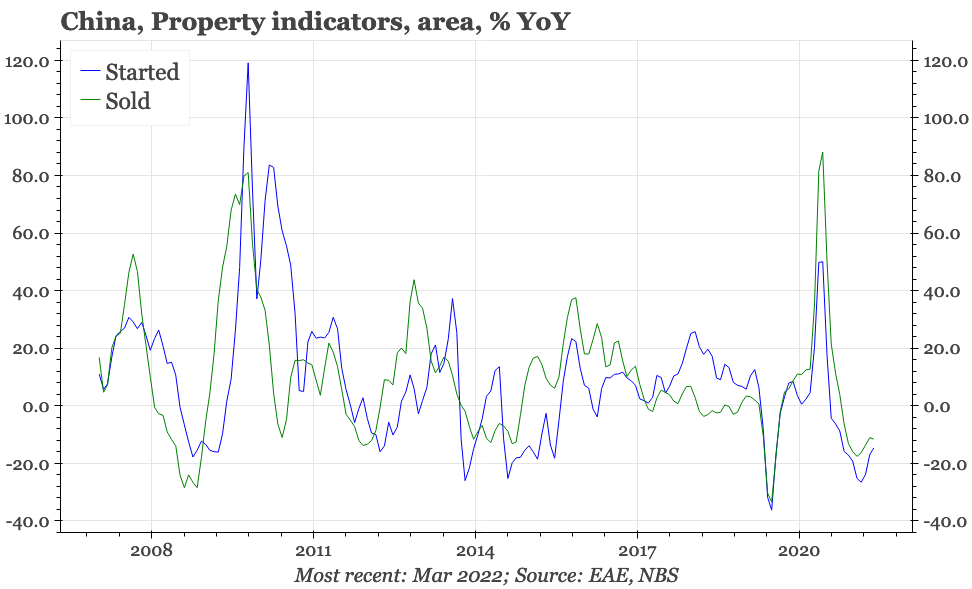

To be sure, the specific measures that came with the announcement that "housing is for living, not speculation" did cool the quite rapid price inflation that was building at that time, but the policy hawkishness didn't kill the cycle. Starting in May 2015, the average price change in the 70 cities surveyed by the statistics bureau was positive for 76 consecutive months, delivering a cumulative increase of almost 50%. That is almost certainly an underestimate, with reports that political pressure on local officials to hold down housing costs resulted in manipulation of reported prices. But even official data show that in some individual cities the rise has been quite a bit more (though importantly from a political perspective, it hasn't been in the first-tier cities where recent price rises have been sharpest). By way of comparison, in the recovery from the sharp downturn in 2008, a period in which there definitely was a good deal of end-user speculation, average prices rose for a more modest 31 months, in total increasing by just a bit over 20%.

Feeling the effects of the tightening campaign, this latest property price cycle that began in 2015 did finally come to an end in September 2021. But in the months since, official data show prices have fallen by a total of just 0.8%, a pace that at least before the latest covid shock, had already shown signs of bottoming out. Price corrections in previous Chinese property cycles have tended to be short-lived and mild, with some downside hidden by the usual attempts in downturns to show "stability" and so hide the extent of the damage. There's reports this time of developers being restrained from cutting prices directly, and so instead resorting to gimmicks like free cars to boost house sales. But again, these kinds of strategies tend to be a feature of all downturns in China, so even allowing for it, the current fall has been shallow: in the last down cycle in 2015, prices fell a cumulative 6%.

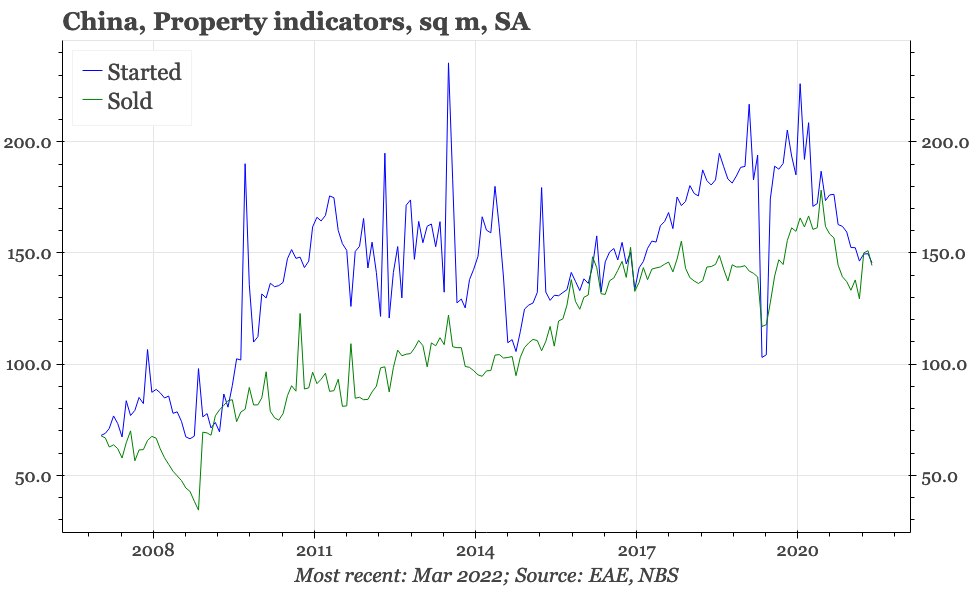

This even milder-than-usual correction in prices looks out of place with the much bigger-than-typical fall in property sales. The official numbers on housing transactions aren't of great quality, being published only on a year-to-date basis, and with no separate data released for January. The overall impression though is that the fall in property sales this time around has been as big a fall as has been experienced in any previous cycle.

That this hasn't impacted prices much is, again, partly due to data issues. But it is also because as much as demand has shrunk, so has supply, a parallelism that reflects the supply side characteristics of both recent government policy, and the property market more generally. Perhaps needless to say, severely constraining the finances of the home-building companies isn't an obvious way of boosting the supply of property. Of course, the government would have been hoping that developers needing to pay back debt to stay afloat as businesses - a real consideration recently - would speed up development of any projects they have on hand. But it seems some developers have lacked the money even to be able to do that, and anyway, a feature of property cycles in China has been that demand and supply tend to move together.

This doesn't necessarily mean that supply is now, or was in the past, driven by demand. In the current cycle it is entirely possible that supply has been more important in determining demand. While media discussion of the impending implosion of the Chinese property market has been more common overseas than onshore, the pressure that developers have been under has been known widely enough in China. With so much of the primary market involving pre-sales, where developers sell property off-plan for a deposit with a promise to deliver later, it is not hard to imagine that this knowledge has made potential buyers more cautious lately. Why risk giving your life savings as a downpayment to a developer that might be out of business before they can deliver your new home?

An anti-speculation campaign that doesn't raise interest rates

Overall then, I'd guess that 80% of the tightening since 2020 was focused on developers. That characterisation is hardly scientific, but it does seem to be fair, given the developer sector has been taken to the brink of collapse, while PBC data show that the trough-to-peak rise in the mortgage rate between 2020 and now was just 30bp.

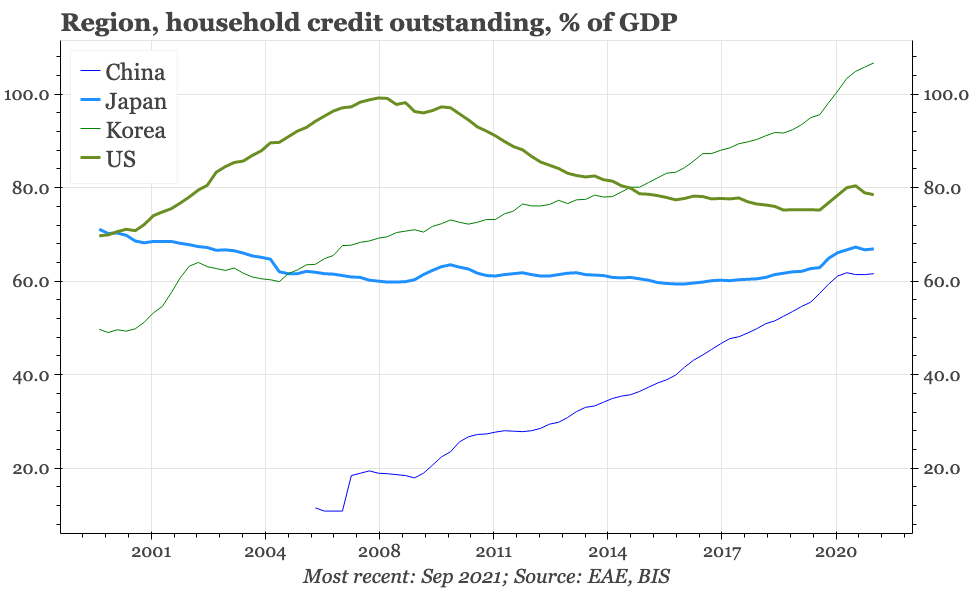

Mortgage rates aren't the only tool available to policymakers wishing to impact home demand. China probably has the largest selection of buyer (and seller) macro-prudential measures of any country in the world. It is also true that there are other important drivers of property demand that shift over time. The growth of urbanisation isn't constant. After all the borrowing of the last few years, household debt in China is no longer low, and debt service payments consequently higher. Intensifying the debt service burden is the slowdown in household income growth, which has been ongoing, but has accelerated after covid.

However, the toolbox of macro-prudential measures has been built up over property tightening cycles going back almost twenty years, with the tools progressively utilised. Indeed, one of the reasons why the focus this time around hasn't been on buyers is because the straightjacket of macro-prudential measures constraining property demand is already so tight. As for debt service payment, these are an issue, but not one that just emerged in the last few months.

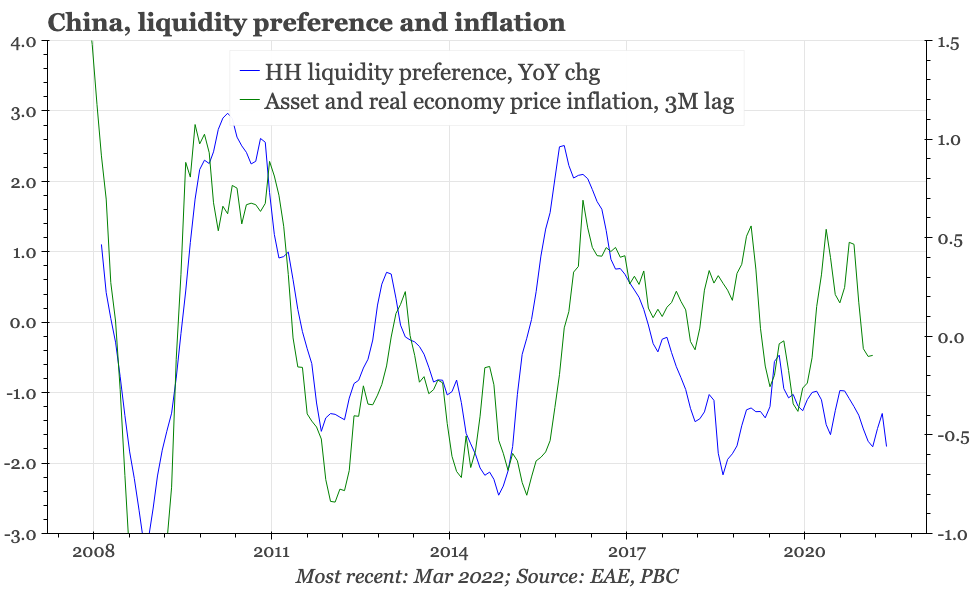

Amid all this noise, it is notable that over a number of cycles key features of demand - in particular mortgage lending and home prices - have tended to follow interest rates. If this wasn't China, that these relationships existed would be quite a natural assumption: in an interest rate sensitive sector like property, demand should be affected by changes in interest rates. When it comes to China, there is a tendency to think that things work differently. It is undoubtedly true that the PBC's traditional focus has been on the quantity of money, not the price. Consistent with that, probably the most popular leading indicator for commentators trying to work out the direction of China's overall economy is the credit impulse. That approach shouldn't be dismissed, but the less-discussed relationship between the credit impulse and interest rates - and in another relevant example, rates and the currency - suggests that for the broader economy, interest rates play a more important role than is usually recognised.

Buyer sentiment as weak as previous cycle lows, but no lower

The role interest rates play in China in general will be a topic for a future note. In the meantime, trying to understand the drivers of the property downturn is important in working out scenarios for how the real estate cycle might develop from here. While at a central government level there hasn't been much change, officials in Beijing have indicated that real estate policy should suit local conditions, and on that basis many regional and city authorities have loosened macro-prudential measures aimed at buyers. Some cities have even started to relax residency requirements needed for property ownership. Cycle considerations aside, this in particular is a welcome structural change, given these restrictions reduce labour mobility.

It is also clear that interest rates are falling. In its attempts to bolster sentiment the PBC has reported that different banks have reduced rates by between 20 and 60bp - so potentially already reversing all the mortgage price tightening of the last couple of years - and there are plenty of reports of the availability of home loans improving. That is consistent with falls in money market rates and bond yields, which also suggest there is more downside for mortgage rates yet.

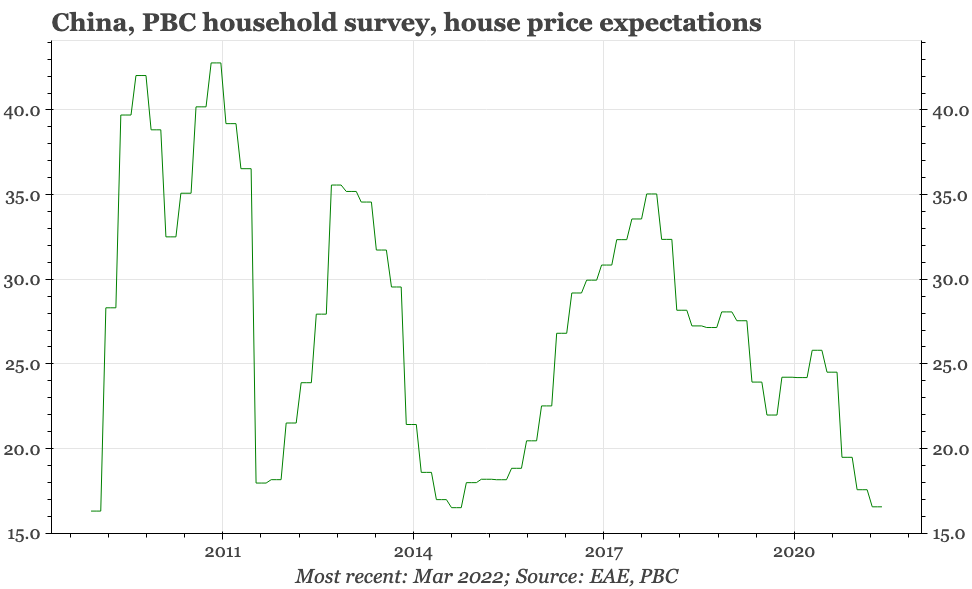

In a usual cycle, these would all be reliable signs that some kind of recovery is in the works. The question then is whether this time is different. It could be, with perhaps the most important issue being whether home buyers believe the three red lines on developer leverage also demarcate the end of the almost two-decade period of ever-rising property prices. If they do, then falling nominal rates don't matter because expectations of lower prices will be raising real rates.

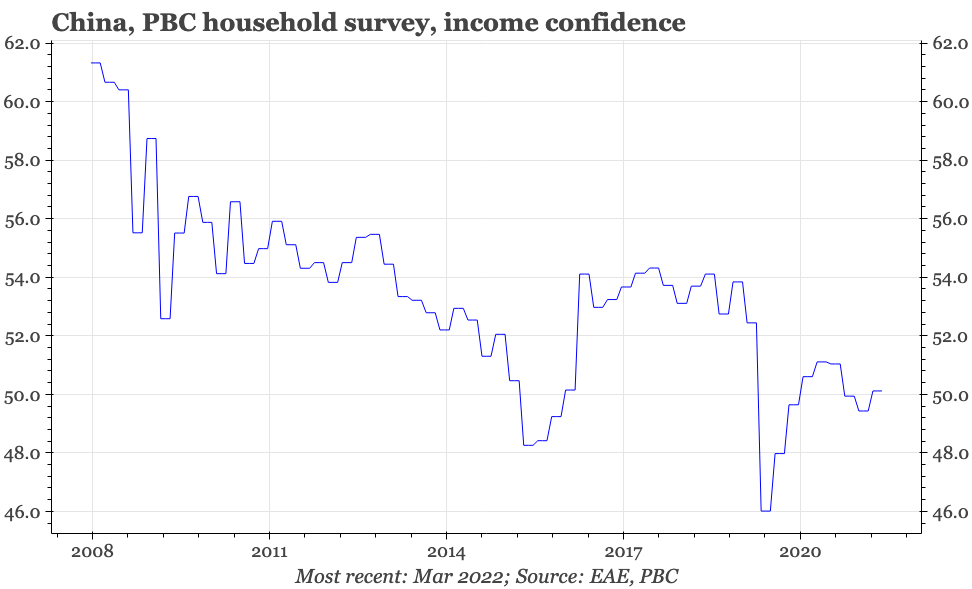

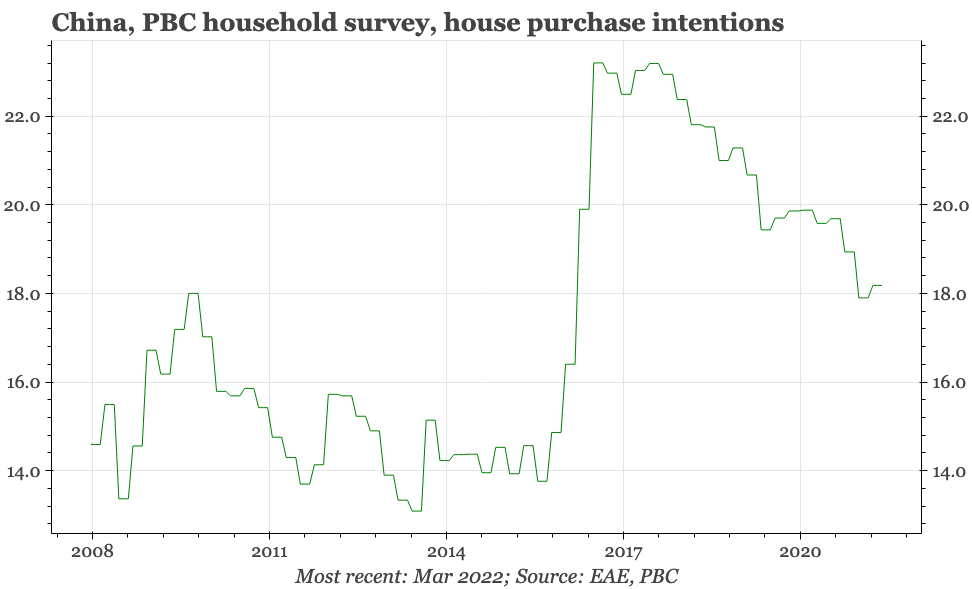

This is certainly a real possibility, but the evidence that this is what has actually happened isn't yet compelling. The longest measures of buyer sentiment available are from the PBC's quarterly depositor surveys, which have a history going back to the early 2000s. These show that price expectations are very soft, but as yet only as weak as previous cycle lows - and on these former occasions, recovery always followed. The survey measure of sentiment towards buying property has weakened, but in level terms remains surprisingly high. In thinking about buyer sentiment, it could be important that the government in March this year pushed back implementation of the long-discussed tax on property ownership. The record of the repeated delays of the last few years meant the latest pledge in October 2021 to push through more pilots of this tax was never particularly credible. From a structural perspective, that is unfortunate, as property taxes would give local governments much-needed new sources of revenue, and would also tackle the long-standing household preference for investing over property over everything else. That said, in terms of the cycle, not implementing the tax is important both substantively and because of the message it sends, that the central government isn't actually discouraging property ownership.

Scenarios for next 6M: property revival or generalised deflation

None of this is to argue with any conviction that the property sector is now about to turn up once again. To be frank, the observations made here about the low level of mortgage rates and the historical relationship between interest costs for buyers and the property market weren't useful guides to the direction of the market in 2021. Despite incremental loosening that began in September last year, the developer sector has remained mired in deep trouble. In the short term it is difficult for property buying to rise if potential purchases aren't allowed out of their homes. More broadly, the covid lockdowns are bad for China's growth in general, while the ongoing zero covid policy will likely mean yet slower growth in household income.

That said, in addition to more policy support for property, the crisis of the last few weeks has also produced a collapse in confidence in what should be the other choices available to households looking to invest - or, if you like, speculate. There isn't strong evidence that the stockmarket and the property market are mutually exclusive investment choices for the Chinese people. As often as not, the two markets tend to move together, with improving sentiment during upturns resulting in a shift of household deposits into more liquid forms that lifts prices in the economy in general. But the recent calamitous performance of the equity market, happening when property prices are at least reported to be holding firm, isn't likely to be encouraging bigger allocations to equities.

It isn't clear - to me at least - where the current consensus is on the outlook for property. There is certainly a lot of pessimism around, and reasonable arguments that the policy shock to the real estate sector has produced an irreversible structural shift down. But there are some establishment economists warning of a rebound in property later this year, and I would agree that this is a risk worth highlighting. The indicators that would suggest that is happening, apart from the obvious ones of rising developer equities and stronger daily property transactions, would be a turn up in buyer sentiment surveys, an increase in mortgage borrowing, and a rise in liquidity preference of households. These indicators are not flashing green yet. But if they do start to, the macro implication would be fairly straightforward, in the sense of signalling a cyclical recovery in the economy.

Given current interest rate settings for property buyers, the consequence of such a recovery not happening would be equally important. Perhaps the population can become pessimistic about prices in the property sector without broader consequences. Probably though, households becoming concerned about falling prices in housing would mean expectations for deflation in the economy more broadly. That would be quite the contrast with the rest of the world, given the current fear of inflation that has become so widespread. It would also mean that while as low as interest rates currently are in China, there would still be room for them to fall further.