The China Diviner

No, it isn't only Hu Xijin who cares about growth. The government does too, albeit these days more because of the debt burden and politics than employment. But policy stimulus is underwhelming, seemingly because of a logjam in thinking: how to get more investment growth, but no more debt.

Is it really only Hu Xijin that cares?

Hu Xijin isn't who many people would be expecting to be taking the lead on Chinese economics. The former editor of the “chest-thumpingly nationalistic tabloid” Global Times, he's perhaps China's best known, often caustic, somewhat official, English-language commentator on Twitter. Domestically, his myriad internet followers are accustomed to a diet of posts criticising and ridiculing the US.

And yet recently, he really has started to talk about the economy. That's not unconnected to his politics, given the Beijing establishment view that China's economy must and will overtake that of the US. But his recent comments have been more about the cycle, and the need for urgency in getting the economy going.

Only using slogans to console the public won't have the effect of stimulating market sentiment. Consumption can only continue to remain strong by making companies good, making employment good, and continuing the trend of rising wages in the whole society.

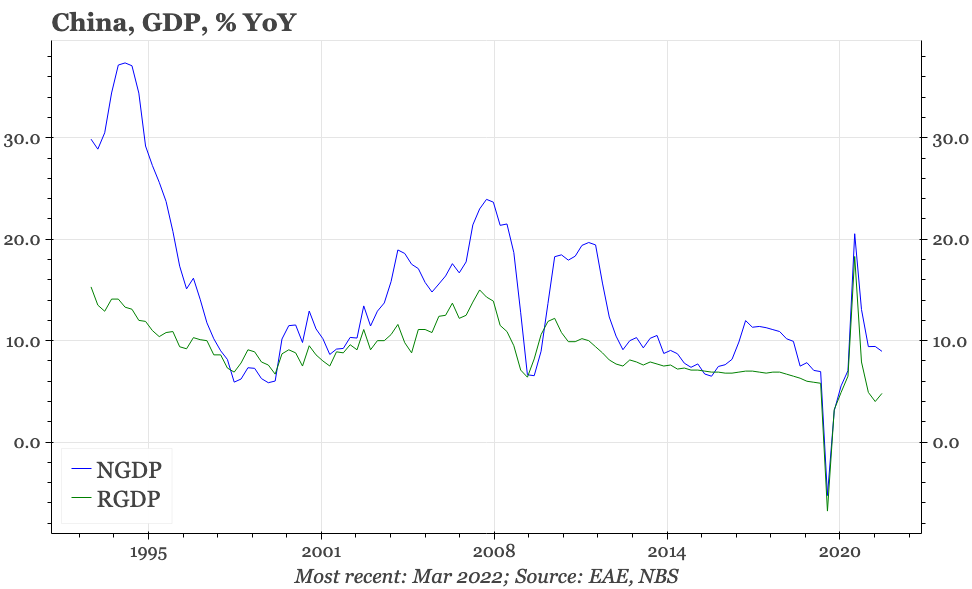

As policy advice goes, this wouldn't be worth noting. Hu Xijin might be sure on the direction, but he doesn't have anything particularly insightful to say how his aims should be achieved. Rather than the content, his remarks matter because of the context. Until Covid-19, China's GDP never contracted. Now GDP might be shrinking YoY for the second time in just two years, and yet there's no great outpouring of demands for stimulus. That at least is the argument of Zhang Mingyang, a blogger who wrote an article, “Apart from Hu Xujin, no one cares about the economy”.

That article won the apparent approval of the head of Tencent, Pony Ma, who recommended Zhang's article to his own followers. Ma was obviously feeling the pain even before this year's Covid-19 lockdowns, with his company's share price falling by more than 50% since February 2021 on the back of Beijing's regulatory squeeze of the tech sector. The difficulty facing entrepreneurs was one of the themes of Zhang's article, as he noted the contradictory demands of netizens: companies “can go bankrupt, but mustn't lay people off; they can go bankrupt, but shouldn't use overtime”.

Zhang also highlighted the lack of intellectuals and indeed economists talking about the economy. One reason is they've been scared off. Zhang highlights the example of one economist, Wu Xiaobo who published an article lamenting the challenges facing companies, and in return was basically lambasted as being a capitalist running dog. This kind of reaction suggests that the Politburo's supposed rediscovery of socialism, an enlightenment that some commentators believe is driving the crackdown on tech, is a trend that enjoys popular support.

Some economists would probably argue this in unfair, and that as a profession, they haven't gone AWOL. As an example, for the last couple of years, former PBC adviser Yu Yongding has been calling for more aggressive cyclical policy. More importantly, the highest ranking economic official in China, premier Li Keqiang, has made no secret of his concern about the current state of the economy. In the official transcript of the “100,000 officials” meeting on May 25th, he was reported as saying that in some respects the economy is worse than in 2020, and that all departments have a responsibility to increase their sense of urgency. In recent weeks the State Council and PBC have been busy announcing new measures to support growth.

However, none of what's been done has felt particularly decisive. That's reflected in the market reaction, with only a modest move up in equities and a moderate steepening of the curve, even as covid restrictions are being relaxed. The market seems to be taking Zhang Mingyang's worries one step further and asking the question: “has even the government stopped caring about the economy?”

Government priorities – changing, not disappearing

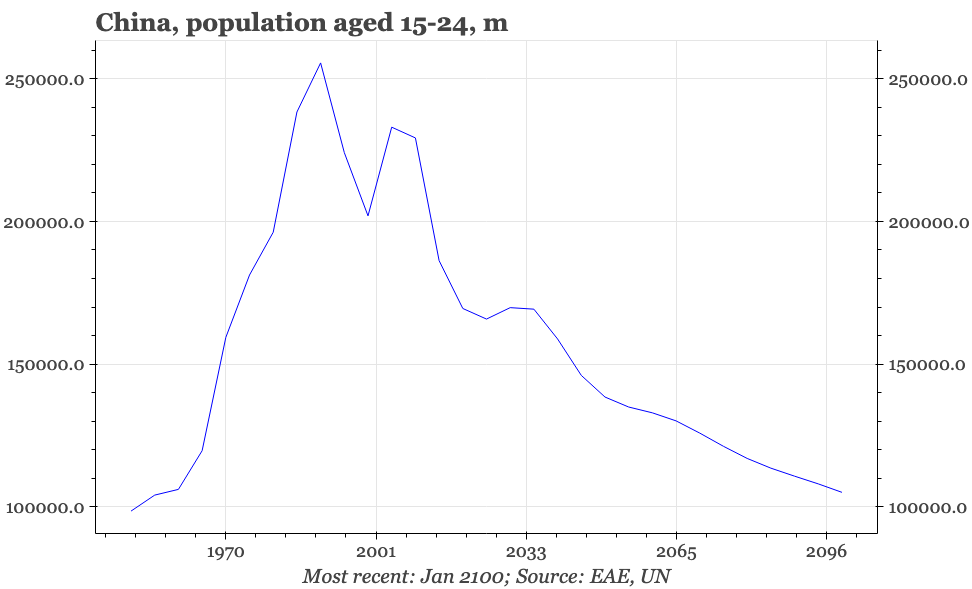

It is certainly true that the authorities don't need growth in the same way they did. In fact, Xi Jinping is the first leader in modern Chinese history – indeed, perhaps the first Chinese leader ever – who doesn't have to worry about overall unemployment as a structural issue. However, while a need to generate jobs isn't quite the ever-present concern it once was, from time to time cyclical unemployment will be a worry. There's also other new economic motivations for maintaining a “reasonable” rate of growth, in particular the high debt burden, even if the concern here is more about nominal than real GDP.

In addition, the current leadership, as its predecessors had done, has made achievement of economic development a key part of the Chinese Communist Party's ruling agenda. Li Keqiang has argued that “development is the basis and essence of resolving all the country's problems”. Xi meanwhile has suggested that GDP can double by 2035, a change which the central committee says would raise living standards, drive a “sharp rise” in the country's overall strength – and although left unspoken by the top leaders in their public remarks, allow China to overtake the US.

This isn't to argue that there is no change in the way the current leadership views economic growth. Doubling aggregate GDP in the next 15 years implies average annual growth of a little under 5%. That's still very ambitious, but is nonetheless a rather slower trajectory than the average of over 8% in 2005-20. And Xi's administration has attached a lot of importance to China “transitioning from a phase of rapid growth to a stage of high-quality development”. As early as his 2017 speech at the 19th five-yearly congress of the CCP, Xi made clear that this vision included the achievement of “common prosperity”, though this particular slogan only became a big issue for the financial markets when it became associated with last year's tech crackdown. That regulatory attack, of course, doesn't look pro-growth. But Xi himself said common prosperity could only be achieved via continued “development”, and all officials explanations that try to flesh out this slogan stress that “growing the cake” has to come before “dividing the cake”.

Anyway, given the CCP's over-arching plan for the “rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”, it seems unlikely top leaders have suddenly given up on growth. But if that's right, then how to explain Hu Xijin's apparent loneliness in discussing the economy, or the lack of oomph in this year's post-lockdown loosening policies? Probably, the hold-up is an issue discussed in the China Diviner before: on the one hand, officials are fixated on the idea that policy stimulus can only be delivered via the old economy route of investment and corporates, but on the other they worry that this sort of stimulus will entail a new step-up in China's macro leverage ratio. Until this intellectual gridlock can be cleared, policy will likely continue to feel underwhelming.

Employment – creating 2m jobs a year

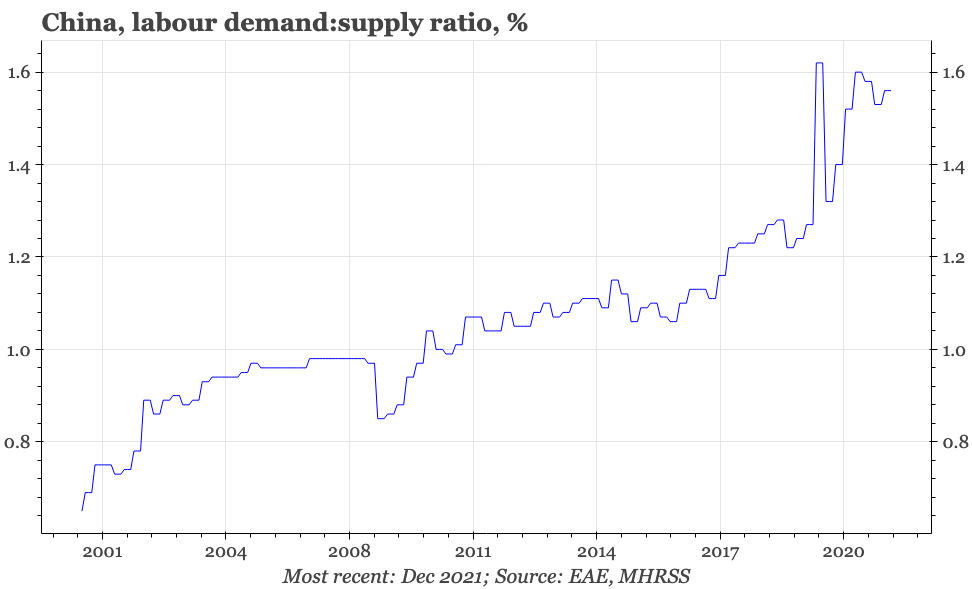

That China needs growth to create employment has been a basic assumption in understanding Beijing's policies towards the economy ever since reform and opening started in 1978. But that assumption is becoming less valid, for the simple reason that employment today isn't the pressing issue it once was. The huge expansion of the economy of the last forty years, together with the recent sharp fall in new entrants to the workforce on the back of the one-child policy, has exhausted what was once a structural over-supply of workers in the countryside. That can be seen in official data, which show a multi-year rise in the demand:supply ratio of workers in cities. That the structural over-supply of underemployed workers in rural China has now been used up is perhaps even more persuasively illustrated by an anecdote from rural development expert Scott Rozelle:

Whenever I bring students....to rural China for the first time, I ask the same question. I pull out a hundred-yuan bill from my pocket and hold it up. “You see this?” I say, looking around theatrically. “Whoever can find a working-age man in this village gets one hundred yuan. He has to be between eighteen and forty, and has to be healthy”. Everyone laughs, thinking one of them is about to make some easy money. But every time, as we go around the village, no young men appear. By day's end, I always win my bet”.

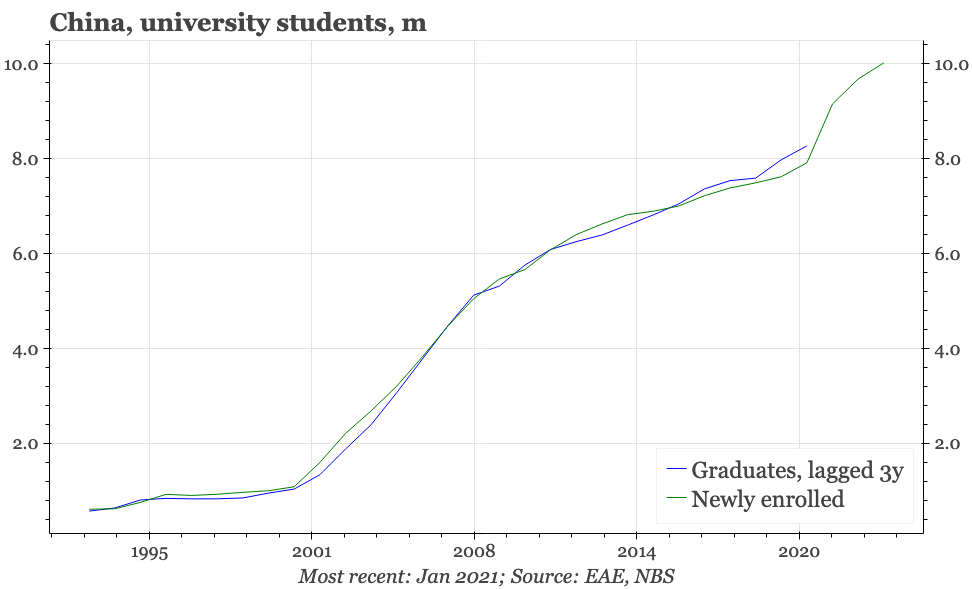

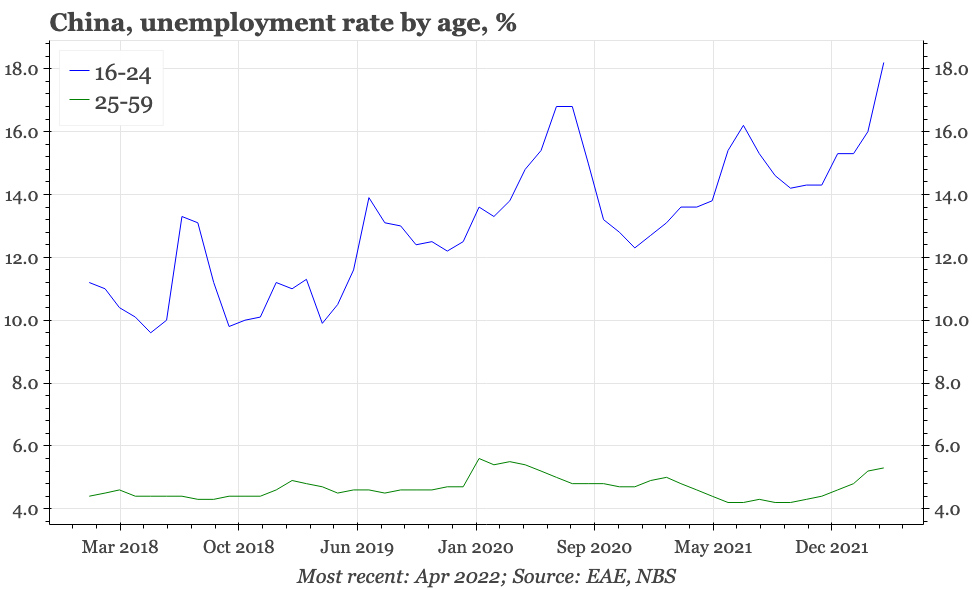

This fact that almost all young men have left the countryside to work in the cities doesn't mean employment isn't a policy concern at all. If economic activity stops – which happened when domestic and external slowdowns coalesced in 2008, or during the covid lockdowns of Wuhan and more recently Shanghai – the government has and will become more concerned about employment. And even if the economy was roaring ahead this year and overall joblessness was low, officials would likely still be worried about sectoral unemployment. In particular, generating jobs for graduates has been a worry for years. It is a concern that will intensify as a result of the latest step-up in college enrolment that began in 2018, which will increase the number of graduates by around 2m/year.

Still, these are different worries from those that faced Chinese leaders during the first thirty years of economic reform. Back then, there was clearly a structural deficiency of jobs. In that situation, creating sufficient employment was the over-riding economic goal of the government, a priority which informed the policy of sustaining rapid rates of GDP growth. Now the employment challenge is much more cyclical.

Debt – the importance of nominal GDP

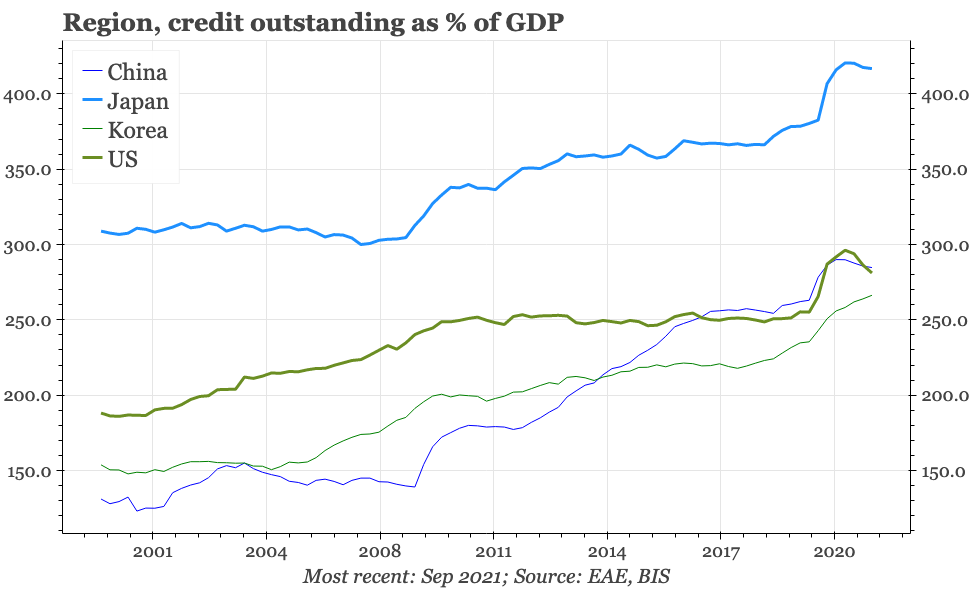

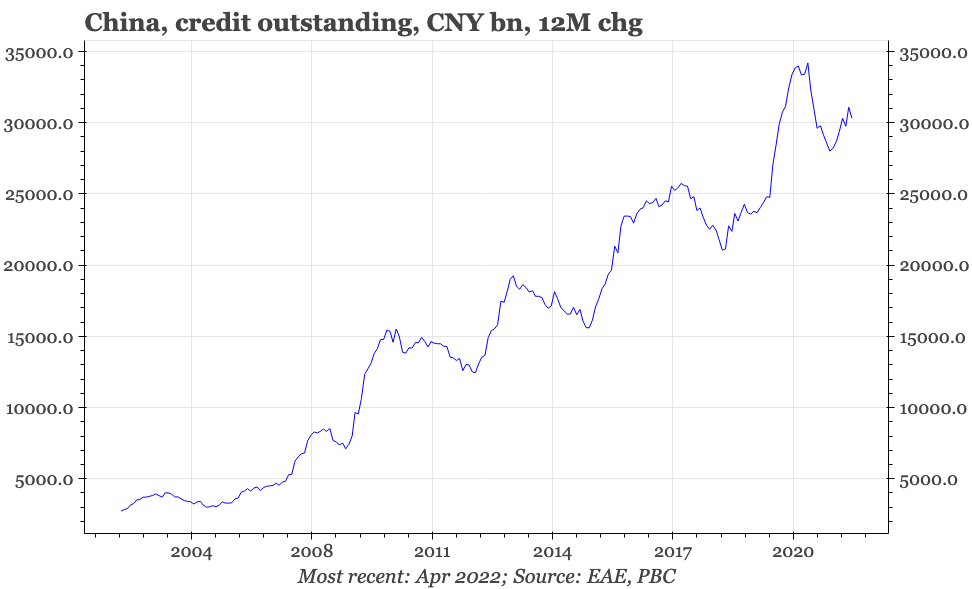

Again, this change in the underlying employment situation is because of both supply and demand. Changing demographics have made a big difference, but so has the growth in the sheer size of the economy, with GDP more than tripling just since 2008. The massive expansion of the economy since the global financial crisis has been accompanied by a big increase in debt. As that has happened and the employment challenge has become less challenging, so managing the debt burden has become an important new consideration in shaping the government's attitude towards economic growth.

The up-cycle in the economy that began in 2015 was a good illustration of this shift. In the years just before then, real economic growth has slowed from a bit under 11% to 7.4%. Despite that slowdown, unemployment didn't look to be becoming particularly troublesome: the slight fall in the demand:supply ratio of workers was nothing like the collapse in 2008. But nominal GDP growth decelerated quickly, from almost 20% in 2011 to under 8%.

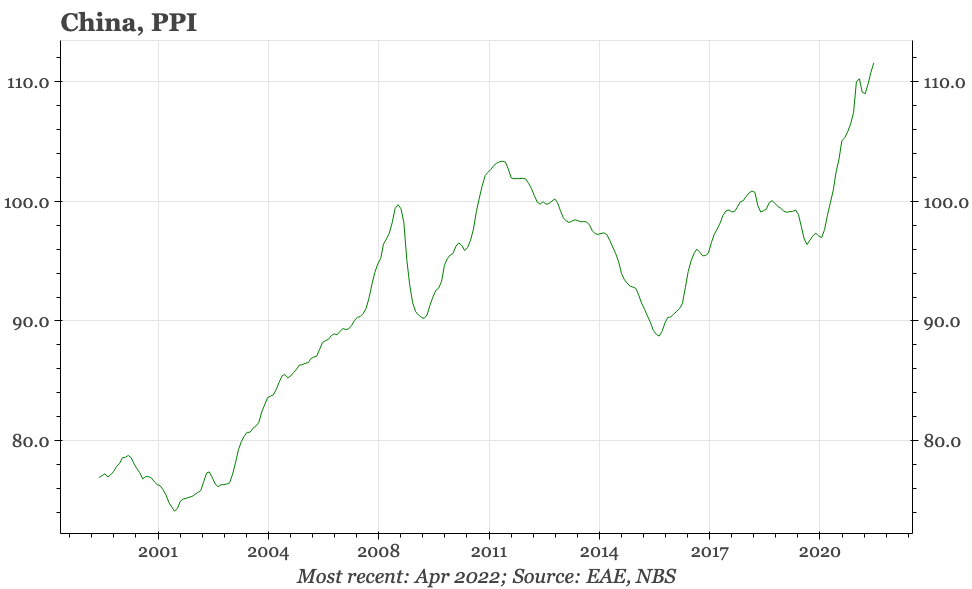

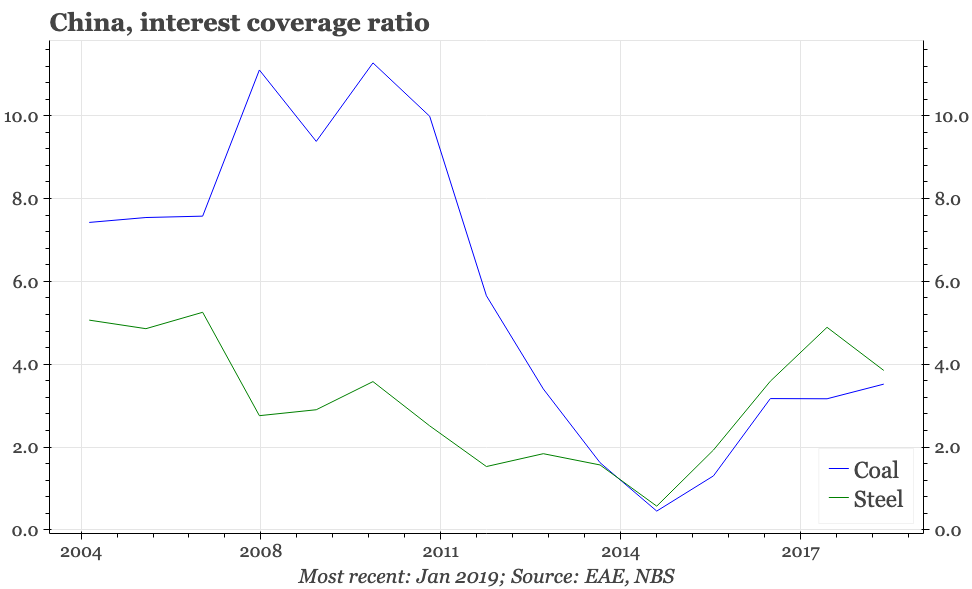

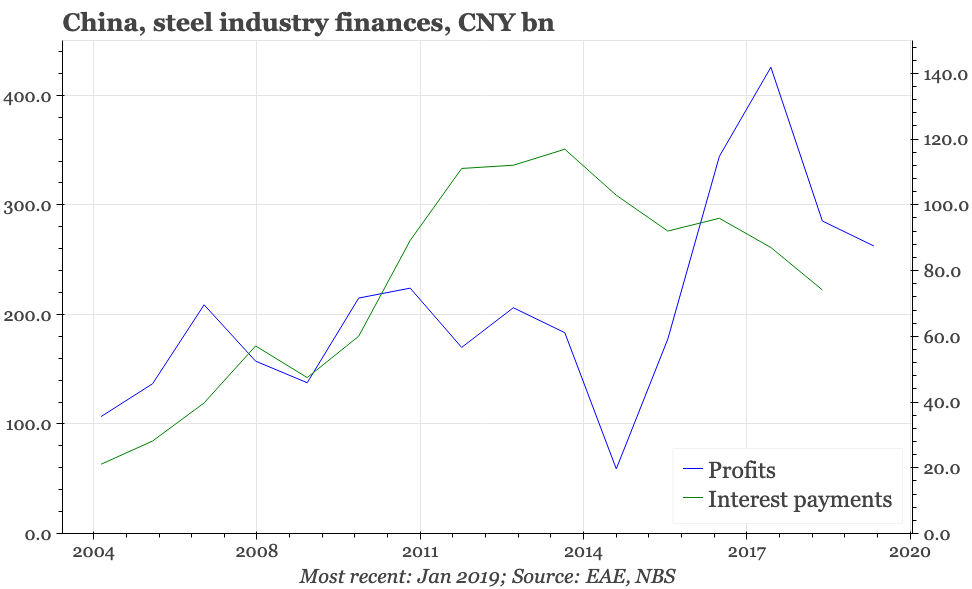

This was because the slowdown in real GDP economic was accompanied by a weakening of commodity prices, with PPI inflation in China falling YoY every month from early 2012. That was terrible for the profitability of mining and commodity-processing sectors. They in turn mattered for the economy. These sectors are big: in 2015, coal mining and steel production alone accounted for more than 10% of total industrial revenue. In addition, they were some of the biggest borrowers after 2008, so falling output prices threatened their ability to repay debt. With nominal GDP growth the denominator in the calculation of the debt:GDP ratio, this fall in prices also made containing the rise in debt even more difficult.

Faced with this situation, the government's solution was to stimulate demand, with a renewed loosening of fiscal and monetary policies. At the same time, officials started to push supply-side reform, the idea being to reduce excess capacity in the heavy industrial sectors, and so push up prices and profitability for the firms that remained. At the end of 2015 the State Council set targets of reducing capacity in steel and coal by 45 m tons and 250 m tons receptively within a year (State Council 2016a and 2016b). In addition, the government laid out plans for even bigger capacity reductions in these industries in the medium term.

There is room to debate the relative importance of the macro boost to demand and the micro reduction in supply, but it is clear now that 2015 marked the low for commodity prices. Even before Covid-19, PPI in China had rebounded by a cumulative 11% – and in the two years since the pandemic started, it has risen a further 12%. As that has happened, the profitability of heavy industry has also lifted, as has the GDP deflator, with a clear gap once again opening up between real and nominal GDP.

To be sure, raising the denominator isn't the only way China has tried to control leverage. There's also been direct efforts to slow down and reduce borrowing in different sectors, with the latest target being property developers. It is also true that despite all the efforts made by policymakers to control leverage, China's debt to GDP ratio is considerably higher now than it was in 2015.

That is important, but it doesn't negate the significance of the policies of that year. The rise in debt is partly the result of the economic disruption caused by the pandemic: between 2017 and 2020 the debt:GDP ratio had finally stabilised. And the fact that the debt:GDP ratio has now stepped up again means that the authorities' reaction function of 2015 remains relevant today. Along with maintaining something close to employment, it seems reasonable to assume that sustaining a positive rate of PPI inflation and so holding up nominal GDP growth is a key economic policy aim of the government.

Politics – overtaking the US

In 2017, at the last five-yearly congress of the Chinese Communist Party, Xi Jinping laid out a two-stage plan of development for China between 2020 and 2050. This would entail achieving “socialist modernization” by 2035, and over the next fifteen years developing China into a “great modern socialist country that is prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced, harmonious, and beautiful”. That's a ground-sounding statement, but also fairly vague. Even then, though, economic development was clearly a critical part of the plan, with the first definition of socialist modernization being that by 2035 China's “economic and technological strength” would have “increased significantly”.

When more detail was added by the fifth plenum of the CCP's central committee in 2020, the importance of economic development became clearer. The statement released at that meeting pledged that by 2035, China's per capita GDP would reach the level of a “moderately developed country”. That still isn't particularly explicit because a “moderately developed country” isn't a standard international term. But in a speech published to explain these plans, Xi Jinping said it is “entirely possible” for China's GDP to double by 2035. His speech didn't lay that out as an absolute goal, but it does seem to capture the essence of government thinking.

Xi's over-arching aim is “realizing the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”. It is highly likely that this entails China's economy overtaking that of the US to become the largest in the world. Top leaders don't tend to spell that out, but it is clear from remarks made by establishment economists. As an illustration, these are comments made earlier this year by the CAA economist Li Yang:

The reason the US names China as the main competitor is because one day the scale of China's economy will undoubtedly overtake that of the US. If we want to overtake the US, then from now until quite some time in the future, our economic growth must be clearly higher than that of the US.....in addition, fundamentally, the superiority of the socialist system is mainly reflected in our ability to produce a higher growth rate than capitalist economies, and produce a higher rate of productivity.

Waiting for macro policy clarity

It is possible that the government has given up, and that plan is to keep the borders closed and somehow muddle through with low rates of growth. But that seems very unlikely. The government will be concerned that cyclical unemployment, particularly among students, can develop social unrest. Low rates of GDP growth, particularly in nominal terms, would result in a further spiralling upwards of the debt:GDP ratio – Li Yang, the CASS economist, is already warning that China is at risk of entering a Japanese-style balance sheet recession. And a further expansion of the economy is a key component of the CCP securing its “rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”.

However, wanting growth is one thing, achieving it is quite another. I am sceptical about the current negativity on the long-term outlook for China. But in the short-term, policy does seem to lack direction, with one likely explanation being policymakers are stuck between their long-standing commitment to investment spending as the main driver of growth, and their more recent reluctance to allow yet another rise in debt. As long as the current covid lockdowns end, activity will recover. However, for recovery to exceed current market expectations, this logjam in policy thinking likely needs to be resolved.